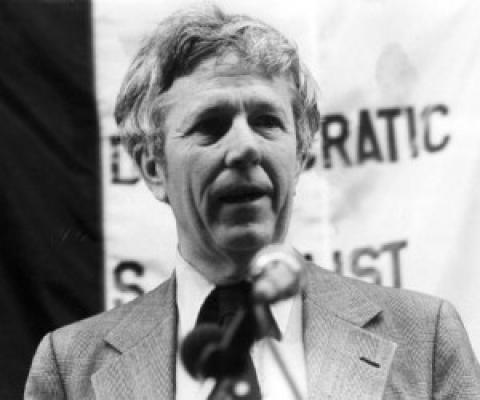

In a lifetime of political engagement, Michael Harrington must have given ten thousand speeches, and of those, probably a thousand in New York City, where he had made his home since his arrival in 1949, age 21. He gave his final speech in the city 40 years later, in May 1989. Suffering from the cancer of the esophagus that would end his life in less than three months, he spoke that day to reporters and editors from the city’s union press.

Dinah Leventhal, a 22-year-old activist, was in attendance. She was about to take on the job of youth organizer for Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), the socialist group that Harrington helped found and led, and welcomed the chance to speak with him for a few minutes afterward. Mike reminisced about his own days as a young socialist organizer in the 1950s. “He said,” she recalled, that “he had felt an incredible degree of freedom and learned so much in those years"

He said I should make the most of it, being an organizer and traveling around, getting to see the country and getting to know what the country was all about. He really loved this country, and thought that you had to love the country to be a radical, to be a socialist, and to want to change it.

Over the years, Mike met and worked with many important and famous people, including Dr. Martin Luther King, United Auto Worker president Walter Reuther, Ms. Magazine founder Gloria Steinem, U.S. senator and presidential candidate Robert Kennedy, and Prime Minister Olof Palme, leader of Sweden’s ruling Socialist Party, to name but a few. The publication in 1962 of his landmark study of poverty, The Other America, helped spark the Johnson administration’s War on Poverty. He had another best-seller in 1972 with the unlikely title of Socialism, which sold over 100,000 copies in paperback and influenced many readers with its argument that the “real Karl Marx” was a radical democrat, not a would-be dictator. His last book, Socialism: Past and Future, came out shortly before his death. He was an editor of Dissent, a commentator on National Public Radio, a frequent contributor to leading opinion magazines like the Nation and the New Republic. As a public intellectual and a moral tribune, in the 1970s and 1980s, he had few equals on the left, or indeed across the political spectrum. Harrington, Senator Ted Kennedy would write, “has made more Americans more uncomfortable for more good reasons than any other person I know.”

Perhaps Mike’s greatest political impact was on several generations of young radicals coming of age between the 1950s and the 1980s. He spoke before all kinds of audiences, in churches and union halls, and won applause from listeners who had probably never heard a socialist before. But he was most in his element when speaking on college and university campuses. He liked young people; he knew how they thought; he could reach and inspire them. He was, he liked to joke as the decades turned and his hair grew grayer and then white, the nation’s “oldest young socialist” and “a closet youth.”

Born in 1928 in St. Louis, the only child of middle-class parents of sturdy Irish Catholic background and staunch Democratic sympathies, educated at Holy Cross (which he entered at age 16, and graduated from at age 19), Yale Law School (acing his first year, and then dropping out when he decided the law wasn’t for him), and the University of Chicago (earning a master’s degree in English literature in 1949), he then moved to New York City to become a writer. Somewhere along the line he had developed vaguely leftish sympathies, but without joining any radical groups. But in 1951 he was drawn to Dorothy Day’s anarchist-pacifist Catholic Worker movement, and moved into the group’s “House of Hospitality” on Chrystie Street on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. There, with other volunteers, he worked in the soup kitchen (which catered to the homeless alcoholics who crowded the nearby Bowery District), wrote for and helped edit the Catholic Worker newspaper, and joined sparsely attended picket lines protesting the Korean War, his unmistakably Irish face and name confounding the NYC police department’s Red Squad, which monitored such events.

Mike remained indelibly Irish, but was about to shed his Catholicism (his religious faith wavering even before he joined the Catholic Worker). In 1952, he departed Chrystie Street, moved to Greenwich Village, and joined the Young People’s Socialist League (YPSL), youth affiliate of the battered remnant of the once-vibrant Socialist Party, founded by Eugene Debs at the turn of the century, and led for the past several decades by Norman Thomas. He was in select company: YPSL counted 134 members nationwide in 1952. And it was about to get smaller, because Mike joined a group that split away to form a new and even fringier youth group, the Young Socialist League (YSL), whose adult mentor was a former Trotskyist with a long history of radical factionalism named Max Shachtman, leader of the Independent Socialist League, formerly the Workers Party, formerly a split-off from the Socialist Workers Party, and so on. The “Shachtmanites,” as they were called, were ferociously anti-Stalinist (not entirely a bad thing), but also ferociously sectarian (an entirely bad thing). Despite occupying the lefter-than-thou margins of an already marginal socialist movement, Shachtman attracted some talented lieutenants (Irving Howe had been one until he left the ISL to found Dissent in the early 1950s); Mike was the latest, and perhaps most talented, catch.

In time, the Shachtmanites returned to the Socialist Party (and, in Mike’s case, the Young People’s Socialist League). As YPSL national organizer in the late 1950s he hitch-hiked back and forth across the country, visiting campuses from Brandeis to the University of California at Berkeley, building YPSL chapters, and, more important, detecting the stirrings of a movement he started to refer to as a “New Left.” Tom Hayden and other young activists who were in the process of creating their own campus group (smaller than YPSL at its inception) called Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) were among those Harrington influenced. Mike famously wound up quarreling with Hayden and other SDSers at their founding convention in Port Huron, Michigan, in 1962 (not having put aside all the sectarian instincts of the early 1950s) – a rift he deeply regretted.

In the next year, after a review of his study of poverty, The Other America, catapulted the subject into policy-making circles, Mike became famous (and incredibly busy) as “the man who discovered poverty.” He was less involved with the student movement (although still a frequent speaker on college and university campuses). In the later 1960s, as the war in Vietnam escalated and radicalized a generation, and as the organized New Left, particularly SDS, embraced confrontational tactics and revolutionary rhetoric, Mike found it increasingly difficult to connect with the young campus activists. But he tried. At a conference of socialist leaders in 1967, Mike cautioned against strident denunciations of the New Left: “They will make mistakes, but they are the people – when things get better – that I’ll have to work with.”

In 1973, with the old SP in ruins, Mike and others created a new group, the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee (DSOC), which soon developed a vibrant Youth Section. In 1982, DSOC merged with the New American Movement (NAM), which had been founded some years earlier by former New Leftists. The merged organization becoming Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), with its own Youth Section, eventually renamed the Young Democratic Socialists (YDS).

Mike religiously attended the winter and summer conferences sponsored by DSA’s Youth Section. The last time he did so was in February 1989. In a speech to the students in attendance he acknowledged that some of them would pay their DSA dues for a year or so (“God bless you”) then move on to other things, and “probably remain, at least, a good liberal.” But to those who would wind up staying in the movement for the long term, he had special words of encouragement, drawing on nearly four decades of experience:

This movement should enrich you. This movement should allow you to lead a different kind of life. This is not a burden. At its best this is a movement of joy….

Like his predecessors Eugene Debs and Norman Thomas, Mike Harrington believed that to waken the conscience and change the consciousness of a nation, one had to be prepared to build an organization, start a publication, speak in a thousand halls to crowds of hundreds, or scores, or tens, if necessary, recruiting comrades from those converted by the sound of one’s voice and the strength of one’s arguments. It was, and remains, a heroic vision.

Maurice Isserman, a charter member of DSA, is the author of The Other American: The Life of Michael Harrington (2000), from which this essay is adapted

Spread the word