Global Left Midweek – January 17, 2024

Portside

“I knew that I had come from this very dark place — I was abhorrent to society,” said Michelle Jones, a Ph.D. candidate at N.Y.U. who was released from prison in August after serving 20 years. “But for 20 years, I’ve tried to do right, because I was still interested in the world, and because I didn’t believe my past made me somehow cosmically un-educatable forever.”

“I knew that I had come from this very dark place — I was abhorrent to society,” said Michelle Jones, a Ph.D. candidate at N.Y.U. who was released from prison in August after serving 20 years. “But for 20 years, I’ve tried to do right, because I was still interested in the world, and because I didn’t believe my past made me somehow cosmically un-educatable forever.”

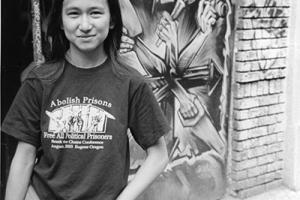

When we think of prison protest, what comes to mind? That list would include the Attica uprising, George Jackson, struggles of the Angola 3 activists, the 2013 California prison hunger strike and other crucial resistance - mostly organized by incarcerated men. Often, organizing work done by incarcerated women goes wholly unrecognized. In her book, Resistance Behind Bars: The Struggles of Incarcerated Women, Victoria Law focuses on women prisoners activism.

When we think of prison protest, what comes to mind? That list would include the Attica uprising, George Jackson, struggles of the Angola 3 activists, the 2013 California prison hunger strike and other crucial resistance - mostly organized by incarcerated men. Often, organizing work done by incarcerated women goes wholly unrecognized. In her book, Resistance Behind Bars: The Struggles of Incarcerated Women, Victoria Law focuses on women prisoners activism.

Spread the word