Forward Ever: 40 Years On From the End of the Revolution and the U.S. Invasion of Grenada

Dear Comrades

if it must be

you speak no more with me

nor smile no more with me

nor march no more with me

then let me take

a patience and a calm

for even now the greener leaf explodes

sun brightens stone

and all the river burns.

Now from the mourning vanguard moving on

dear Comrades I salute you and I say

Death will not find us thinking that we die.

—Martin Carter

With this poem, George Lamming, Barbadian novelist and poet, ended his address at a December 1983 memorial service in Trinidad for Maurice Bishop, Jacqueline Creft, Norris Bain, Vincent Noel, Unison Whiteman, and all who had been killed during the abrupt end to the Grenada Revolution.

“It is the tragedy of a whole region which has brought us here,” said Lamming during his address. “The landscape of Grenada and its people are the immediate victims… But all of us are now the casualties of the American invasion.”

When an intra-party conflict broke out, leading to the killing of revolutionary leader Bishop and other victims on October 19, 1983, the Reagan administration seized the pretext to invade. On October 25, 1983, thousands of U.S. troops landed on the island.

This year, Grenada commemorates both 50 years as an independent nation and 40 years since the violent implosion of the People’s Revolutionary Government and subsequent U.S. invasion. For the first time, the government of Grenada has recognized October 19 as a national holiday, designated as “National Heroes Day.” Decades on, reckoning with the events of 1983 continues.

Writer Marise La Grenade-Lashley spoke at the inaugural National Heroes Day gathering, where she echoed sentiments expressed in her article in Now Grenada a year prior. “The shocking events of 19 October 1983, whose effects reverberated across the Caribbean and beyond, created deep psychological wounds that have never really healed. One coping mechanism adopted by some persons directly affected by the events of that fateful day has been to retreat in silence,” she wrote.

“While silence is a common reaction to trauma, it has, in the case of Grenada, created a void in our society that needs to be filled with factual and unbiased information related to those four and a half years during which Grenada embarked on an alternative path to development that crumbled so abruptly, so brutally, so tragically,” La Grenade-Lashley added.

The designation of National Heroes Day includes a mandate to bring the history of Grenada’s revolution to civics classes in Grenadian schools.

A Revolutionary Movement Provokes U.S. Ire

In 1979, Maurice Bishop and his New Jewel Movement (NJM) took control from the increasingly authoritarian regime of Sir Eric Gairy, Grenada’s first prime minister. Gairy, an ally of Chilean dictator General Augusto Pinochet and creator of the notorious “Mongoose Gang” private militia, modelled after the Haitian Tonton Macoutes, had lost public support and remained in power through rigged elections.

The insurrection installed the NJM as the People’s Revolutionary Government (PRG), suspended the 1974 Constitution, and declared Bishop prime minister. The government’s first steps were to encourage trade union representation, introduce free medical services, and to prioritize education and adult literacy programs as well as projects benefitting small farmers and farmworkers.

One month into the PRG’s rule, Bishop gave a national broadcast after a visit from U.S. Ambassador Frank Ortiz. “The ambassador pointed out that his country was the richest, freest, and most generous country in the world, but as he put it, ‘We have two sides,’” said Bishop. “We understood that to mean that the other side he was referring to was the side which stamped on freedom and democracy when the American government felt that their interests were being threatened.”

Over the next four years, Bishop spoke often of the U.S. pressure on the PRG. He felt that the Reagan administration was seeking to destabilize the revolution through the media and through economic trade disruptions. The Monroe Doctrine had given way to the Reagan Doctrine, and closer Cold War ties from Grenada to Cuba and the USSR could not be tolerated. As Hugh O’Shaughnessy, a British journalist who was on the ground in Grenada when the invasion finally happened, put it: “The State Department and the Pentagon in Washington…had been seeking ways of putting an end to the left-wing government of Grenada.”

Meanwhile, the PRG was putting in place a variety of projects, one of which was a program—the National Cooperative Development Agency (NACDA)—to deal with the joblessness and landlessness faced by the country’s youth. Trinidadian-born Regina Dumas moved to Grenada in March 1980 to take up a role as registrar of cooperatives within NACDA. “It was like all my dreams had come true,” Dumas said when we spoke on October 17, a few days before the National Heroes Day celebrations. “Here I am, working with rural people, farmers, and listening to them talk, and realizing—these people know what they want.”

In her book, Memoir of a Cocoa Farmer’s Daughter, Dumas describes her work at NACDA, which involved helping to get privately held, uncultivated land into the hands of young prospective farmers tasked with reviving the local and export agriculture markets.

In those days, Dumas often took Sunday afternoon drives to visit the construction site of the new international airport. Supported by Cuba and other countries, the airport was one of the PRG’s flagship projects. “That the government of Cuba chose to support this initiative by providing a skilled work force…was the cause of much rancour with the United States which stridently opposed it,” Dumas writes in her memoir.

During a nationally televised address in March 1983, Reagan displayed a picture of the airport runway under construction. “The Cubans with Soviet financing and backing are in the process of building an airfield with a 10,000-foot runway,” he said. “Grenada doesn’t even have an air force. Who is it intended for?” The implication was clear. During the invasion later that year, the airport would be one of the locations bombed by the U.S. military.

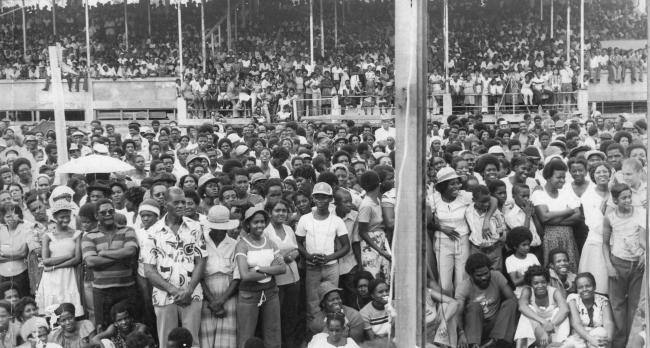

People gather for a packed rally during the Revolution, March 1979. (Grenada National Museum)

The Revolutionary Government Implodes

Months away from the Revolution’s fifth anniversary, divisions within the PRG between Bishop and his deputy prime minister, Bernard Coard, began to come to a head. “Why, when they knew that the Reagan administration was poised to pounce at the slightest error made, would they play into their hands so easily?” said Dumas. “I dismissed, completely out of hand, the rumors that I heard as counter-revolutionary propaganda. What an error on my part!”

The rumors were becoming reality. Disagreements between Bishop and Coard over a plan for shared leadership turned sour, and Bishop was deposed and placed under house arrest in the first week of October 1983. On October 19, six days after Bishop had been placed under house arrest, Dumas recalls hearing the chanting of hundreds of Grenadians marching the streets in support of Bishop. “The plan, apparently, was to march to the residence of Maurice Bishop, where he was being held, confront the members of the People’s Revolutionary Army (PRA), who were holding him hostage, and forcibly, if necessary, free him from his temporary prison and reinstate him as prime minister,” she said.

After gathering her two children from school and returning home, Dumas watched in horror from her veranda as the march, which had successfully liberated Bishop, went to Fort Rupert (originally called Fort George, but renamed after Bishop’s father Rupert, who had been killed by Gairy’s Mongoose Gang in 1974). Once at Fort Rupert, they were faced with a hail of bullets. “Armored personnel carriers began to shoot directly into the crowd of people who were climbing the fort, singing and dancing with Maurice on their shoulders,” Dumas writes in her book. “With no other point of exit…I watched as people leaped over the edge of that fort, quite substantial in height, and into the crashing waves and rocks below.”

Within hours, Bishop had been executed alongside 10 others at Fort Rupert. General Hudson Austin issued a national announcement: “With immediate effect, and until further notice, anyone caught on the streets of St. George’s and environs will be shot on sight.”

The Invasion Strikes

For Dumas, the events were both political and personal. “They had killed the prime minister of the country and others of their own group and party. They had killed my friend Jacqui, thus leaving her young son an orphan,” she said. “They had decidedly opened up the gates to those who had always opposed the revolution.”

President Reagan ordered troops to invade Grenada on October 25. As O’Shaughnessy wrote: “At 6:40 on the morning on Thursday 27 October 1983 a platoon of U.S. marines edged nervously past the main branch of Barclay’s Bank in St. George’s, the capital of Grenada, towards Fort Rupert. They need not have worried. No resistance awaited them there.”

The arrival of the U.S. military brought a rain of bombings across the forts and levelled a mental health hospital, killing 30 patients and wounding many more.

Neville Warner, a Tobago-born son of a Grenadian family, recalls to me how the PRG had built a factory in St. George’s to begin producing mango nectar on a large scale for local consumption and export, as part of the government’s push to localize food production and reduce dependence on imports. The factory was one of the locations bombed as the U.S. troops landed. The space where it stood now hosts a factory producing Coca-Cola.

During the invasion, Cubans were rounded up from the Cuban Embassy and sent back to their homeland. In November, Fidel Castro would pay tribute to the Cubans killed in Grenada during the destruction of the airport. “The U.S. government looked down on Grenada and hated Bishop. It wanted to destroy Grenada’s process and obliterate its example. It had even prepared military plans for invading the island—as Bishop had charged nearly two years ago—but it lacked pretext,” Castro said in a speech in Havana. He lauded Grenada’s social and economic advances despite the U.S. hostility.

“Bishop was not an extremist,” Castro continued. “Rather, he was a true revolutionary—conscientious and honest…Grenada had become a true symbol of independence and progress in the Caribbean.”

The events that unfolded in Grenada would echo throughout the Caribbean and the world. With a quick military victory secured, the emboldened Reagan administration doubled down on counterinsurgency in Central America, supporting ruthless regimes in Guatemala and El Salvador and backing the Contras in Nicaragua. Six years after landing in Grenada, U.S. troops invaded Panama.

For La Grenade-Lashley, there’s more to be done in the work of remembering 1983 and the Revolution that preceded it. “Rather than lament the irretrievable, we can look to the future with optimism,” she writes. “To teach and enlighten our youth, accurate and unbiased information can be culled from the many books, articles and papers written on the Grenada Revolution.”

“We have heard of Truth and Reconciliation Commissions around the world,” she continues. “In Grenada, although we have had our own Truth and Reconciliation Commission, it remains vital that we pay closer attention to the ordering of these three words. Truth and reconciliation. Truth precedes reconciliation.”

Editor's note: This article was corrected on November 8, 2023 to remove inaccurate references to "Bloody Sunday."

Amy Li Baksh is a Caribbean writer, artist, and activist based in Trinidad and Tobago. Their academic background is in Caribbean history and literature with a particular interest in postcolonial social movements across the region.

The North American Congress on Latin America (NACLA) is an independent, nonprofit organization founded in 1966 to examine and critique U.S. imperialism and political, economic, and military intervention in the Western hemisphere. In an evolving political and media landscape, we continue to work toward a world in which the nations and peoples of Latin America and the Caribbean are free from oppression, injustice, and economic and political subordination.

For more than 50 years, NACLA has been a leading source of English-language research and analysis on Latin America and the Caribbean. Our mission has always been to publish historically and politically informed research and analysis on the region and its complex and changing relationships with the United States. We use the NACLA Report on the Americas, our web platform nacla.org, as well as public events and programming as tools for education, advocacy, dialogue, and solidarity. Our work aims to assist readers in interpreting the most pressing issues in Latin America and the Caribbean, and their connections with U.S. policy, to help further movement struggles throughout the hemisphere.

Our mission is guided by our organizational values. NACLA offers a forum for debate among a range of voices and perspectives on the Left. As we enter our sixth decade, we maintain an editorial focus on issues related to political economy, race and indigeneity, gender/sexuality, and climate and the environment. NACLA also provides a platform for voices from the region, and has made a commitment to emphasize Black, Indigenous, Latinx, LGBTQI+, and feminist perspectives.

For more about NACLA and our work, read our history.

We’re proud of the work we’ve accomplished this year with the support and partnership of NACLA readers, supporters, contributors, and staff. Now, we’re raising $30,000 to continue working toward our mission in the new year. With your support, we’ll be ready to charge ahead with our plans for 2024. Thank you for supporting NACLA!

Spread the word