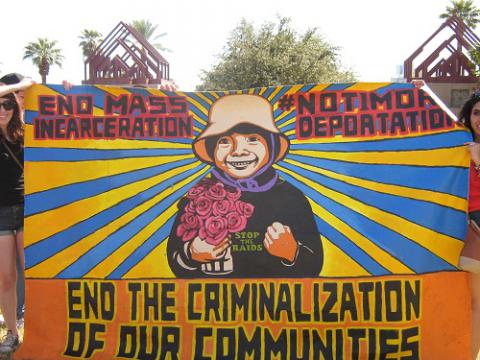

Criminalization of Immigration Causes Warehousing of Thousands in Inhumane Privatized Prisons

Thousands of immigrants are locked up in a shadow private prison system as a result of the criminalization of immigration over the past decade, according to a recent report by the American Civil Liberties Union.

The 101-page report, “Warehoused and Forgotten: Immigrants Trapped in Our Shadow Private Prison System,” is a stinging indictment of prison privatization in the United States.

Immigrants incarcerated in privatized facilities receive poor medical care, live in overcrowded conditions, don’t have ready access to legal representation, lack education and vocational training opportunities, and are often housed far away from their families.

The act of illegally crossing the border into the United States used to be treated as a civil offence resulting in deportation. But the decision of the federal government several years ago to treat illegal crossings as a criminal offence has led a mass incarceration of immigrants in segregated facilities.

Illegally entering the country is a federal misdemeanor punishable by up to six months in prison. Re-entering the United States after deportation is a felony that can lead to two years in prison for a person without a criminal record. People with serious criminal records who re-enter the country can be locked up for 20 years.

The criminalization of immigration is enriching for-profit companies that operate privatized facilities. The privatized prisons aren’t subject to many of the policies and regulations of government-run prisons and are therefore largely unaccountable to outside oversight.

“The tipping point came in 2009, when more people entered federal prison for immigration offenses than for violent, weapons, and property offenses combined—and the number has continued to increase every year,” the report says. That year, the Federal Bureau of Prisons awarded contracts to two contractors to run two prisons in California and New Mexico housing up to 7,500 low-security, non-citizens inmates.

On a daily basis in 2012, the Bureau of Prisons held 23,700 people convicted of immigration offences. The number of people charged with federal immigration offenses increased by 367 percent from 2003 to 2013, when 97,384 people were prosecuted.

Foreign federal prisoners are mostly sent to thirteen “Criminal Alien Requirement” (CAR) prisons. Today, more than 25,000 “low-security criminal aliens” are locked up in these prisons. The ACLU report, released in June, focuses on the five CAR prisons in Texas.

The CAR facilities, which are among a group of federal prisons operated by for-profit companies instead of the Bureau of Prisons, exclusively house non-citizens. They have lower security requirements than medium- and maximum-security institutions run by the bureau.

Shocking Abuse and Mistreatment

“Our investigation uncovered evidence that the men held in these private prisons are subjected to shocking abuse and mistreatment, and discriminated against by BOP polices that impede family contact and exclude them from rehabilitative programs,” the report says.

Among the report’s findings:

• Private prison contracts provide incentives that result in overcrowding.

The contracts reviewed by the ACLU have occupancy quotas that require facilities to operate at least 90 percent capacity and provide incentives to house additional prisoners until the rate reaches 105 percent.

The bureau’s contracts for the Texas facilities require the five prisons to use 10 percent of their bed space for isolation cells—which is double to rate in government-run prisons. The requirement leads private prisons to put prisoners into isolated cells for minor and even bogus infractions, allowing additional detainees to be housed in the low-security space.

• Medical understaffing and cost-cutting limits prisoners’ access to emergency and routine medical care. In one facility, prisoners reported that a single doctor was responsible for attending to 2,000 inmates.

• Prisoners live in overcrowded and squalid conditions.

At the Willacy Count Correctional Center in Texas, for instance, prisoners live in Kevlar tents in which 200 inmates sleep on bunk beds spaced only a few feet apart. Detainees report that the tents are dirty and filled with insects. Foul odors come from toilets that frequently overflow.

“Sometimes it smells,” a prisoner told the ACLU. “They just don’t have enough space for all of us here. Sometimes it makes me go crazy.”

“[Our families] don’t know that we suffer, that we’re not treated with respect, or that we sometimes lack food or blankets,” said Vicente, a prisoner at the Willacy. “We don’t tell our families. I just don’t want my kids to see me like this.”

• Many prisoners have family ties in the United States, but they have far more limited access to drug rehabilitation and work opportunity than U.S. citizens in other federal prisons.

“I had the idea: I have three years,” said Jaime, a prisoner at Big Spring Correctional Center in Big Spring, Texas. “I will do something so I have something to make of myself…. But there’s nothing to do here.”

A Multi-Billion Dollar Business

Mass incarceration has fueled the growth of the private prison industry in the United States.

The “War on Drugs” and harsher sentencing led the U.S. prison population to increase by 700 percent between 1970 and 2009—faster than population growth and the crime rate. The United States has 5 percent of the world’s population but accounts for 25 percent of the world’s prisoners.

The multi-billion-dollar private prison industry has taken advantage of the explosion in the prison population.

From 1990 to 2009, the private prison industry grew by more than 1,600 percent.

In 2012, the three corporations that operate the 13 CAR facilities—Corrections Corporation of America, the GEO Group (GEO) and MTC—reported nearly $4 billion in revenue, according to the ACLU report. The political action committees and employees of the three companies have spent more than $32 million on federal lobbying and campaign contributions since 2000.

The companies operate a “shadow prison” that is largely free of public scrutiny. The Corrections Corporation of America has spent some $7 million since 2007 in a successful lobbying campaign against legislation that would subject it to the same open-records obligations as facilities operated by the federal government.

The Bureau of Prisons monitors the facilities, but it rarely cancels contracts, even in egregious circumstances, according to the ACLU report.

The bureau, for instance, has renewed its contracts with the GEO Group to run the Reeves County Detention Center in Pecos, Texas, where detainees make up nearly half of the local population, despite prisoner protests of inhumane living conditions, two major uprisings and negative reports by BOP monitors.

“In addition to failing to cancel contracts in response to underperformance, BOP policies turn a blind eye to prisoner grievances from these private prisons,” the report says.

The privatized facilities apparently lack the uniform administrative policies of government-run prisons that determine the procedures for prisoners to voice grievances.

Geographic isolation, barriers to access to attorneys and advocacy organizations, and legal barriers to accountability limit the prisoners’ ability to receive help, according to the ACLU.

“Prisoner after prisoner described how BOP’s decisions to incentivize overcrowding and abuse of extreme isolation, turn a blind eye to inadequate medical care and other forms of neglect, and deny rehabilitative programming have created dangerous, squalid, and tense conditions in these private prisons,” concludes the report, which calls for a federal investigation of the private prisons and a return of immigration enforcement to civil immigration authorities. “And despite multiple protests and uprisings, little seems to change.”

“They don’t take us seriously,” said Dominic, a prisoner in isolated confinement who spends 23 hours a day in cold cell at Big Spring. When the ACLU interviewed him, he continued to suffer from a severely injured wrist three months after an emergency room physician said he needed surgery.

“It’s all money for them,” Dominic said.

Spread the word