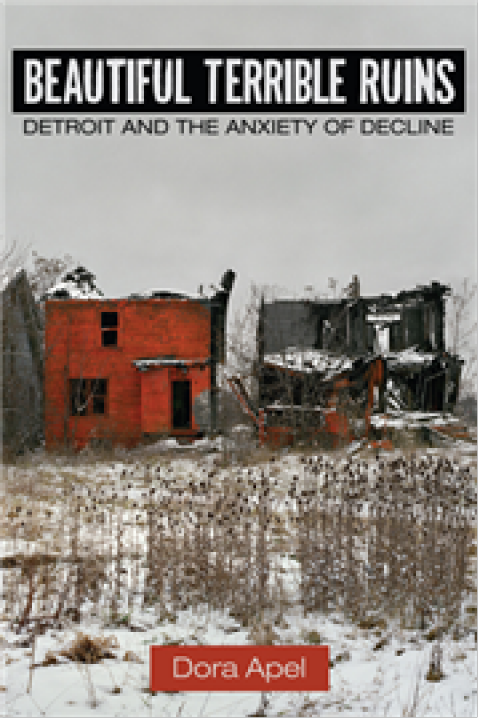

Beautiful Terrible Ruins

Detroit and the Anxiety of Decline

Dora Apel

Rutgers University Press

Paper. ISBN: 978-0-8135-7406-6

By Scott McLemee

In 2011, Paul Clemens, a writer from Detroit published an up-close and personal look at deindustrialization called Punching Out: One Year in a Closing Auto Plant. It recorded the year he spent on a work team hired to dismantle and gut one of the city’s remaining factories. I wrote about the book when it came out, and won’t recycle anything here, but recall a few paragraphs expressing a particular kind of frustration that a non-Detroiter can only sympathize with, not really share.

The cause was a tendency by outsiders – or a subset of them at any rate – to treat the city’s decline as perverse kind of tourist attraction or raw material for pontification. Clemens had lost all patience with arty photographs of abandoned buildings and pundits’ blatherscate about the “creative destruction” intrinsic to dynamic capitalism. He also complained about the other side of the coin, the spirit of “we’re turning the corner!” boosterism. “No Parisian is as impatient with American mispronunciation,” he wrote, “no New Yorker as disdainful of tourists needing directions, as is a born-and-bred Detroiter with the optimism of recent arrivals and their various schemes for the city’s improvement.”

Dora Apel, a professor of art history and visual culture at Wayne State University, has, in effect, gathered everything that dismays and offends Clemens between the covers of Beautiful Terrible Ruins: Detroit and the Anxiety of Decline (Rutgers University Press).

She calls Detroit “the quintessential urban nightmare in a world where the majority of people live in cities.” But nightmare imagery can be seductive, making Detroit “a thriving destination for artists, urban explorers, academics, and other curious travelers and researchers who want to experience for themselves industrial, civic, and residential abandonment on a massive scale.”

That lure is felt most keenly by people who, after the “experience,” enjoy the luxury of going home to someplace stable, orderly, and altogether more pleasant. It’s evident Apel finds something ghoulish about taking pleasure from a scene of disaster, “feeding off the city’s misery while understanding little about its problems, histories, or dreams.” But the aesthetic appeal of ruins – the celebration of old buildings crumbling picturesquely, of columns broken but partly standing, of statuary fractured and eroded by time –- goes back at least to the 18th century, and it can’t be reduced to mere gloating. The author makes a brief but effective survey of “ruin lust,” a taste defined by “the beautiful and melancholic struggle between nature and culture,” as well as the feelings of contrast between ancient and modern life that ruins could evoke in the viewer, in pleasurable ways. She also points out how, in previous eras, this taste often involved feelings of national superiority, as with well-off travelers enjoying the sight of another country’s half-demolished architecture. (At least a tinge of gloating, in that case.)

It’s not difficult to recognize classical elements of the ruins aesthetic as "The Tree" by James D. Griffioen. One of a number of images reproduced in the book, Griffioen took the photograph in the Detroit Public Schools Book Depository, in which a sapling has taken root in the mulch created by a layer of decomposing textbooks – an almost schematic case of “the beautiful and melancholic struggle between nature and culture.” But Apel underscores the differences between the 21st century mode of “ruination” and the taste cultivated in earlier periods. For one thing, ““modernist architecture refuses the return of culture to nature in the manner of ancient ruins in large part because the building materials of concrete, steel, and glass do not delicately crumble in the picturesque way that stone does.”

More importantly, though, the fragments aren’t poking up from some barely imaginable gulf in time and culture: Detroit was, in effect, the world capital of industrial society within living memory. In his autobiography published in the early 1990s, then-Mayor Coleman Young wrote: “In the evolutionary urban order, Detroit today has always been your town tomorrow.” The implications of that thought are considerably more gloomy than they were even 20 years ago. One implication of imagery such as "The Tree" is that it’s not a reminder of the recent past so much as a glimpse at the ruins of the not too distant future.

Photography is not the only cultural register in which the fascination with contemporary ruins makes itself evident: There are “urban exploration,” for example: a subculture consisting (it seems) mainly of young guys who trespass on ruined property to take in the ambience while also enjoying the dangers and challenges of moving around in collapsing architecture. Apel also writes about artists in Detroit who have colonized depopulated areas both to reclaim them as living space and to incorporate the ruins into their creative work.

The effects are not strictly local: “the borders between art, media, advertising, and popular culture have become increasingly permeable,” Apel writes, “as visual imagery easily ranges across these formats and as people produce their own imagery on websites and social media.” And the aestheticized ruination of Detroit feeds into a more widespread (even global) “anxiety of decline” expressed in post-apocalyptic videogame scenarios, survivalist television programs, zombie movies, and so on. Not that Detroit is the inspiration in each case, but it provides the most concrete, real-world example of dystopia.

“As the largest deteriorating former urban manufacturing center,” Apel writes, contemporary Detroit is a product of an understanding of society in “rights are dependent on what people can offer to the state’s economic well-being, rather than vice-versa,” and “the lost protection of the state means vastly inadequate living conditions and the most menial and unprotected forms of labor in cities that are divested of many of their social services and left to their own devices.”

Much of the imagery analyzed in Beautiful Terrible Ruins seems to play right along with that social vision. The nicely composed photographs of crumbling buildings are usually empty of any human presence, while horror movies fill their urban landscapes with the hungry undead -- the shape of dreaded things to come.

Scott McLemee is the Intellectual Affairs columnist for Inside Higher Ed.

Spread the word