For the last few years I’ve been writing a scholarly book about Shel Silverstein’s life and work. Yet, after five years of labor, I’ve recently come to realize that my book will very possibly never be published.

Why not? Well, certainly not because there’s a glut of other books about Silverstein. Only one popular biography exists, and I guess if you count the Shel-centric Silverstein and Me: a Memoir, by Silverstein’s lifelong friend, Marv Gold, you could up that number to two. However, these books don’t talk much about the work. A frustratingly small number of scholarly and critical studies of any type put his complex and unconventional life in conversation with his art.

And it’s not because there’s nothing to write about. Most of us know Silverstein for his children’s poetry and picture books (such as Where the Sidewalk Ends and The Giving Tree), but fewer realize he got his start writing gag strips for The Stars and Stripes while serving a tour of duty in Korea. He created decades of work in a variety of genres for Playboy, and he was also an amazingly prolific songwriter (composing hundreds of songs recorded by the likes of Johnny Cash, Lucinda Williams, Gordon Lightfoot, Marianne Faithfull, Loretta Lynn, Dr. Hook and the Medicine Show, Dr. Dog, and My Morning Jacket). Shel authored scores of darkly comic short plays and even wrote a film script with David Mamet (1988’s Things Change).

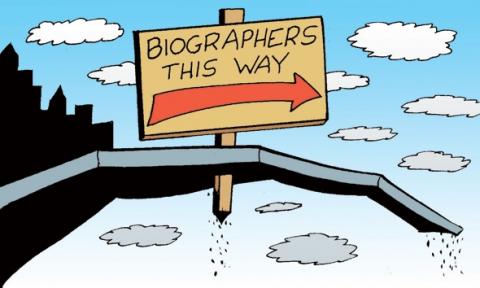

Silverstein’s an important figure, is what I’m getting at. He lived an interesting life, and he produced more than his fair share of aesthetically and commercially successful art. So why has there been so little critical attention paid to such a provocative and prolific character, so little scholarship striving for the Big Picture? And why might my attempt to write this very kind of work potentially never appear in print? Put simply: because of Shel Silverstein’s estate. Because it’s so damned difficult to get permission to quote from his poems and songs, to illustrate claims with reproductions of his art—even a tiny black-and-white reproduction of a comic panel or three or four lines of a song. I’m not the only biographer of an important figure who has this problem. It has to change.

It comes down to this: the Silverstein estate is especially reluctant to give out what’s called “permissions,” the right to quote from (or reproduce parts of) work protected by copyright. Last year an academic journal asked me to obtain permission to reproduce some of Silverstein’s material in an essay of mine they were about to publish. Most of the required images first appeared in Playboy; the magazine gave me an email address belonging to Silverstein’s nephew, who evidently handles this kind of thing for the estate. I wrote this nephew several times, and after a handful of attempts over the course of months, I heard back from a law firm whose name seemed to come straight out of a Shel Silverstein poem: Solheim, Billing, and Grimmer.

Sadly, I can’t reproduce their letter because it’s protected under copyright. (Recipients of letters own the letter, but the content of the letter—or scans of the letter itself—cannot be reproduced without the permission of the letter writer. You can imagine how frustrating this is for biographers.) Still, SB&G’s five-sentence missive is easy to summarize: it forbade me not only from reproducing images for this one article, but from ever reproducing any of Silverstein’s work—song lyrics, poems, images, whatever—in any context. Ever. (Not quite “ever.” Silverstein’s work begins entering the public domain in 2051. Of course, that’s assuming Disney doesn’t have copyright law changed again when Mickey Mouse once more nears the borders of the public domain. Not a great assumption to make.)

Now, I mentioned in my query that I was writing a book—and I mentioned that the book discusses Silverstein’s work for children alongside his work for adults; I also included a copy of another essay I had written on the subject, an essay that doesn’t shy away from the, shall we say, less G-rated details of his life and career: his womanizing, his songs about drugs and venereal disease, his work for Playboy. But I wasn’t asking permissions for the book. I made this clear in the request: I was asking to reproduce only a few images for this one article. And yet Silverstein’s estate decided to muzzle me completely. They closed the letter with these words: “Our clients appreciate your interest in the works of Shel Silverstein and wish you the best of luck in your other future endeavors.” This endeavor, however, they have sunk, and it’s likely to remain unsalvageable as long as they control Silverstein’s copyrighted work.

And so I came up against the hard truth of the literary biographer: It’s crucial to establish friendly relations with the estates of deceased (and more rarely, living) artists whose work is protected by copyright. You see, scholars have to request permission to reproduce more than a few lines of a copyrighted poem or song lyric. Or, more precisely, we don’t have to, but our publishers (largely academic, nonprofit university presses) tend to insist that we ask permission in order to protect themselves from lawsuits. You may have heard of something called “fair use.” One would think fair use was custom built to protect scholars and artists who want or need to reproduce excerpts from copyrighted work in the service of education or art or scholarship—and one would be right. But whether we’re protected or not, most presses prefer to play it safe and make scholars request permission.

This situation is disastrous for serious scholarship for a number of reasons. Instead of simply writing what our research tells us, quoting what we need to quote, scholars are put in the position of hunting down permissions, a process that can take months. More absurdly, it puts our research and our conclusions at the (not so) tender mercies of the subjects of our scholarship (or, worse, the mercy of their estates). If scholars and critics know we need “permission” to quote a few lines of a poem, a few panels of a comic, a verse of a song, we might—and, sadly, too often do—mellow out what might otherwise be more harsh or unsympathetic assessments. We might modify or neglect certain avenues of inquiry, might hesitate, say, to point out that many of Shel Silverstein’s children’s poems first appeared in Playboy, might not dwell on the fact that a beloved author/illustrator of children’s books wrote and performed a song called “Fuck ’em,” a song that includes the lyrics:

Woman come around and handed me a line

About a lot of little orphan kids suffering and dying.

Shit, I give her a quarter cause one of them might be mine.

Yeah, the rest of those little bastards can keep right on crying.

I mean, fuck kids.

We might steer clear of such controversial material for fear a permission request—or a request to read manuscripts, to visit a private archive, to reproduce sections of unpublished material—could be rejected by the estate should our work contravene its opinion about how an author or his work ought to be represented. (Although that five-line excerpt above should be covered by fair use, if this were an academic press and not Slate, that press would more than likely insist I ask SB&G for permission to reproduce it. You can imagine how that would go.)

My professional difficulties with the Silverstein estate are perhaps unusual—flat-out refusal, in perpetuity, with no given reason: that is, a kind of censorship—but it’s an extreme case that illustrates a problem pervasive in the scholarly world. Other scholars have had difficulties similar to mine. Books and articles on Louis Zukofsky, Sylvia Plath, Adrienne Rich, Philip Larkin, and a host of others have died on the vine as a result of persnickety estates (or difficult artists). (Check out Ian Hamilton’s Keepers of the Flame: Literary Estates and the Rise of Biography for some particularly famous examples.) Other books have survived, but were born hobbled by the lack of quotation. (The scholars involved are understandably nervous about publicizing their fights, so forgive me for being vague.) Similarly, scholarship on Disney, Harry Potter, and Star Wars films, as well as comics owned by Marvel and DC, live out their lives on hard drives, never published, or see publication in adulterated form, a shadow of their author's intent, crucial images omitted and replaced by a weird kind of scholarly ekphrasis. And even if scholars get permission, it often comes with a hefty price tag—a fee paid by academics who write for free.

I could wrap up this piece with the obvious analogy of Big Pharma’s influence on medical journals, point you to that essay in the Atlantic that demonstrates how copyrighted works from the midcentury are disappearing into an Orwellian memory hole, or even lament the power Disney has over our legislative bodies, but instead I’ll end with a question and gesture toward an answer: How legitimate can scholarship be, these days, when scholars cannot point to works of art we find interesting or problematic, troubling or provocative, cannot set our commentary beside the texts on which we comment, cannot enter into serious discussions about important works and their writers without asking permission of those selfsame artists or their moneyed interests?

The public perception of scholarship and criticism is shaped by instances where objectivity has failed. Everybody knows stories of novelists reviewing the work of their friends, poetic rivals going after each other in the press, lavishly illustrated encomiums to this or that artist published with the estate’s blessing. The influence of estates on scholarship tarnishes public perception of scholarship, makes it even harder on most scholars, those who strive for objectivity, strive for honest and thorough discussion of works and artists we find important. And these estates, with the power to withhold permission when one writes what they don’t want written—the power to withhold permission simply because the books are selling just fine, thank you, we don’t need a scholar nosing around and upsetting things—these shortsighted estates not only frustrate scholars, like me, but they fail in their role as stewards of the reputations of artists and writers with which they have been entrusted.

So what’s the solution? Sadly, these practices are so deeply entrenched, so natural to writers and presses and their editors and lawyers and, yes, to estate executors (and their lawyers) that sometimes it seems all writers and scholars can do is mutter complaints to friends. If there is a solution, it requires that more scholars speak up. We need to out presses with too-strenuous permission guidelines (like Wayne State UP, who published my first book: a hard-working publisher of integrity who nonetheless should stand up for academic freedom, for the rights of the scholars and critics who write for them). We need to write essays like the one you’re reading, explain to the public how unreasonable estates can be about policing what’s said about the artists whose legacy they ostensibly curate.

What we have here—if you’ll forgive the military metaphor—is but one front in a larger war against the rigorous analysis of fact. It’s part of a war against the presentation of evidence, a war against thoughtful, good-faith argumentation and conscientious debate. It’s another front in the larger war against truth. Which side are you on?

A poet and a scholar, Joseph Thomas is a professor at San Diego State University.

Spread the word