“Has anyone else’s child received this text message? I’m thinking it’s a prank, but there’s nothing funny about it! I’m livid!!”

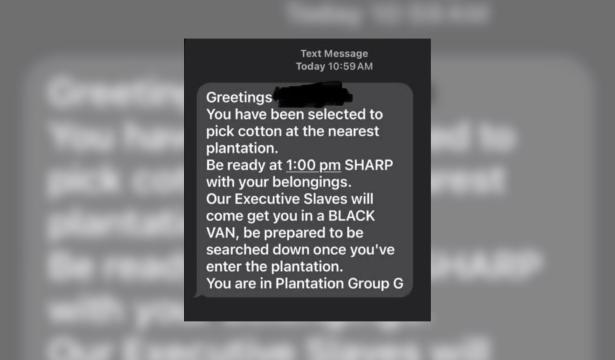

That was the message one Paloma Creek, Texas, resident left on a local Facebook group on November 6, 2024, hours after Donald Trump was elected President of the United States. The resident also shared an image of a text they said was sent to their child from an unknown number, asking them to report to “pick cotton at the nearest plantation.”

One staff member in the Denton Independent School District (ISD), which serves more than a dozen Dallas-Fort Worth area municipalities including Paloma Creek, tells The Progressive they heard from colleagues that students reported receiving similar messages. While the staff initially assumed the texts were sent by other local children as a bullying tactic, news outlets across the US soon began reporting on a number of similar incidents.

Nearly identical versions of the racist mass text have reportedly been sent to Black Americans in at least thirty states, including to children as young as thirteen. In addition to Dallas-Fort Worth, the messages have been received in regions with significant Black populations, including Detroit, Washington, D.C., and Gary, Indiana. CNN reported students of at least three historically Black colleges and universities received versions of the message.

Middle school theater instructor Carrie Stephens, who teaches in the Denton ISD, says she learned about the texts from a post on a neighborhood social media page. After seeing a post about similar messages from someone in a different state, she realized the scale of the incident went far beyond Denton County.

“I was in disbelief that anyone would have the audacity to do anything like this,” Stephens says. “But immediately, my thought went to, ‘Well, we did just elect someone who encourages that, or at least doesn’t discourage it.’ And it’s making a lot of people bold.

Had the incident occurred when she moved to her current neighborhood in 2018, Stephens says, she would have considered the spam messages “very out of character” for the community. “But in the last few years,” she says, “I’ve noticed a lot more people saying a lot more outlandish things.”

Denton County, which is home to the University of North Texas, is a “purple” area at the northwest edge of the Dallas-Fort Worth metropolitan area’s Democratic bubble. The region has been a hub for a vibrant Black community since the end of the Civil War, when formerly enslaved people established freedmen’s towns. Today, Texas has the largest Black population in the country, with much of the community concentrated around Dallas-Fort Worth and Houston.

But the region is also known for its long history as a center for organized white supremacy. In the early 1920s, Dallas was home to what was supposedly the largest Ku Klux Klan chapter in the world, with a 13,000-strong membership that, according to Dallas Magazine, “presumably represented about one out of three eligible men in Dallas.” During this time, KKK members held roles across all levels of law enforcement, including district attorneys, sheriffs, police commissioners, and judges.

While it’s now clear that the campaign was nation-wide, some in Denton County have described feeling unnerved by such an open display of racism close to home. Stephens doesn’t only teach in the Dallas-Fort Worth suburbs—she also has two children enrolled in the Denton ISD. “My girls go to the high school,” Stephens says, “and they came home the next day, and they were telling me about kids who had gotten the messages. They asked why anyone would do that, and I told them that some people don’t understand how this affects the people receiving the message, and some people know exactly what it will do.”

Amber Sims, the CEO of a Dallas-Fort Worth racial equity organization called Young Leaders, Strong City—one of just two major organizations of its kind in the area—urges parents to check in with their children and discuss the racist messages, to affirm “their right to be here like everyone else . . . the reality of the increased racism and bullying we are seeing directed at certain groups simply for existing.”

“Parents can also model this behavior isn’t okay by countering the racist messages,” Sims says, “and ensuring their children know there is no place for bigoted words or actions. There is room to disrupt this behavior at all levels.”

William C. Anderson, an activist who has written extensively on Black history and liberation, says that people like the ones who sent the text messages “are going to be emboldened and feel more protected by the current administrators of the state. And they’re certainly not wrong to feel that way. White supremacy and Christian nationalism are being made explicit in ways this country often tried to downplay.”

Despite statements from area residents who received texts, as well as national news reports confirming others had received the spam messages in North Texas, a spokesperson for Denton County Sheriff’s Department said there had been no reports of the messages to their office. Another official with the Denton Police Department said “no police reports have been filed” with the department regarding the spam texts, though they encouraged affected residents to do so. In fact, none of the other local police departments that are served by Denton ISD and could be reached for comment had received reports related to the incident, though at least one media report indicates the Dallas FBI office is involved in the investigation.

A spokesperson for the school district also declined to confirm whether any Denton ISD students had reported receiving text messages, particularly in the hours before it was clear the incident was more than simple bullying. The spokesperson questioned whether the Paloma Creek Facebook post was real, and if the child who reportedly received that message actually attended Denton ISD, though the same official said they knew someone in the area who had received a message. It’s relevant to note the post was almost the same as those reported across the country and at least two staff said they had seen it before major news reports of the incident. The district official did mention that services were available to any students who may have been affected.

On November 7, the Federal Bureau of Investigations said in a statement that it was working with federal authorities, including the Justice Department, to investigate the incident and any potential for violent acts associated with the texts. A week later, the agency also confirmed Latinx and LGBTQ+ community members had received similar messages, with some recipients reporting “being told they were selected for deportation or to report to a re-education camp”, and that some people had received hateful messages via or email. Some texts also reportedly mention the incoming Trump Administration, though a spokesperson for the Trump campaign told media the campaign “has absolutely nothing to do with these text messages.”

The messaging app TextNow appears to have been used to send some of the messages, which the Nevada Attorney General’s Office said in a social media statement it believed were likely “robotext messages.” Cori Faklaris, an assistant professor of software and information services at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, told the Associated Press that whoever organized the spam campaign likely bought the recipients’ data online and used machine-learning algorithms to predict individuals’ race or ethnicity. That hypothesis would explain why one teacher in Gary, Indiana—which, according to 2023 U.S. Census data, is 77.6 percent Black—tells The Progressive that dozens of students at their school reported receiving the texts about being enslaved, including many white children. One of those students even mentioned their cell phone was registered in the name of a Black relative.

But the national barrage of hateful spam texts has not been the only incident of racist intimidation in the two weeks since the presidential election. And it extends beyond the South, proving racism and xenophobia are not bound by geography. In Howell, Michigan, a group of five fascists recently waved Nazi flags outside of an American Legion, where a local theater troupe was putting on The Diary of Anne Frank, a stage adaptation of the journal of a young Jewish girl who died in the Holocaust. Local media reports said police “had no grounds” to ask the demonstrators for identification as their protest was “peaceful.” Another similar rally was reported in nearby Fowlerville.

One week later, just 200-odd miles south in the more liberal city of Columbus, Ohio, a group of nearly a dozen masked neo-Nazis marched through the Short North neighborhood carrying swastika flags. Zach Klein, Columbus’s city attorney, released a statement on social media telling the demonstrators to “take your flags and the masks you hide behind and go home and never come back.” He also said his office would collaborate with law enforcement to monitor what he called a “hate group.” (Police told reporters that some of the demonstrators had been detained, but none were arrested.)

Just fifty miles east of Columbus, a disinformation campaign against Haitian migrants in Springfield, Ohio resulted in threats of violence and local media reports of growing neo-Nazi activity, with one Southern Poverty Law Center analyst calling the state a “hotbed for hate groups.” And in northern Indiana this week, the Trinity White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan reportedly said it left fliers on vehicles and at homes in several towns near Gary, including Michigan City, Valparaiso, and South Bend, warning undocumented immigrants to leave the United States before Trump’s Inauguration.

Like the once strictly segregated Dallas-Fort Worth area, many of the established communities of color targeted by white supremacists in recent weeks have a complex history of systemic racism. In Democratic-leaning Gary, Indiana, less than an hour south of Chicago, once middle-class neighborhoods are now in substantial decline after the federal and state governments abandoned the steel mills, offshoring once well-paid union jobs and pivoting towards automation.

In spite of the history of racism, and the racist threats that have emerged in recent weeks, Sims sees the mass text incident as a chance to push for change. “I think this is an opportunity for our communities to continue to organize,” she says. “Teach our history, attend organizing trainings, follow your school board and city council, and be in community to create processing spaces, spaces for encouragement, planning and joy.”

As an educator, Stephens is hopeful those who organized the racist messaging campaign targeting Black, Latinx and LGBTQ+ Americans will be caught and brought to justice. But Anderson believes the answer to overcoming the threat of racist violence lies with new generations. “Young people need to learn their history and work together to build popular education programs that aren’t solely reliant on the state,” he wrote in an email to The Progressive, “so they can build and spread awareness around resisting the increasingly hostile racism of this society.”

Nyki Duda is a writer and editor focused on social movements and the rise of the far right. Her work has appeared in Dissent, NACLA, and In These Times.

Since 1909, The Progressive has aimed to amplify voices of dissent and those under-represented in the mainstream, with a goal of championing grassroots progressive politics. Our bedrock values are nonviolence and freedom of speech. Based in Madison, Wisconsin, we publish on national politics, culture, and events including U.S. foreign policy; we also focus on issues of particular importance to the heartland. Two flagship projects of The Progressive include Public School Shakedown, which covers efforts to resist the privatization of public education, and The Progressive Media Project, aiming to diversify our nation’s op-ed pages. We are a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

Spread the word