Tens of millions of workers in the United States want a union at their workplace, but do not have one. This unfortunate state of affairs is normally blamed on external obstacles such as our country’s broken labor law regime. But there are also significant internal obstacles within the labor movement that prevent it from scaling up to meet the widespread demand for workplace representation.

Unions frequently refuse to lend support to workers who reach out for organizing help in part because labor’s predominant unionization approach is so staff-intensive and expensive—costing up to $3,000 for every new worker organized and generally requiring one staffer for every 100 targeted workers. Instead, they generally only take on workers who are in a big enough workplace to justify the cost of winning and servicing a contract, who are in a locale where the union already has an institutional base, and who have agreed from the outset to unionize, not just fight for immediate demands.

The deeper problem is that labor does so little to proactively reach out to and support the countless people who could initiate organizing campaigns on their own if given the proper encouragement and training tools. With most unions refusing to use their coffers to widely encourage such worker-initiated drives—and to turn those that catch on into ambitious campaigns with a strategic plan to win—it is not surprising that union density continues to drop each year.

Is there a way out of this impasse? I argue that the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee (EWOC) provides crucial lessons for how labor can scale up by lowering unionization costs through volunteer organizers, by leaning on digital tools, and by widely spreading the seeds of worker power. Although there are no silver bullets for turning around labor’s decades-long decline, moving in this direction is labor’s best bet to win widely. The fact that many of EWOC’s key strategic innovations have been similarly adopted by other recent bottom-up union campaigns—at Starbucks, in the media, and in auto factories—strongly suggests that the rest of the labor movement should seriously consider adopting a new organizing model.

How EWOC Was Founded

EWOC was an invention of necessity rather than preconceived design. In March 2020, as Covid-19 began sweeping the United States, scores of anxious workers—lacking anywhere else to turn for support—reached out to the Bernie Sanders presidential campaign for help in pressuring employers to provide protective equipment and sick pay. In response, a handful of labor organizers, myself included, from the Bernie campaign, Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), and United Electrical Workers (UE) set up a simple Google form to process the requests. In an ad-hoc manner, we divvied up the workplaces among volunteers with the time to lend guidance to these workers.

To give a sense of what this early pandemic organizing looked like, here is an anecdote from the first group of workers I supported. On March 27, 2020, I connected with a worker I will call Enrique, who worked at the Maid-Rite Specialty Foods meat processing plant in Dunmore, Pennsylvania. “We’re treated like animals, especially the Latinos,” he said in Spanish.

Enrique explained that he and his 200 coworkers had begun organizing themselves via word of mouth and a WhatsApp group. They were afraid to go into work, where the production line obliged them to work virtually shoulder to shoulder, well short of the six feet required for social distancing. A coworker had just tested positive after continuing to come into work, not wanting to lose pay or have a point deducted in the company’s unforgiving assessment system. With help from a labor lawyer I connected him to, Enrique and his coworkers drafted a letter to management insisting that the company start taking serious safety precautions. Enrique and coworkers refused to go into work on March 31. That morning, masked up, he hand-delivered their signed collective letter to management explaining they would not return to work until serious safety measures were taken.

As queries like these kept increasing, our adhoc group started reaching out to an expanding circle of experienced labor leftists willing to volunteer their time to remotely help workers lead workplace fight backs. Most of these volunteers came from DSA and UE, and both organizations granted their official backing early on, as well as sustained volunteers and money, to the nascent effort. Animated by the Bernie campaign’s class-struggle spirit and distributed organizing model, through which digitally connected volunteers run activities normally reserved for staff, EWOC was born.

Committed to teaching the time-tested methods of deep workplace organizing, EWOC’s major innovation has not been in organizing tactics. Rather, its unique contribution has been to build an organizing model that depends on volunteers to do most of the tasks that in unions or nonprofits are generally done by paid full-timers: providing organizing guidance to drives; coordinating other volunteers; responding to workers who reach out, and connecting them with appropriate EWOC organizers; website infrastructure; running communications including social media; holding big organizing trainings; and researching companies and public policy. For precisely this reason, EWOC is scalable, low-cost, and full of lessons for any organization looking to build widespread popular power.

EWOC’s Mission and Impact

Although the initial impetus was to support workers confronting pandemic-related workplace emergencies, EWOC has grown into a larger project aiming to support not only immediate fightbacks, but also worker-initiated unionization. It aims to address the problem identified by Association of Flight Attendants president Sara Nelson: “There are millions of unorganized workers right now who don’t have access to organizing resources, don’t have the support of a traditional union, and don’t know how to take that first step towards building working-class power.” She concludes that “by offering free trainings and organizing guides, and building an army of thousands of volunteers who can offer one-to-one support to any worker in any industry, anywhere in the country, EWOC is playing a crucial role in labor’s revival.”

Similarly wide-ranging support has been given by the best “alt-labor” workers’ centers to some working-class communities in cities across the country. But when it comes to providing organizing guidance, the reach of workers’ centers is limited. Until EWOC was founded, there was no institution in the United States to which any worker—in any industry and in any region—could go to receive organizing support.

Over 5,000 workers have reached out to EWOC since its founding. In 2023 alone, EWOC handed off 65 workplace campaigns representing over 7,000 workers to unions. Over 2,100 workers have participated in our bimonthly, four-part national organizing trainings. And over 1,000 people have become EWOC volunteers, often getting more involved over time via our escalating ladder of engagement, ranging from easy tasks such as texting people about upcoming trainings, to deeply involved tasks such as being an “advanced organizer” guiding new campaigns.

Aiming to help address the organizing vacuum noted by Nelson, EWOC’s process is simple. Any worker in the United States can fill out a short online form and a volunteer organizer will call them back within 72 hours to provide ongoing organizing guidance. In 2020 and the first half of 2021, most of this support went toward direct action campaigns like petitions for personal protective equipment (PPE), paid sick leave, and wage increases. But with the explosion of unionization interest inspired by Starbucks and Amazon in 2022, EWOC’s focus has increasingly turned to helping workers initiate union drives and finding an established union willing to let them affiliate (a task that is sometimes almost as challenging).

EWOC could not function as a largely volunteer-run project without the low-cost coordination, communication, and digital co-presence afforded by new digital tools. A sophisticated digital backend enables EWOC’s volunteers—normally about 250 to 300 are active at a given time—to get onboarded as organizers, to connect with workers who have reached out for support, and to coordinate on the cheap without having to live in the same city or rent out office space. Moreover, digital tools allow EWOC to simultaneously train large numbers of people at once via mass online workshops and extensive organizing materials, rather than having to rely on the labor movement’s traditional approach of expensive in-person trainings for small groups.

Rather than monopolize the significant digital innovations required to manage all these data and coordinate so many campaigns with minimal staff oversight, EWOC has adopted an “open source” spirit, actively sharing its accumulated technological and training know-how with any union or social justice organization looking to adopt a more distributed model. As EWOC’s guiding principles put it, “to build a scalable movement capable of supporting all worker-led organizing efforts . . . we openly share our tools and organizing infrastructure with unions and other allied organizations.”

EWOC’s major limitation is that it is, in the grand scheme, small. Although the project punches above its weight and has expanded every year, relatively few U.S. workers know about it. This reach problem is exacerbated by the fact that it supports the initial steps of organizing, rather than the publicity-garnering final stages coordinated by unions. EWOC’s organizers have taken initiatives to expand its visibility and contacts, for instance by coordinating more with different unions and getting Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and online streamer Hasan Piker to promote the project to their millions of online followers. Even with this help, however, most workers who have reached out to EWOC have been in, or adjacent to, the young radicalized milieus around DSA, Labor Notes, and left unionists across the country.

Expanding this model’s impact to wider layers of working people will require either that larger unions and institutions start lending their support to EWOC or that they adopt its innovations within their own outreach structures. The replicability of this new approach has already been demonstrated by its diffusion to Britain where young labor leftists in summer 2022 teamed up with the Bakers, Food and Allied Workers Union (BFAWU) and the Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen (ASLEF) to found Organise Now!, a project that has consciously imported the entirety of EWOC’s structure and mission—and whose rapid growth has similarly pointed to a vacuum in serious need of being filled.

Lessons from EWOC

Although still limited in reach, EWOC provides a proof of concept for numerous digitally enabled strategic innovations that national unions and allied organizations can incorporate. EWOC’s most important lessons for the broader labor movement are threefold: plant organizing seeds widely; support any worker who wants to organize; and lean as much as possible on volunteers.

Spread Organizing Seeds Widely

Together with similarly bottom-up union campaigns like Starbucks Workers United (SBWU) and the reformed UAW’s organizing across Southern automakers, EWOC has demonstrated the viability of a new strategy of seeding unionization efforts, rather than passively waiting for workers to reach out (“hot-shopping”) or exclusively organizing pre-chosen workplaces (“strategic targeting”). Along these lines, Svoboda describes EWOC’s proactive efforts to provide organizing tools to as many workers as possible as “planting seeds of worker power.” She notes that

not everyone who reaches out to us or who comes to a training will be able to —some get cold feet or others might stop at a petition—but the more people you give those tools to, the more people will actually make it there.

This seeding strategy is a significant innovation, distinct from both traditional small-scale hot shopping and hyper-concentrated union targeting. From the 1990s onwards, most advocates of strategic union organizing have fought labor’s prevailing reliance on hot shopping, arguing (not without reason) against chasing small pockets of discontent because isolated workers lacked the punch to bring industries to the table and because unions’ limited resources should be concentrated on the most strategic targets. Smart organizing was summed up by Stephen Lerner, lead organizer in the Justice for Janitors campaign: “When a union picks a target instead of letting the target pick the union, workers are more likely to win.”[5 ]This remains the prevailing wisdom today among unions with strong organizing traditions. “Our message to the working class is ‘don’t call us, we’ll call you,’” a researcher from one such union half-jokingly told me. As an alternative to hot shopping, these unions have generally focused on targeting relatively large workplaces, especially when these are vulnerable to political pressure.

I am not arguing for a return to hot shopping, in which unions passively wait for workers to reach out and do nothing to transform initial wins into company-wide or industry-wide campaigns. Nor am I suggesting that unions throw out the tactic of targeting strategic workplaces and companies. Unions should put serious funds into efforts like the Inside Organizer School—a project led by SBWU’s founders—to widely train a new generation of salts capable of initiating campaigns at pivotal workplaces and companies.

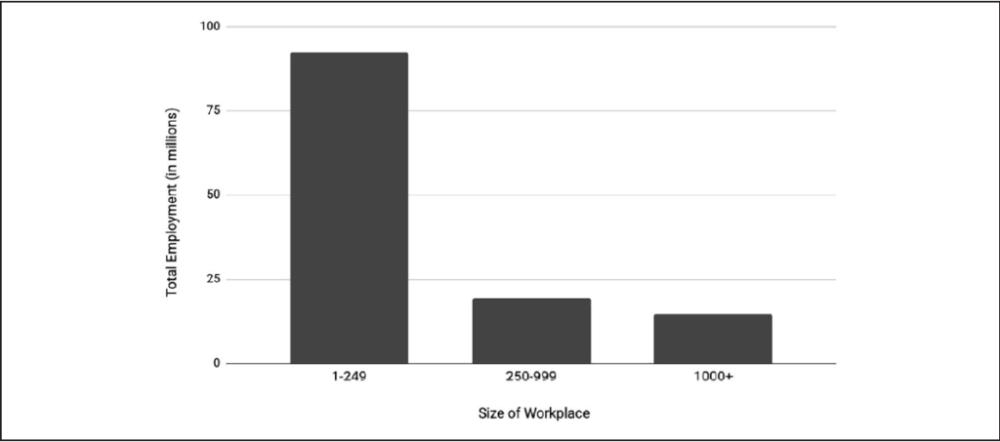

But relying only on this approach is a poor fit for our decentralized economy in which a vast majority of workers work in smallish establishments (see Figure 1). Unlike in the 1930s, our economy and cities no longer revolve around massive, centrally located workplaces like auto and steel factories. Some massive factories and warehouses still exist, but these are now geographically dispersed. And almost all large corporations today depend on thousands of relatively small workplaces that are widely spread out.

Figure 1. Total U.S. employment by workplace size, 2022.

Source: Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In today’s geographically decentralized conditions, union targeting has to be supplemented with proactive efforts to lean on and seed worker-initiated drives across the entire economy, in workplaces of all sizes, in all regions.

Seeding worker-initiated drives in this way is a crucial mechanism to dramatically increase the total number of drives and campaigns in the United States—and to significantly lower their costs, by depending more on worker leaders to drive their initial stages with little to no staff support. The 1 to 100 staff-to-worker ratio of traditional strategic unionization is too expensive to scale up. To organize tens of millions, labor needs to find ways to give large numbers of working people the inspiration and tools to start self-organizing.

As the Starbucks Workers United campaign has demonstrated, seeding can be as proactive and ambitious as targeting, albeit more scattershot. While most of the 400-plus unionized cafes were not specifically targeted by SBWU, most of these also would not have begun organizing without the campaign’s seeding efforts over multiple years.

Along similar lines, rather than only targeting pre-determined factories, the new UAW has actively encouraged all non-union auto workers to start organizing. Rather than targeting specific predetermined factories, the union has cast its organizing seeds widely, focusing on providing material support for those plants where fired-up workers have gone the furthest in collecting union authorization cards on their own. Leaning on the momentum generated by its successful strike of the Big 3 automakers in late 2023, as UAW strategist Chris Brooks explained to me, “we didn’t know—and didn’t want to try to predetermine—where the most heat would be, so we’ve tried our best to fan the flames everywhere.”

From EWOC to Starbucks to Southern automakers, some of the most productive seeding techniques include using high-publicity moments like big union elections and strikes to call on (and provide tools to) other workers to start organizing; holding big online trainings; producing viral social media content to generate new leads; posting digital ads or distributing fliers encouraging people to sign up for organizing support; and developing in-depth, easily accessible training materials for workers to start self-organizing, like EWOC’s Unite and Win: The Workplace Organizer’s Handbook.

Compared to EWOC, unions have far more of an ability to seed at scale. They have over $13.4 billion in unused liquid assets, 14.3 million members who could potentially volunteer, and, through decades of electoral campaigning, they have huge lists of contacts. And as the recent UAW experience shows, they can leverage attention-grabbing actions like strikes to call on (and provide tools to) all workers in a region or industry to start organizing.

Although not all organizing seeds will sprout, a well-funded seeding approach is essential for exponentially raising the quantity of union drives in the United States.

Support Any Worker

EWOC defines its mission as follows: “With the goal of rebuilding a powerful, militant, and democratic labor movement in the U.S., EWOC supports any unorganized worker in any industry who wants to organize their workplace—by building a union and/or fighting collectively for immediate demands.”

Since the biggest challenge facing organized labor is how to massively increase the number of unionization efforts nationwide, why shouldn’t national labor unions or labor federations similarly support any worker looking for organizing help? Such an approach of saying yes—even to small shops, even in towns where a given union does not already have a base, even to fights initially limited to immediate concessions—would significantly expand the number of overall workplace fight backs and union drives, especially as word gets out that labor is committing to new organizing.

Making such a radical shift in approach cannot happen without simultaneously finding ways to lower organizing costs by making organizing less staff-intensive. Saying yes to all workers without breaking the bank via staff hires would oblige the development of extensive online trainings as well as detailed, interactive digital materials to support workers without staff-intensive coaching. It would require establishing gradated approaches for when and how to start dedicating resources to a drive that has caught on, such as providing support at drives’ later stages. It might also require building new, legally firewalled structures to protect the parent union from having to take legal responsibility for every risky action taken by workers they are supporting.

Above all, scaling up to say yes to all workers requires finding ways to inspire and lean on large numbers of volunteer worker organizers. In other words, it would require that labor start structuring itself more like a movement.

Lean as Much as Possible on Volunteers

A shoe-string operation that initially functioned with zero paid staff and that now only has a few full-timers, EWOC has shown that many of the tasks normally done by staff can be effectively done by volunteers. EWOC’s seeding strategy would be impossible without donated labor and developing robust trainings as well as apprenticeship processes to skill-up people from a wide range of experience levels. With EWOC support, for example, many workers who first contact us for organizing assistance eventually go on to become volunteers supporting others. To quote Mike Kemmett from the restaurant Barboncino, which in 2023 became New York City’s first standalone unionized pizzeria: “EWOC didn’t just help us win our [union election] vote. Their support helped to turn bussers and line cooks into labor activists ready and eager to organize other restaurants.”

Depending primarily on volunteers more than staff is pivotal for any project aiming to expand rapidly and widely. “What we straddle is being slightly like an organization, slightly like a movement,” Megan explains. “And blending these has meant that EWOC can scale.” Within an established union, taking this approach would primarily require a far better job of tapping existing members.

None of this is meant to suggest that fulltime organizers and union resources are unimportant. Capacity and accumulated experience are crucial, and staff are an essential vehicle to transmit both. The problem is that most unions use this correct general argument to justify their specific (staff heavy) division of labor, without seriously probing the potential to scale up by deploying experienced full-timers and union resources in a new way.

In my forthcoming book on worker-to-worker organizing, We Are the Union (University of California Press, 2025), I detail how Starbucks Workers United, the NewsGuild, and UE’s higher-ed initiatives have recently shown that rank-and-filers—especially those who have recently unionized their own workplaces and who have themselves received serious organizing training—are capable of providing good organizing advice to others. The NewsGuild, for example, has successfully unionized over 10,000 workers since 2017 and won dozens of first contracts through its Member Organizing Program, a worker-to-worker project premised on the idea that workers can and should learn every organizing task normally reserved for staffers.

It is crucial to underscore that getting large numbers of people to volunteer is not only an organizational and technical question. Above all, it is a question of ambition and political vision. The experience of EWOC suggests that most potential volunteers will sacrifice their time for projects that they feel passionately about, that they have ownership over, and that are taking on the systemic injustices of capitalism. It is no accident that EWOC’s volunteers are mostly leftists—and that its institutional backing is from this country’s emblematic left led union (the UE) and its largest socialist organization Democratic Socialists of America (DSA). As was the case in the 1930s, a big labor breakthrough requires ambitious strikes and organizing drives capable of tapping young radicalized organizers as well as broader layers of working people.

Whether in the Guild or EWOC, it is important to acknowledge that wagering on worker leadership does come with downsides. Such an approach will, for example, generally translate into a less tightly run ship for union campaigns. But this is a necessary price to pay for involving far more people and organizing more widely. Stephanie Basile from the NewsGuild captures this dynamic:

“The big drawback is that you don’t know what’s going on everywhere and maybe a member is not doing it as perfectly as an experienced staffer. But building a movement is always going to be messy and the strengths far outweigh [the drawbacks]. If we really want as many people as possible out there leading and building power, I shouldn’t know what every member organizer is doing—and we need to have confidence in them.”

Together with like-minded union campaigns, EWOC has demonstrated in practice that a new approach to unionization is possible. If labor as a whole adopted its distributed organizing innovations and lofty, class-struggle ambitions, this would go a long way toward enabling unions to scale up.

But moving in this direction will not be easy for a labor movement deeply weighed down by routine and risk aversion. Even though conditions for new organizing have been exceptionally favorable since 2020, few unions have gone all in to seize the moment. Now is the time.

Notes

1. Thomas A. Kochan, D. Yang, W. T. Kimball, and E. L. Kelly, “Worker Voice in America: Is There a Gap Between What Workers Expect and What They Experience?” ILR Review 72, no. 1 (2019): 3-38.

2. On the high cost of workplace organizing and more scalable alternatives, see Eric Blanc, We Are the Union: How Worker-to-Worker Organizing is Revitalizing Labor and Winning Big (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2025). All quotes in this article, unless otherwise noted, come from interviews done with the author in 2022, 2023, and early 2024 as part of research for this book.

3. Linda Markowitz, Worker Activism after Successful Union Organizing (Abingdon: Routledge, 2000), 93. 3. Linda Markowitz, Worker Activism after Successful Union Organizing (Abingdon: Routledge, 2000), 93.

4. Daniel Galvin, Alt-Labor and the New Politics of Workers’ Rights (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2024) shows how workers’ centers have effectively expanded their reach by focusing more in recent years on passing and enforcing local and statewide laws.

5. Stephen Lerner, “An Immodest Proposal: Remodeling the House of Labor,” New Labor Forum 12, no. 2 (2003), 20.

6. Eric Blanc, “Worker-to-Worker Organizing Goes Viral,” New Labor Forum 33, no. 1 (2024): 77-83.

7. On labor’s funding reserves, see Chris Bohner, Labor’s Fortress of Finance: A Financial Analysis of Organized Labor and Sketches for an Alternative Future: 2010-2021 (Radish Research, 2022), 1.

Author Biography

Eric Blanc is an assistant professor of labor studies at Rutgers University, the author of We Are the Union: How Worker-to-Worker Organizing Is Revitalizing Labor and Winning Big (University of California Press, 2025), and an organizer trainer in the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee.

Spread the word