Human-like robots that stride around on two legs have long been the stuff of science fiction movies and research labs. Now they just might be coming to work in a warehouse near you.

You’ve probably heard of robots in warehouses, but this is different. With their metallic arms and legs, these machines can fetch and carry objects much like a human. They’ll start out by moving boxes of merchandise onto conveyor belts, but their descendants could one day restock supermarket shelves or lug packages from delivery trucks to our front doors.

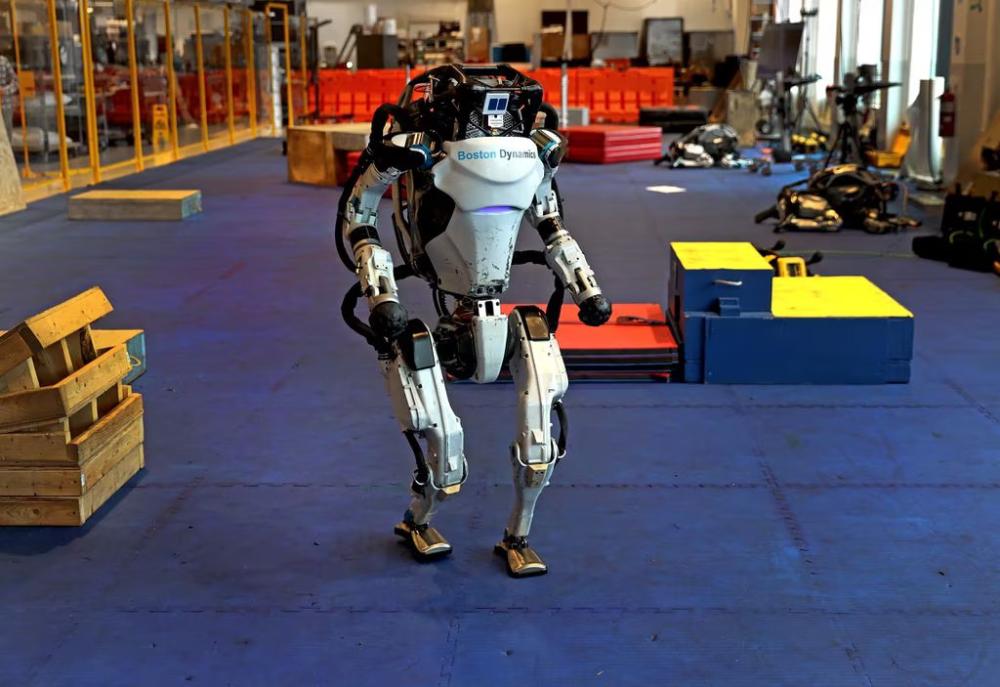

It sounds like the latest advance for a Boston-area warehouse automation company, or perhaps Waltham’s Boston Dynamics, which is famous for videos of its breakdancing Atlas humanoid robots. But it’s not. These robots come from companies you’ve likely never heard of.

Agility Robotics, for instance. This startup in Corvallis, Ore., is so confident in the success of its two-legged robot, called Digit, that it’s building a factory capable of making up to 10,000 of them per year. Agility announced last week that it expects to begin production later this year. The company has raised $179 million from investors including retailing titan Amazon, which runs its own warehouse robot operations out of North Reading and Westborough.

Agility has plenty of other competition. In Austin, Texas, a company called Apptronik has raised $28 million to develop a humanoid warehouse robot called Apollo which will begin field tests next year. California-based Figure and the Canadian company Sanctuary AI are also getting into the game. Even electric carmaker Tesla has been showing off prototypes of a humanoid robot.

Until now, the cost and technical challenges of building humanlike robots have precluded their use in business. There’s also the risk of putting such machines to work in close proximity to humans who might be injured if a robot malfunctions. But the new wave of robot makers say they’ve created humanoid machines that are ready to get to work.

For now, Boston Dynamics remains on the sidelines, even though the company, owned by South Korean conglomerate Hyundai, has developed walking robots for more than three decades. The company has been selling Spot, its doglike four-legged robot, since 2020 but has never marketed a commercial version of the two-legged Atlas. Asked whether this might soon change, the company replied with an emailed statement.

“Our work with Atlas remains focused on near-term research and development motivated by and in support of launching commercial products,” the statement said. “Pushing the limits on a humanoid like Atlas drives hardware and software innovation that translates to our other robot platforms. It also helps us explore the art of the possible as we think about the capabilities and applications future robots will need.”

A Boston Dynamics spokesperson added that Atlas engineers are “starting to explore capabilities like two-handed mobile manipulation and applications that look closer to something you might find on a real-world job site.”

Jonathan Hurst, Agility Robotics’ cofounder, studied mechanical engineering at Carnegie Mellon University and was a summer intern at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Hurst agrees that Boston Dynamics is a pioneer in humanoid robotics. “I’ve known them for a long time,” he said. “We have a good relationship as competitors, but friendly competitors.”

The issue with Boston Dynamics’ humanoid robot, Hurst said, is that it’s too powerful. Atlas uses high-pressure hydraulic fluid, enabling its quick and powerful movements. But “there is no path to make that efficient,” Hurst said, because hydraulic systems are heavy and consume lots of battery power.

Boston Dynamics is world-famous for videos of its breakdancing Atlas humanoid robots.David L. Ryan/Globe Staff

They’re also potentially dangerous. A fluid leak could injure nearby workers and contaminate the workspace. And the robot’s powerful arms and legs could easily smash anybody who gets in the way. “They’re never going to be safe to put around people,” said Jeff Cardenas, Apptronik’s chief executive and cofounder.

Apollo, Digit, and other walking robots rely on electric motors, making them lighter and more energy-efficient than Atlas. They can’t perform backflips, but Cardenas said that in real-world applications “you don’t need to do parkour.”

The robots also move more slowly than Atlas, making them safer around humans, and their electric motors can stop them instantly if the robots bump into something.

There are also substantial differences between Digit and Apollo. For instance, Digit claims a two-hour battery life, while Apollo expects four hours in normal use. The Apollo battery can be swapped out by a human worker, while a depleted Digit will walk to a battery charger and plug itself in for an hour.

The Apollo weighs 160 pounds and can lift up to 55 pounds, while Digit weighs in at 141 pounds and has a 35-pound lifting capacity.

Cardenas said that when the Apollo enters full production in early 2025, it’ll be “roughly the price of the average car.” Hurst said his company’s Digit machines will go on sale early next year; he said a prototype created for preproduction testing cost $250,000, but the commercial version will cost considerably less. Both companies say they’ve lined up customers but won’t identify them yet.

The usual question arises: Won’t these robots displace human workers?

The usual answer: Not likely, say the robot makers. Warehouses find it difficult to recruit enough workers, because the jobs tend to be strenuous and dull. Cardenas said that robots may reduce worker turnover by allowing humans to handle the easier tasks. Meanwhile, “robots can take over the part of the work that people don’t like doing,” Cardenas said.

These robots likely will first see action in warehouses, where they’ll grab plastic boxes filled with merchandise, then carry them to a conveyor belt a few steps away. The robots will be physically isolated from human workers, to minimize any risk of accident. However, the machines are designed to function safely even when people are nearby. For instance, they’ll walk around obstacles rather than run into them.

Because warehouse floors are flat, putting such a robot on wheels would be just as effective, and cheaper. But like teenagers working in a warehouse, this is a starter job, meant to prove the machines’ reliability, while generating revenue for the robot companies.

“We’re starting in the warehouse because that’s the most structured of the environments,” Cardenas said.

Ron Kyslinger, an independent consultant who has worked on robot deployments at Amazon and Walmart, is skeptical about walking warehouse robots. “Their application isn’t extremely practical right now,” he said. Moving relatively lightweight plastic bins is a dull job, but “a human can do this pretty much all day long.”

Kyslinger said what’s needed are humanoid robots that can bend over and lift heavy loads — the sort of effort that often causes back injuries in humans. “I’d be more impressed if it was picking up 40- or 50-pound bags of dog food,” he said.

But the robot makers say their legged robots are being given the easy jobs first, while being groomed for tasks where wheels won’t work, like climbing stairs or stepping over curbs. In time, the machines will be trusted to work outside the warehouse. They could handle tasks like stocking store shelves or delivering packages to homes. Hurst foresees a future in which autonomous delivery trucks pull up to the curb to wait, while several autonomous robots climb out, select the correct parcels, and carry them to our front doors.

If it all comes together — still a huge “if” — Apptronik, Agility, and other humanoid robot makers could spawn a vast new global market, one that Boston Dynamics might still tap. The company has been late to the party before. Last year, long after other local companies helped spawn a warehouse robot boom, Boston Dynamics introduced Stretch, an automaton built to unload trucks. If two-legged robots catch on, Boston Dynamics may once again decide to catch up.

Hiawatha Bray can be reached at hiawatha.bray@globe.com. Follow him @GlobeTechLab.

Spread the word