Los Angeles has more charter schools than any other school district in the nation, and it's a very bad idea.

Billionaires like privately managed schools. Parents are lured with glittering promises of getting their kids a sure ticket to college. Politicians want to appear to be champions of "school reform" with charters.

But charters will not end the poverty at the root of low academic performance or transform our nation's schools into a high-performing system. The world's top-performing systems - Finland and Korea, for example - do not have charter schools. They have strong public school programs with well-prepared, experienced teachers and administrators. Charters and that other faux reform, vouchers, transform schooling into a consumer good, in which choice is the highest value.

The original purpose of charters, when they first opened in 1990 (and when I was a charter proponent), was to collaborate with public schools, not to compete with them or undermine them. They were supposed to recruit the weakest students, the dropouts, and identify methods to help public schools do a better job with those who had lost interest in schooling. This should be their goal now as well.

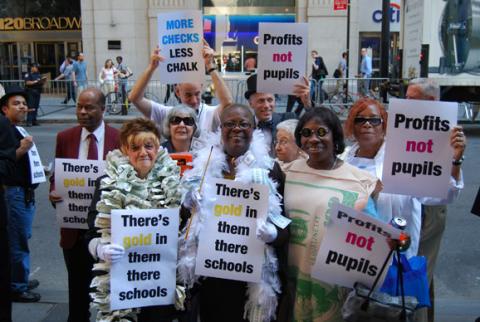

Instead, the charter industry is aggressive and entrepreneurial. Charters want high test scores, so many purposely enroll minimal numbers of English-language learners and students with disabilities. Some push out students who threaten their test averages. Last year, the federal General Accountability Office issued a report chastising charters for avoiding students with disabilities, and the ACLU is suing charters in New Orleans for that reason.

Because they are loosely regulated, charter schools are often neither accountable nor transparent. In 2013, the founders of an L.A. charter with 1,200 students were convicted of misappropriating more than $200,000 in public funds. In Oakland, an audit at the highest-performing charter schools in the state found that $3.8 million may have been misused when the founder hired his other businesses to do work for his charters.

Charter schools are "public" when it is time to claim public funding, but they have claimed in federal court and before the National Labor Relations Board to be private corporations when their employees seek the protection of state labor laws.

In Los Altos, a group of wealthy people opened a boutique charter school for their own children. Parents are asked to donate $5,000 per child each year. Local public school parents consider the charter to be an elite private school, albeit one primarily funded with public dollars.

Of course there are honorable, well-run charter schools that provide an excellent education. This newspaper's editorial board cites independent research that shows students in L.A. charters do better than they would in L.A. Unified schools. But many other studies show that charters in general are no more successful at the task of educating children than public schools if they enroll the same kinds of students.

As large as the gulf can be between charter cheerleading and charter reality, it doesn't represent the greatest danger of these schools. They have become the leading edge of a long-cherished ideological crusade by the far right to turn education into a consumer choice rather than a civic obligation.

Abandoning public schools for a free-market system eviscerates our basic obligation to support them whether our own children are in public schools, private schools or religious schools, and even if we have no children at all.

The campaign to "reform" schools by turning public money over to private corporations is a great distraction from our system's real problems: Academic performance is low where poverty and racial segregation are high. Sadly, the U.S. leads other advanced nations of the world in the proportion of children living in poverty. And income inequality in our nation is larger than at any point in the last century.

We should do what works to strengthen our schools: Provide universal early childhood education (the U.S. ranks 24th among 45 nations, according to the Economist); make sure poor women get good prenatal care so their babies are healthy (we are 131st among 185 nations surveyed, according to the March of Dimes and the United Nations); reduce class size (to fewer than 20 students) in schools where students are struggling; insist that all schools have an excellent curriculum that includes the arts and daily physical education, as well as history, civics, science, mathematics and foreign languages; ensure that the schools attended by poor children have guidance counselors, libraries and librarians, social workers, psychologists, after-school programs and summer programs.

Schools should abandon the use of annual standardized tests; we are the only nation that spends billions testing every child every year. We need high standards for those who enter teaching, and we need to trust them as professionals and let them teach and write their own tests to determine what their students have learned and what extra help they need.

Our nation is heading in a perilous direction, toward privatization of education, which will increase social stratification and racial segregation. Our civic commitment to education for all is eroding. But like police protection, fire protection, public beaches, public parks and public roads, the public schools are a public responsibility, not a consumer good.

[Diane Ravitch is a historian of education. Her latest book is "Reign of Error: The Hoax of the Privatization Movement and the Danger to America's Public Schools."

From 1991 to 1993, she was Assistant Secretary of Education and Counselor to Secretary of Education Lamar Alexander in the administration of President George H.W. Bush. She was responsible for the Office of Educational Research and Improvement in the U.S. Department of Education. As Assistant Secretary, she led the federal effort to promote the creation of voluntary state and national academic standards.

From 1997 to 2004, she was a member of the National Assessment Governing Board, which oversees the National Assessment of Educational Progress, the federal testing program. She was appointed by the Clinton administration's Secretary of Education Richard Riley in 1997 and reappointed by him in 2001. From 1995 until 2005, she held the Brown Chair in Education Studies at the Brookings Institution and edited Brookings Papers on Education Policy. Before entering government service, she was Adjunct Professor of History and Education at Teachers College, Columbia University.]

Spread the word