Here in the USA we like to consider ourselves, as Ronald Reagan said in his 1989 Farewell Address to the Nation, “the shining city upon a hill. . . . God-blessed, and teeming with people of all kinds living in harmony and peace; a city with free ports that hummed with commerce and creativity.”

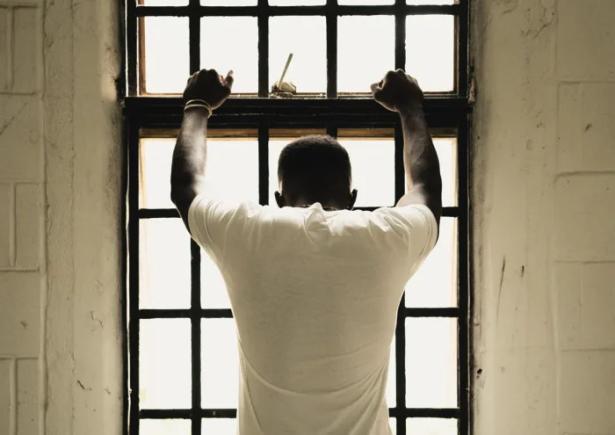

But in some ways, we are not a beacon of freedom and democracy, and one of them relates to our criminal justice system. One Internet site noted what others have also indicated: that the differences “between the European and American penal systems were astounding. Germany and the Netherlands [for example] incarcerate one-tenth the rate of the U.S., where sentencing time is considerably longer.” There is also the racial element in our system. To cite just one statistic, in 2021 Blacks were imprisoned at a rate about five times that of Whites.

Just last month a book appeared co-authored by one of our best-selling authors, John Grisham, and it highlighted another defect in our prison system. Its title? Framed: Astonishing True Stories of Wrongful Convictions. Grisham’s co-author is Jim McCloskey, who in 1983 founded Centurion Ministries, which by late 2019 had secured the release of 63 wrongly convicted persons in the the USA and Canada. In Framed, each author wrote about five “framed” cases, and in his portion of the book’s preface McCloskey wrote, “The twenty-three defendants caught in the web of these ten wrongful convictions needlessly spent decades in prison until the truth of their innocence finally emerged and set them free. Four landed on death row, two of whom came within days of execution, while one was tragically executed.”

He then added, “These convictions were not caused by unintentional mistakes by local law enforcement or misidentification by well-meaning eyewitnesses or honest but erroneous forensic analysis. No, they were rooted in law enforcement misconduct and chicanery, men and women hell-bent on clearing cases or gaining a conviction through a wide variety of illicit means—subornation of perjury, secret deals with criminals in exchange for their fabricated testimony, coercing witnesses into false testimony or suspects to falsely confess, use of discredited or inept forensic analysts, suppression of exculpatory evidence from the defense, or other acts that obstructed justice and resulted in the ruination of innocent lives to the relief of the actual perpetrators.”

Another recent (Sept. 2024) book that highlighted wrongful convictions is Dan Slepian’s The Sing Sing Files: One Journalist, Six Innocent Men, and a Twenty-Year Fight for Justice. Slepian is a producer of reports and podcasts for "Dateline NBC," and he has been examining such convictions for a few decades.

In a recent interview he explained how he got interested in the subject: “I grew up believing that the justice system worked just the way it should. . . . [but in later years] I was able to see a justice system that I never knew existed, a very dark and ugly underbelly that is really how the system often works.” He recognizes that his initiation to this “underbelly” was a New York case that involved the murder on Thanksgiving night 1990 at the Palladium nightclub. As he later heard about it from a detective, two Hispanics, David Lemus and Olmedo Hidalgo, were charged with the crime and spent 15 years in prison before one of Slepian’s programs aired in 2005. It helped lead to a judge overturning the conviction in 2005.

Slepian recognizes that “racism and corruption are part” of the wrongful-conviction problem, but also has observed that there are additional causes. In the twenty-first century, his book tells us, he has

witnessed the American criminal justice system from every perspective. I’ve been embedded with detectives, prosecutors, and defense attorneys and followed them and their cases for months, sometimes years. I’ve interviewed countless murderers, judges, and jurors. I’ve gotten to know many victims of crime and have come to understand the devastating impact it has on them and their families. I’ve spent several hundred days inside prisons across the United States with the wardens who run them, with convicted killers sentenced to death, and with the corrections officers who walk those dangerous tiers every day, hoping to go home unharmed. And I’ve toured prisons in other countries. I even slept in a cell for two nights in Louisiana’s Angola prison. . . . Proximity has taught me one overwhelming truth: we have an undeniable crisis on our hands. There are roughly two million Americans locked up, more than in any other country, and our recidivism rates lead the world. . . . I’ve come to see the inhumanity and irrationality of that system, and how its worst aspects are revealed by the way it handles wrongful convictions.

Furthermore, he discovered “what false imprisonment means not only for the individuals who are wrongly removed from society but also for their parents, partners, and children. As tragic as these injustices are for innocent people in prison, they have a cascading generational impact on those around them and on society that is hard to measure.”

Regarding how many wrongful convictions there have been, Slepian writes that “the number is staggering.” He suggests the total number could be between 100,000 and 200,000, but only around “thirty-five hundred people have been exonerated in the past thirty years.” Why so few? Slepian explains that “the system . . . isn’t built to get people out. It’s built to keep them in—even when . . . there is clear evidence that they don’t belong there. . . . even when some prosecutors are presented with irrefutable proof of innocence, the default is resistance as opposed to curiosity or concern.”

Besides Grisham, McCloskey, Centurion Ministries, and Slepian there are others who have worked to free the wrongfully convicted. Slepian mentions the Innocence Project, whose website states, “We've helped free more than 250 innocent people from prison.”There’s also the Equal Justice Initiative, which “challenges wrongful convictions and exposes the unjust incarceration of innocent people that undermines the reliability of our system.” And there’s the The Exoneration Project, whose website proclaims, “We fight to free the wrongfully convicted, exonerate the innocent, and bring justice to the justice system.” (For a partial, but exhaustive and well researched, list of wrongful convictions in the USA since 1805, readers can view Wikipedia’s “List of Wrongful Convictions in the United States.” And for a recent execution of a Black man, in September 2024, that may have been innocent, see here.)

Finally, regarding wrongful convictions, what does the future look like? Unlike futurists, we historians have some certainty about the past, but for the future we have only guess work. Yet with the incoming Trump second term, matters don’t look good.

In his The Sing Sing Files, Slepian mentions our past—and now future—president. Here are his exact words, “One of the biggest stories back then had happened in 1989—the rape of a jogger in Central Park. Five teenagers were arrested and paraded in front of dozens of rolling cameras. The “Central Park Five”—or the “Exonerated Five,” as they became known after their convictions were vacated in 2002 [my bolding]—were described as a group of “wilding teens” who brutally raped a woman and left her for dead. Donald Trump ran an ad in Newsday calling for their execution, headlined: “Bring Back the Death Penalty! Bring Back Our Police!”

What is especially troubling is not only the call for “the death penalty”—with Belarus (Russia’s ally) being “the only country in the continent of Europe that still carries out the death penalty”—but that the five convicted teens were innocent. And Trump’s rush to judgment 35 years ago has gotten even intense at the present.

Putting aside the glee over his election manifested by the private prison industry—yes some prisons are run for profit—due to Trump’s plans for dealing with illegal immigrants, we can instead look at some of his statements for dealing with his political enemies.

Regarding former congresswoman Republican Liz Cheney, he posted in May 2024: "She should go to Jail along with the rest of the Unselect [referring to the House Jan. 6 select committee] committee." In September, he threatened “long term prison sentences” for election officials and politicians who “could cheat in the 2024 election.” In the same month about Supreme Court critics he declared, "These people should be put in jail the way they talk about our judges and our justices, trying to get them to sway their vote, sway their decision." (In November 2024, the Axios website posted more “enemies within” that Trump hoped to jail, and the selection of Rep. Matt Gaetz as his nominee for attorney general just reinforced the alarm that a President Trump might imprison innocent people, guilty only of non-violently opposing him.)

In summary, our problem with “innocents in U. S. prisons” shows more signs of increasing rather than diminishing.

Walter G. Moss is a professor emeritus of history at Eastern Michigan University. He is the author of Russia in the Age of Alexander II, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky (2002). For a list of all his recent books and online publications, including many on Russian history and culture, go here.

Spread the word