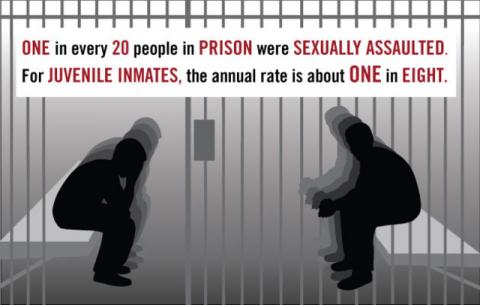

When Congress passed the Prison Rape Elimination Act in 2003, it didn't really know what it was passing. That was kind of the point, actually. Prison rape should be avoided -- that much was clear -- but there wasn't a comprehensive understanding of how pervasive the problem was or which prisoners it affected. So PREA created a commission to study "the impact of prison sexual assaults on federal, state and local government functions and on the communities and social institutions in which they operate." That commission released its findings in 2009, and waited for the U.S. Attorney General to make a determination about how those findings should be set into law. By that point, the National Institute of Justice, Human Rights Watch, and the Bureau of Justice Statistics had already made some startling conclusions -- namely that about five percent of surveyed prisoners admitted they had been raped, which amounted to more than 60,000 cases of prison rape per year.

Last year, PREA standards were finally set. This week, more than a decade after congress passed PREA in July 2003, those standards went into effect. Most of the converage of how these standards will influence prisons comes from local newspapers. A good summary comes from the Times Daily, a Florence, Ala.-based paper that covers counties just South of the Tennessee border. The coverage focuses significantly on how the standards will affect younger prisoners, and what the new standards will cost. From Mary Sell, a Times Daily reporter based in Alabama's capital:

Congress passed the Prison Rape Elimination Act in 2003, a policy against sexual abuse in federal, state and local facilities. The act’s standards are just now going into effect. Among them: No inmate under 18 may be placed in a housing unit where contact will occur with adult inmates in a common space, shower area or sleeping quarters.

Outside of housing units, agencies must either maintain “sight and sound separation” between youth and adult inmates or provide direct staff supervision when the two are together. Agencies must make their best efforts to avoid placing youthful inmates in isolation to comply with the act. “We have until August of next year to have 10 of our correctional facilities audited,” Thomas said. “We are not meeting that standard now, but we are working on it.”

He said one solution may be to house all teen inmates in one facility, away from older inmates, where they can have educational and vocational opportunities. Another possibility is contracting with an outside agency to handle teens who have been sentenced as adults. “We are looking at some other options now, but we’re not far enough along to discuss them,” he said.

States that don’t meet the new requirements could lose 5 percent of their Justice Department money, unless their governors certify that the same amount of money is being used to bring the states into compliance. That’s not a big financial incentive, though. Of the Department of Corrections’ $437 million in 2012 funding, about $9 million came from federal stimulus and bonus funds. About $941,000 came from federal grants.

The department is the state’s second biggest non-education expense. According to the its July monthly report, the latest available, Alabama prisons were at 189 percent capacity while being staffed at about 60 percent. “When it comes to prisons, it is the same story, different day: How do you pay for it?” Ward said.

He said advocates against putting teens in prisons have some valid points, but it’s a complex issue and convincing the general public that some of these offenders don’t belong in prison would be a tough sell.

“Youthful offenders can remain in DOC custody, but in order to comply with (the federal act), you will have to segregate them from the general population,” he said.

Thomas said he doesn’t necessarily disagree with those who say teens should be housed separately.

“They don’t need to persuade me their arguments are valid,” he said. “To me, we should be focusing on a solution, not whether they are right or wrong.”

A report this month from the advocacy group Campaign for Youth Justice shows that during the past eight years, 23 states have passed legislation to reduce the prosecution of youths in adult criminal courts and end their placement in adult facilities.

This will be an interesting story to follow. There have already been reports about how the new standards will affect LGBT prisoners and jail budgets. Stay tuned for more.

Reprinted with permission from In These Times. All rights reserved.

Portside is proud to feature content from In These Times, a publication dedicated to covering progressive politics, labor and activism. To get more news and provocative analysis from In These Times, sign up for a free weekly e-newsletter or subscribe to the magazine at a special low rate.

Spread the word