They just look at you like you’re nothing,” said a housekeeper from the Hyatt Regency hotel in downtown Buffalo, New York.

Sitting with me for a conversation in her East Side apartment, the housekeeper, who requested not to be named due to fear of retaliation, spoke of slashed hours and stagnant pay, arduous and unfair workloads, and racist treatment and verbal abuse from managers so severe that it has sent her running to the bathroom in tears.

But when she spoke about the belittling gaze of her employers — the feeling that immigrant workers like herself are seen as “nothing” by the hotel’s management – her words seemed to capture the deep nature of her grievances.

“They’re mistreating the workers, especially the immigrants,” she told me. “They should respect the workers that are making the hotel look clean.”

These sentiments also explain why she and other Hyatt workers are taking great risk by supporting a union drive at their hotel.

“All that I’m looking for is for the union to support us,” she said, “so us working at the hotel will be respected, and they can look at us like humans.”

Over the past several months, a battle has been unfolding at the Hyatt Regency in Buffalo that pits two sides of the city against each other: its love affair with developers, who city leaders have turned to as post-industrial saviors, and its identity as a union town, filling up with non-union jobs in low-wage sectors like leisure and hospitality.

On one side of this battle is Douglas Jemal, a real estate mogul who swooped into Buffalo from Washington, D.C. a decade ago to gobble up dozens of storied commercial and residential properties across the city, including Buffalo’s only skyscraper. A darling of local media and civic elites, and a big donor to city and state officials, Jemal has been awarded millions in public subsidies. He is a close friend of the Kushners, and he had a wire fraud felony conviction pardoned by Donald Trump in 2021. Jemal’s imprint across Buffalo is inescapable.

On the other side are the workers at the Hyatt Regency in downtown Buffalo, a full-service convention hotel surrounded by sports stadiums and trendy restaurants. Jemal acquired the Hyatt in 2021. Last August, these workers announced a union drive to improve their working conditions and win more voice and dignity on the job, but they say they were met with a ferocious union-busting campaign that included numerous firings of pro-union workers.

Behind its “revival” narrative, Buffalo remains one of the nation’s poorest cities. It’s a labor stronghold, but its hotels are almost entirely non-union, even as their workers help undergird the city’s so-called revitalization. While developers like Jemal enjoy big subsidies and tax payment schemes that benefit their own properties, Buffalo’s city budget faces a massive $60 million deficit.

In many ways, the battle at the Hyatt is a proxy over whose interests will prevail in the new Buffalo: wealthy developers who receive lush subsidies, or workers fighting for good union jobs in industries like leisure and hospitality that prop up the city’s purported renaissance.

“They Look at Us Like We Don’t Have Value”

Rumblings of a union stirred among some Hyatt workers in 2023, but the idea gained momentum during the busy summer of 2024, especially among a core of front desk workers. One of them was Luke Sills, who has worked at the hotel for nearly two years. In 2023, the Hyatt Regency Buffalo named Sills its “Employee of the Year.”

Sills is one of the rank-and-file leaders of the union drive at the Hyatt. “Every worker in the building knows how we should be doing things differently,” he told Truthout. “Having a voice to make this hotel a place that we can be proud of was a big motivator for us deciding to unionize.”

Luke Sills holds his 2023 Hyatt Buffalo Employee of the Year award. (Luke Sills)

Truthout spoke with current and former Hyatt workers — front desk agents, restaurant servers, housekeepers, baristas — who described a range of grievances and a workplace marked by dysfunction and disrespect toward employees.

Workers expressed concerns around wages, understaffing, inconsistent scheduling and reduced hours. But their issues went much further.

They spoke of a rundown hotel that is not adequately maintained, leaving guests to lash out at employees. Broken ovens and espresso machines go unfixed. The carpets are old and grimy, they say. The heating and air conditioning systems run poorly.

“The rooms are just falling apart,” said Sills. “These problems with the hotel ruin the guest experience.”

Workers say the hotel is chaotic and mismanaged. Employees do work beyond their job descriptions for no extra pay to compensate for inept managers. Understaffing leaves hotel departments scrambling to get through the day.

Tiba Salvatore told Truthout that for weeks after she started working at the front desk last July, she didn’t even have a manager. “Right away, I noticed the dysfunction at the Hyatt,” she said.

For many, the worst part is the disrespect and humiliation workers face, with some recounting racist slurs by managers and verbal abuse toward immigrant housekeepers who make up the hotel’s largest department.

The housekeeper I spoke with in her East Side apartment described heavier workloads for non-English speakers and reductions in her hours without explanation. She says she has not seen a wage increase in years.

She also said she’s often ordered to do tasks beyond her role at the Hyatt, and described one incident where she was yelled at by her supervisor after she refused.

“He was loud and aggressive toward me in front of people,” she said. “The managers are racist, and I don’t have any right to express myself. All this happens to us because we’re immigrants and our English is not enough.”

Left in tears after the incident, she says she can’t leave the job. Like other housekeepers, she depends on the income.

“That’s why, after all the humiliation, I still go.”

“Workers Need to Be Respected”

Multiple workers told Truthout that this kind of treatment was a key motivation for unionizing.

“There’s this culture of disrespect and abuse where management treats immigrants like they’re stupid,” said Sills. “I became friends with some of these people and realized how cruel it is.”

Sills was among the half-dozen workers who formed a union organizing committee affiliated with Workers United, the same union that organized the ground-breaking Starbucks union drive that originated in Buffalo.

On July 31, 2024, the organizing committee announced the union in a letter to Jemal; the hotel’s general manager, Steve Jarmuz; and Craig Smith, the CEO of Aimbridge Hospitality, who operates the hotel. The letter asked Jemal and the Hyatt management to agree to Fair Election Principles safeguarding workers’ rights to unionize without company interference.

“I was hoping they might listen to me as someone who clearly cares about the hotel, but who wants to have a voice to make this place better and believes that workers need to be respected,” said Sills.

The workers never received a response.

The union drive kicked into high gear. Organizing committee members knocked on doors and spoke with coworkers. Workers started wearing union buttons on the job. Signed union cards began to pile up. The union quickly gained strongholds at the front desk and lobby area and in the restaurants and the hotel’s Starbucks.

A Hyatt Workers United button that workers have worn during their union drive. (Luke Sills)

Edgar O’Connell, a restaurant server, was one worker who joined up. He was upset with things like understaffing and disrespectful treatment from management. He told Truthout he hoped the union “could make a difference in the way that the hotel was run” and wanted “respect for us workers as the people who are making the hotel run.”

The union estimates they had around 70 percent support among customer-facing “front of house” workers across the hotel when they filed for a National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) election in early September 2024. They hoped that winning a union for “front of house” workers would provide the foundation for organizing the hotel wall-to-wall, especially the several dozen housekeepers.

However, right after workers announced the union, they say, the union busting began.

“It Felt Like a Witch Hunt”

Multiple workers say the Hyatt management launched a multi-pronged offensive to smash the union drive, firing pro-union workers and creating a climate of fear around the union.

Two days after the organizing committee sent its letter, Sills was pulled into a meeting with the hotel’s top management and grilled with questions about the union.

“They were trying to talk me out of it,” said Sills. “The tone was very much intimidation and veiled threats.”

Other workers told Truthout of similar meetings. They say out-of-state consultants held captive audience meetings with workers where they stoked fear and misinformation about the union. Workers say management was monitoring them with security cameras and scouring their social media accounts.

Pro-union workers started getting fired or pushed out. The hotel’s Starbucks, one of the strongest pro-union departments, was a main target.

Garion Lopez, a barista who was part of the organizing committee, told Truthout that Starbucks workers were interrogated and accused of theft. The common practice of occasionally giving friends free drinks was suddenly being treated as a fireable offense. Several baristas were suspended and fired, while others left under the pressure.

“It felt like a witch hunt,” said Lopez.

Sills said that “every single person they fired had signed a union card.”

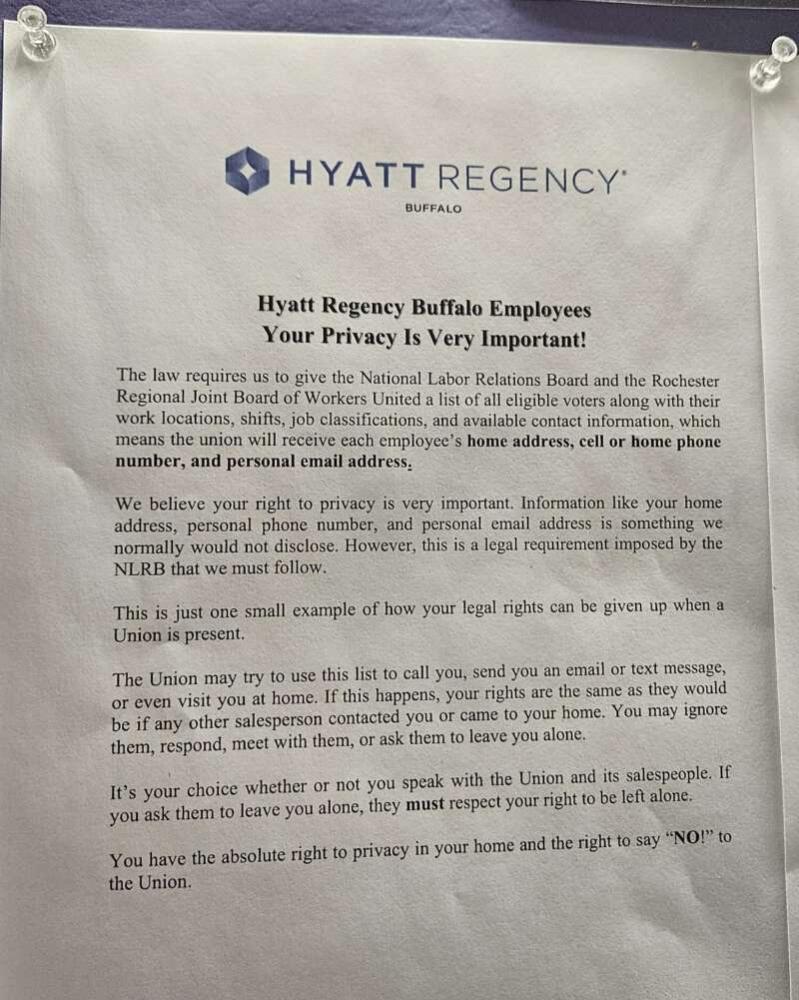

One Hyatt worker shared a company flyer with Truthout that was posted in the breakroom implying that the union was a threat to workers’ legal rights and privacy.

An anti-union flyer that Hyatt management posted in the employee breakroom/cafeteria. (Edgar O’Connell)

According to labor expert John Logan, this is “a really standard anti-union flyer” whose variations have been used in anti-union campaigns for decades.

“The intention is to give the impression that unions are invading the privacy of workers, even though the reason that unions conduct home visits is that employers deny them access to the workplace and make it as difficult as possible for them to communicate with workers,” Logan told Truthout.

“Generally speaking,” Logan added, “employers are the ones who bombard workers with anti-union texts and emails with messages like this one and force them to attend anti-union meetings.”

Workers say the most chilling effect of the Hyatt’s anti-union campaign was on housekeepers. Many are immigrants who face language barriers and whose families depend on their jobs at the Hyatt. They cannot easily find new work.

“They were telling them the union would cut wages” and that it’s “there because it wants your money,” said one housekeeper. “They traumatized us.”

Housekeepers saw pro-union workers being fired and pushed out. “All those people were very scared to lose their jobs,” said Salvatore.

On October 9, the union held a press conference in front of the Hyatt where Sills referred to management’s anti-union offensive as a “terror campaign.”

“It’s been really shocking and a bit horrifying to see the ways that they responded to our campaign so far,” he told reporters.

Hyatt workers announcing their union drive at a press conference outside the Hyatt Regency Buffalo on October 9, 2024. (Derek Seidman)

The Hyatt’s anti-union blitz took a heavy toll on the union drive. Workers estimate that, after several weeks, front-of-house support for the union fell from 70 percent to around 50 percent.

Sills says the hotel’s brazen firings “showed everybody that they were willing to break the law to bust the union.” Under these circumstances, Workers United made the tough call to temporarily pull the NLRB election in early November.

Meanwhile, the union filed nearly three dozen Unfair Labor Practice (ULP) charges with the NLRB during October alleging a slew of illegal acts of intimidation and retaliation against workers. These charges range from “unlawfully interrogating an employee by asking them if they signed a union authorization card” to “telling employees that their pay and benefits were ‘frozen’ because of the union campaign.”

One ULP charge stated that the employer engaged in “threatening employees that the hotel may have to close if the employees unionize,” an allegation that multiple workers mentioned to Truthout.

Truthout reached out to Jemal to ask about this allegation around closing the hotel but received no response. Truthout also reached out to Jemal, Hyatt Regency Buffalo General Manager Steve Jarmuz, and Aimbridge Hospitality for comment on worker grievances and anti-union allegations discussed in this article, but received no responses.

The union also requested a remedial bargaining order that would compel the Hyatt to recognize and bargain with the union, alleging that a fair and free election is no longer possible because of the company’s anti-union behavior.

“A Union Town, Except for Hotels”

Not the industrial powerhouse it once was, Buffalo remains a labor stronghold. Union halls dot the city landscape. Any local political candidate covets the labor vote. Nearly a quarter of workers in the area have union jobs.

But not Buffalo’s hotel workers.

“Buffalo is a union town, except for hotels,” Gary Bonadonna Jr., the regional head of Workers United, told Truthout.

At workplaces like the Hyatt, Buffalo’s identity as a union town is clashing head-on with its commitment to developers like Douglas Jemal, who receives millions in public subsidies while, workers say, his managers at the hotel feverishly fight a union drive.

Bonadonna Jr. sent a letter to Jemal, shared with Truthout, demanding a fair union election at the Hyatt and the reinstatement of fired workers. He never received a response.

“We support developers who take an interest in Buffalo and want to invest in the city,” said Bonadonna Jr. “But it can’t be at the expense of the workers.”

The union is hoping that pressure from the labor movement and the wider Buffalo community will convince the Hyatt, which hosts many large gatherings, to respect their workers’ right to unionize.

Recently, the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW), which has held events at the hotel, sent the Buffalo Hyatt a letter, viewed by Truthout, supporting the workers’ right to unionize. Ed Braukus, international representative for IBEW 3rd District, told Truthout that the Hyatt is “pretty much off the list” for future IBEW meetings in Buffalo right now. “We’re not going to patronize a place that’s actively violating workers’ rights to organize,” he said.

“We’re not calling for a boycott now,” Bonadonna Jr. told Truthout, “but I think eventually customers can decide to support this business or not after learning what happened to the workers who tried to organize.”

“The Kind of Economic Development We Need”

Jemal and Douglas Development are not done with hotels in Buffalo. He was recently awarded $12.5 million in state subsidies to redevelop the historic downtown Statler building, which will include 200 hotel rooms.

Jemal has also negotiated a scheme that directs his tax payments toward his own properties rather than the city’s general fund. All this comes as Buffalo faces a huge $60 million budget deficit.

“Jemal is using the developer toolkit of making agreements that keep his money out of the general fund and focus his tax contributions around his own developments,” Andrea Ó Súilleabháin, executive director of the Partnership for the Public Good, a community-based think tank in the Buffalo-Niagara region, told Truthout.

“That’s problematic in a city like Buffalo, where we have a revenue crisis, which means many of our neighborhoods get neglected,” she added.

Ó Súilleabháin wants to see stronger criteria around union rights from state and county agencies that issue subsidies to developers. “If you’re taking public money, you have to be recognizing unions across all of your projects,” she said.

She adds that tackling Buffalo’s chronic poverty depends on creating good union jobs at workplaces like hotels. “The only way to counter Buffalo’s long-term high poverty rate is to improve jobs in sectors like leisure and hospitality and drive their wages and benefits up,” she said.

“And of course,” she adds, “the right to unionize is central to that.”

Truthout reached out to local elected officials for comment about the allegations surrounding the Hyatt and asking if they felt subsidies to Jemal should be contingent on workers’ rights to organize being respected across his properties.

None of Buffalo’s Common Council members responded, nor did Erie County Executive Mark Poloncarz. Over the past several years, Buffalo’s city government and the Erie County Industrial Development Agency — where the Mayor of Buffalo, President of the Buffalo Common Council and Erie County Executive all have seats on the board of directors — have supported PILOT deals and subsidies for Jemal.

According to campaign finance records, Poloncarz has reported receiving $28,000 from Jemal since 2019, while Common Council Majority Leader Leah Halton-Pope received $2,500 in 2023 and Council Member Joel Feroleto received $1,000 since 2022.

Truthout additionally reached out to Buffalo Mayor Christopher Scanlon for comment but received no response. Scanlon is also a candidate in Buffalo’s mayoral Democratic primary race this year, and Truthout reached out to three other candidates, State Senator Sean Ryan, Common Council member Rasheed Wyatt and former Buffalo Fire Commissioner Garnell Whitfield, for comment.

Only Ryan responded, calling the allegations against the Hyatt “serious and concerning,” and said he’s “long supported attaching basic labor standards as a condition of receiving public subsidies, a commonsense safeguard against anti-union tactics like those being alleged.”

“The ability to organize is a fundamental right and taxpayer dollars should not be used to support anyone attempting to deprive their workers of that right,” Ryan added.

Jemal, a big donor to former Buffalo Mayor Byron Brown, has not contributed to mayoral candidates so far this election, according to the most recent campaign disclosures. Other major Buffalo developers have donated heavily to Scanlon, who also held a December 2024 fundraiser at Jemal’s Seneca One building. In May 2023, Ryan’s State Senate campaign reported a $950 in-kind contribution from Jemal’s Richardson, a rental fee waiver for a fundraiser.

“A Better Place for Everyone”

A Buffalo with a unionized hotel sector would be no outlier among pro-labor Democratic cities. According to government statistics, the median full-time pay of hospitality workers who are union members is nearly 27 percent higher than non-union workers.

“Buffalo should be a place where there are many unionized hotel workers,” Bonadonna Jr. says.

Meanwhile, Hyatt workers are keeping the fight going. The union is planning actions in Buffalo for the spring, and it has been meeting with community and political leaders. They’re asking the community to not give money to corporations and developers who retaliate against their workers for organizing.

The union is also waiting on the NLRB decisions around the ULPs and remedial bargaining order, though expectations are hedged given Trump’s anti-union changes to the NLRB.

“We’re hoping for a good outcome, but we can’t place too much faith in the NLRB this day and age,” said Richard Bensinger, the former organizing director of the AFL-CIO who is helping with the Hyatt campaign. “Labor law under Biden was weak at best, but certainly under Trump we can’t treat NLRB decisions as the yardstick by which to measure antiunion behavior.”

Sills is grateful that the Hyatt named him employee of the year. But he’d be even happier, he says, if the hotel respected his and his fellow workers’ right to unionize.

“Having a voice sounds like this really abstract thing,” he says. “But workers have so many good ideas about how to make things better. If we just had a chance to sit across the table from Jemal and put these ideas into a contract, it would make the hotel a better place for everyone.”

The housekeeper Truthout spoke with in her East Side apartment says, more than anything, she wants workers to have more respect at work.

“A person should recognize that you’re human,” she said. “He shouldn’t look at you like you’re disposable, like you’re an animal because you’re an immigrant.”

She says other housekeepers who were scared to support the union, but who continue to feel mistreated, are now asking about it.

“They’re starting to see the importance of the union,” she said.

Derek Seidman is a writer, researcher and historian living in Buffalo, New York. He is a regular contributor for Truthout and a contributing writer for LittleSis.

Truthout is a nonprofit news organization dedicated to providing independent reporting and commentary on a diverse range of social justice issues. Since our founding in 2001, we have anchored our work in principles of accuracy, transparency, and independence from the influence of corporate and political forces. You can make a donation online here or visit our More Ways To Give page for more options.

Spread the word