“There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at the typewriter and bleed.”

—Ernest Hemingway

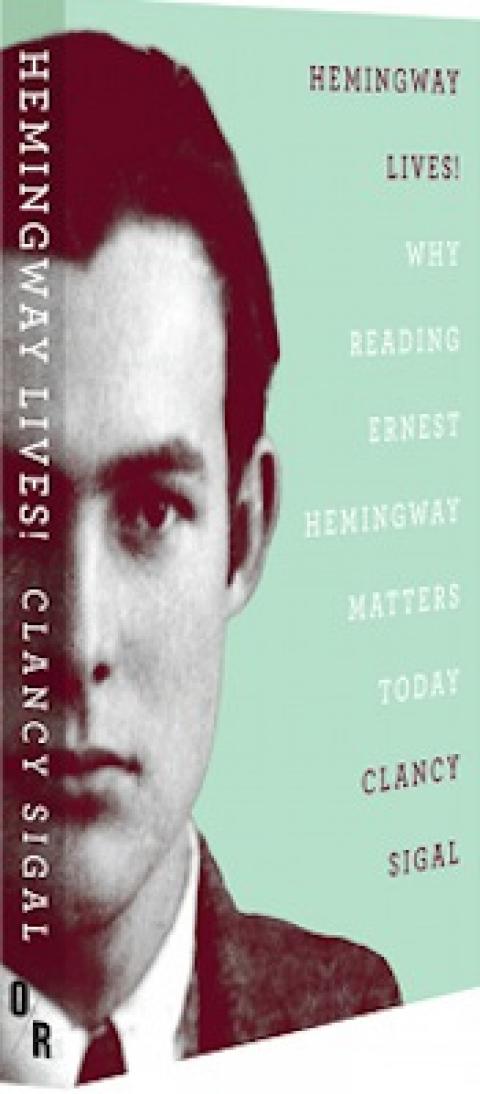

Of all the celebrated male novelists inhabiting America’s literary pantheon, none of them (not Hawthorne or Twain or Steinbeck or Fitzgerald or Faulkner) have a more glamorous persona, a more readily identifiable writing style or, for that matter, a more recognizable face, than the bearded, middle-aged Ernest Hemingway.

Moreover, ever since Hemingway’s death by suicide, in 1961 (his family had a tragic history of multiple suicides), there have been, literally, hundreds of books, articles and monographs written about him. Hemingway’s life and literature have been picked over by every manner of acolyte, academic, professional biographer, motivated layman, and literary Boy Scout to come down the pike. That being the case, why do we need another book on him?

The answer is that, with Hemingway Lives!, noted screenwriter and novelist (and frequent CounterPunch contributor) Clancy Sigal not only presents us with something entirely fresh and revealing, he hits the trifecta. This compact book is thought-provoking, packed with useful information (some of it standard bio material, but much of it wonderfully idiosyncratic), and is lively enough to be described, accurately and without exaggeration, as an old-fashioned “page-turner.”

Ernest Hemingway’s life is presented chronologically, beginning with his birth (in 1899) and childhood in Oak Park, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago. Not surprisingly, as a boy he developed a love for rigorous outdoor activities such as hunting and fishing—activities he embraced all his adult life. After high school, to the disappointment of his parents, young Ernest chose not to attend college. Instead, he landed a job as a newspaper reporter for the Kansas City Star, a decision that Hemingway scholars maintain is what set him on the path to becoming who he became.

It was at the Star where he learned to express himself in those short, economical sentences that so define his literary style. Short, concise, powerfully evocative sentences. No redundancies, no sugary flourishes, nothing superfluous, nothing ostentatious. In fact, in an early chapter, Sigal treats us to a sample of Hemingway’s newspaper copy, written when he was 18 years old. Taken from a Kansas City Star item called, “At the End of the Ambulance Run,” we see undeniable evidence of early “Hemingwayese.”

The night ambulance attendants shuffled down the long, dark corridors at the General Hospital with an inert burden on the stretcher. They….lifted the unconscious man to the operating table. His hands were calloused and he was unkempt and rugged, a victim of a street brawl near the city market. No one knew who he was, but a receipt, bearing the name George Anderson, for $10 paid on a home out in a little Nebraska town, served to identify him.

The surgeon opened the swollen eyelids. The eyes were turned to the left. “A fracture on the left side of the skull,” he said to the attendants who stood about the table. “Well, George, you’re not going to finish paying for that home of yours.”

War, personal nobility, physical courage, and overcoming adversity were among the dominant themes in Hemingway’s writing. Accordingly, the idealistic Hemingway quit the Star after seven months and, in 1918, lured by World War I, volunteered as a Red Cross ambulance driver in Italy, having been turned down for military service due to poor eyesight (one of his eyes was defective). In Italy he was close enough to the front to be seriously wounded by an exploding mortar shell.

The years following Italy were auspicious. In 1921, Hemingway moved to Paris, where he was not only influenced by the “modernist” atmosphere of the city’s art colony, but where, at age 22, he fell in love and

married Hadley Richardson, his first of four wives. In 1926, Hemingway published his debut novel, The Sun Also Rises, which got a rousing reception. That book put him on the map. At age 27, the ambitious young novelist was off and running.

Looking back on it, it’s hard to believe that a man of letters could have lived so exciting and eventful a life. It’s almost as if Hemingway were a character in one of his own adventure novels. There were the Paris years, his second novel, A Farewell to Arms, in 1929 (which made him financially secure), the birth of a son, Jack, a divorce from Hadley, another marriage, this one to Hadley’s best friend, the wealthy Pauline Pfeiffer; leaving Paris, moving to Key West, his father’s suicide, and, in 1933, the safari to Africa with wife Pauline.

And when civil war broke out in Spain in 1937, Hemingway immediately traveled there and joined up with the anti-fascist Republicans (his novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls, is based on the Spanish Civil War). Then there was another divorce, another new wife (the noted journalist Martha Gellhorn, portrayed by Nicole Kidman in the recent HBO movie), more children, the move to Cuba, submarine hunting on his private boat, earning the antipathy of J. Edgar Hoover, and then, in 1944, landing with D-Day troops in France. Even if the man had never written a single word, his non-literary life would’ve made one heck of a movie.

Although Sigal addresses Hemingway’s many personal demons and character flaws (the alcohol consumption, the life-long bouts of depression, the jealousies, anxieties, infidelities, et al) straightforwardly and honestly (including Hemingway’s vulgar insensitivity to race and ethnicity), he avoids the temptation to over-emphasize or wallow in the lurid details. It simply isn’t that kind of book.

There’s an agreeable amount of boilerplate biographical material mixed with a generous serving of idiosyncratic personal anecdotes. For instance, Sigal notes that as a young boy, Ernest’s mother, Grace, regularly dressed the poor kid and his older sister as boy-girl twins. This macho, uber-masculine icon used to wear frilly skirts and dresses, a circumstance which, as Sigal wryly notes, provided the Freudians with enough gas to fly to the moon.

In another anecdote, the 19-year old Ernest wrote his family from New York City (where he’d stopped on his way to Italy), announcing that he was engaged to be married to Mae Marsh, the famous silent screen movie star. That must have been a real thrill for the folks back home in Oak Park. Years later, Ms. Marsh, now an elderly woman, said that she regretted not having met Hemingway in real life. Apparently, young Ernest had already discovered a flair for “fiction.”

Arguably, the most impressive part of Hemingway Lives! is the “scholarly” part, the purely “literary” part, the part where Sigal steps up to the plate and nimbly summarizes each of Hemingway’s novels and short stories. It’s an impressive performance. In this eloquent tour de force, he takes Hemingway’s books and stories, one by one, and concisely analyzes and rates each of them.

While Sigal is busy cataloguing Hemingway’s body of work, he adroitly disposes of the silly yet persistent myth that this man was some sort of misogynistic, anti-feminist ogre. Read this account of Hemingway’s complex rendering of various female fiction characters. Read it carefully. When you finish, you’re going to wonder how on earth Papa ever got that rap of being “anti-women.”

David Macaray, an LA playwright and author (“It’s Never Been Easy: Essays on Modern Labor”), was a former union rep.

Spread the word