The New Yorker recently attempted to explain two “populists” running for president, the only candidates generating huge and enthusiastic audiences. Instead, the article’s snide tone reflected the nearsightedness of cosmopolitan elites. Both candidates were mislabeled as “populist.” Bernie Sanders is a democratic socialist; Donald Trump is a trash-talking billionaire. But the magazine also mangled the true historical meaning of populism.

The writer seemed to be channeling Richard Hofstadter, the Columbia historian who back in the 1960s famously put down populism and other rebellious movements as “the paranoid style in American politics.” People are irrational, Hofstadter explained, driven by delusional fears and conspiracy theories. Not to be trusted with governing power.

Class condescension is as old as American democracy and is back in vogue this season, thanks mainly to the plutocrat with big hair. Only, Donald Trump turned “populist” anger upside down. He’s a super-rich guy ridiculing the “stupid” people in government and bragging about how he and his fellow billionaires buy politicians to get free stuff from government. Sanders, meanwhile, is plowing a parallel furrow of dissent—a substantive and serious program for reform.

But neither fits the label “populist” because they are both working within the established order. By definition, populism requires plain people in rebellion, organizing themselves to go up against the reigning powers. Major pushback from fed-up people is not present—not yet anyway—but the great disturbances already roiling party politics suggest that the political status quo is vulnerable to more upheavals, particularly if timidity and stalemate continue to suppress meaningful change.

It depends, first, on whether the 2016 results promise real changes in economics and social equity and/or convince people they have to dump both parties and attempt power-seeking politics of their own. This is a tender moment for the two-party system.

Elites naturally fear popular uprisings, but rebellion can be good for democracy. Even if they fail, self-generated citizen insurgencies can ventilate the musty corridors of government and compel governing parties to change or die. A century ago, the original Populists provoked fright and ridicule in establishment circles on a far more threatening scale. We are not there yet. But don’t count it out if timidity wins the election next year and politics continues to run away from fundamental questions.

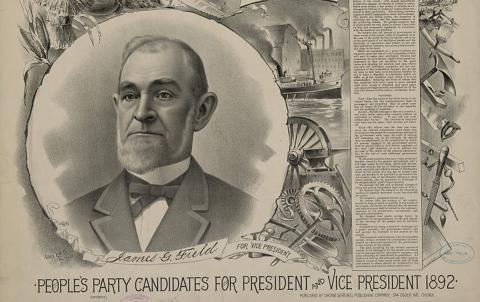

The People’s Party in the last decades of the 19th century was self-organized by scattered groups of distressed farmers. It grew rapidly across the South and West to oppose the powerful forces—banks, railroads, industrial corporations—destroying small, independent producers. The farmers realized the federal government was an active accomplice in their economic destruction. There was nothing delusional about their alarm and anger. It was driven by a ruinous deflation of farm prices for three decades—hard money that rewarded capital and crushed producers.

The agrarian revolt set out audaciously to win power by winning elections—electing Populist governors, representatives, and senators—hoping ultimately to elect the People’s President. They failed, of course, but their legacy was profound. These self-taught citizens developed original ideas for governing the economy, business, and banking. They envisioned a central bank to regulate money and credit that would advance equality, serving people and producers rather than the fortunes of New York bankers. The Populist vision was the road not taken.

The New York Times called them “slime.” (This magazine was pretty bad too, as The Nation’s 1896 attack on William Jennings Bryan shows.) It denounced their proposal as “one of the wildest and most fantastic projects ever seriously proposed.” Yet years later, John Maynard Keynes saluted the American Populists as “a brave army of heretics.” They failed to gain power, but Keynes recognized that their economic analysis anticipated his own. Many of the original Populist proposals were eventually enacted as New Deal reforms.

For the true history, read Lawrence Goodwyn’s Democratic Promise: The Populist Moment in America. The book profoundly altered my understanding of American history and democracy (the excellent shorter version, widely available in paperback, is titled The Populist Moment: A Short History of the Agrarian Revolt in America). Goodwyn’s account provides powerful rebuttal to pessimism and resignation. His unsentimental narrative keeps alive the possibility of deep structural reforms in politics and government.

Democratic Promise puts people back at the center of the story—ordinary people who tried, against all odds, to act like self-directed citizens, actively participating in self-government. Goodwyn suggested that authentic democracy remains possible—not easy or assured, only possible—if people rediscover their voice and potential power.

In modern political culture, the idea of this deeper democracy has been hollowed out, obliterated. The promise endures, insofar as we have regular elections to select officeholders, but that ritual normally does very little to alter actual power relationships. And people know this.

Most Americans are reduced to the passive role of spectators, fans, groupies. Or they are persuaded not to bother with politics. An elaborate class of professional technicians has taken charge of electoral politics—campaign managers and advertisers, pollsters, fundraisers, crowd organizers. These professionals, one could say, manage the passions or passivity of voters. They shape the content of what citizens know—and shape their ignorance too.

The process of manipulating the electorate is enormously expensive, and mostly paid for by private donations. Donors naturally expect to influence the content of the messages, so campaigns are nearly always biased in favor of moneyed interests and affluent citizens. The ultimate purpose of campaigns is thus not educating citizens; it is electing or defeating politicians. The result of this narrow-form democracy is the steadily shrinking electorate. Voters who stay home on Election Day are now by far the “largest” political party.

The critical claim in Goodwyn’s analysis is that ordinary people are both capable of participating more directly in self-government and that their engagement is necessary for a genuinely functioning democracy. Otherwise, politics produces a closely held management system with control concentrated at the top. It makes distant decisions too opaque for ordinary citizens to understand or influence, much less control. This deformity roughly resembles our current conditions. Governing elites typically fault the people for their ignorance, and many discouraged citizens internalize the blame.

But Goodwyn insisted that ordinary people, though discouraged from active citizenship, have essential knowledge—knowledge they haven’t learned from books or newspapers. Their knowledge is crucial for balanced self-government. Because ordinary Americans, regardless of status or education, know things the authorities did not teach them. They frequently know things that contradict the governing experts, and they learn them before elected representatives do.

Where do people get this distinctive knowledge? From life itself, as Goodwyn explained. Of course, people are fallible and prone to error, false enthusiasm, and fears. But so are elected politicians. So are the corporate CEOs and investment bankers, including the ones who led the country over a cliff in 2008 and crashed the middle class.

The popular anger exploding in the run-up to 2016 baffled press and political leaders. They would not have been surprised if they had listened more respectfully to the broad ranks of citizens during the past three decades. Working people knew the “American dream” was falling apart. They knew because it was happening to them. They told their stories in great detail to anyone who would listen (as a young reporter I heard those stories from auto workers, steel workers, machinists, debt-burdened families, and other victims, trying to hang on and losing the struggle).

With brave exceptions, politicians in both parties turned their backs on the cries of distress. Learned economists assured political leaders that what working people saw happening in their neighborhoods wasn’t the real story. Over time, they predicted, prosperity would reach everyone and people would agree that deindustrialization was a good thing, a necessary evolution in the economy. It didn’t happen, and neither party has come clean on its failure.

I think that’s where the anger comes from. There is widespread feeling across ideological and partisan divides not only that government failed to ensure economic prosperity and security but also that both political parties denied or ignored what average working stiffs knew and were trying to tell the politicians. Many believe they were betrayed, that the politicians lied.

Modern government lost its sense of balance and credibility for many reasons, but partly because authorities distanced themselves from the common-sense and popular knowledge of ordinary Americans. This disconnect permeates government and politics, and it’s not always due to corporate greed or corruption. Sometimes, it is due to plain ignorance.

It’s true that we have not arrived at a new “populist moment”—not yet. But the political situation looks combustible, and perhaps more promising than the usual cynicism and resignation will recognize. Could citizens come out of their passivity and restart the fight for authentic self-government? Sounds fanciful, I know, but consider this: If the original Populists could organize millions to overcome their handicaps, people should be able to do the same now. After all, the Populists didn’t even have telephones, much less e-mail.

We are already deep into a stormy new era of democratizing technologies—people are getting the power to control their own communications—and inventive new channels are flowing freely from citizens themselves.

This new condition potentially destabilizes the old politics. I think it is a major factor in generating the dizziness of this election season. Among other things, it drastically reduces the cost of making political connections, of organizing across long distances and social divisions. That itself could become an insurrectionary virtue. It might even dilute the political domination of the 1 Percent, the corporations and billionaires.

I see possibilities for meaningful unrest ahead.

Copyright c 2015 The Nation. Reprinted with permission. May not be reprinted without permission. Distributed by Agence Global.

Please support our journalism. Get a digital subscription to The Nation for just $9.50!

Spread the word