As Cecily McMillan was led to a cell in handcuffs amid uproar from her supporters, the 12 jurors who had just convicted the Occupy Wall Street activist of assaulting a New York police officer were whisked away in a police van. On the two-mile trip north through Manhattan to Union Square, where they were deposited well away from Monday's courtroom commotion, some pulled out mobile phones and began searching online for news on the trial they had just spent a month of their lives considering.

Finally freed from a ban on researching the case, including potential punishments, some were shocked to learn that they had just consigned the 25-year-old to a sentence of up to seven years in prison, one told the Guardian. "They felt bad," said the juror, who did not wish to be named. "Most just wanted her to do probation, maybe some community service. But now what I'm hearing is seven years in jail? That's ludicrous. Even a year in jail is ridiculous."

Though it came as a surprise to some of the eight women and four men who found her guilty of second-degree assault, McMillan said that the potential prison sentence had been on her mind for the two years since she was arrested for elbowing Officer Grantley Bovell in the face at a demonstration in Zuccotti Park, where protesters had gathered to mark six months of the Occupy movement.

"It has taken over my personhood," McMillan, a graduate student at the New School, told the Guardian in an interview last week. "I haven't been able to be excited about reading, or writing, about being Cecily. Can you imagine dating? That's like a great first statement: `Hey, well you know, this is great, and I really like you - but I might go to prison for seven years.'"

As she considered her fate between bites of pizza in her attorney's shabby offices near the Manhattan criminal courthouse, a brassy exterior that McMillan displayed throughout the trial began to slip. "I'm terrified. I'm absolutely terrified, of course," she said. Disclosing that her 23-year-old brother, James, was currently serving a sentence for drugs offences in a Texas jail, she said that she understood the harsh reality of life inside.

On the other hand, she went on, being locked away would at least end all the uncertainty. "Even in a six-by-six cell, just to have some fucking peace and quiet, so I could just sit with my thoughts for a minute, or even cry, or even get upset," she said, trailing off as her voice cracked, before coughing and promptly pulling herself together.

It was the last day of testimony at the end of a four-week trial, but McMillan was trying to stay in an upstanding mode. Bolstered by her immaculate daily appearance in smart dresses, pearls and high heels, it seemed intended as the opposite of how a judge and jury would expect a violent protester to look and act. One morning early on, she startled a police officer guarding the courtroom by thanking him for his work. "Everyone says you have been so nice," she told him. Without fail, she stood to attention and smiled politely at the jurors as they entered and exited several times each day. A chic handbag sometimes rested on the table beside her.

Police arrest protestor on the Brooklyn Bridge as part of an Occupy Wall Street protest.

Photograph: Julie Dermansky/Corbis // The Guardian

In the end, it made no difference. A grainy 52-second YouTube video of her clash with Bovell on the night of 17 March was enough to convince the jury beyond a reasonable doubt of the prosecution's case that McMillan deliberately struck the officer in the face as he led her out of the park, which was being cleared for cleaning - contrary to her defense that she had lashed out instinctively, not knowing Bovell was a police officer, after being grabbed on one of her breasts. Bovell suffered a black eye and said he went on to feel headaches and sensitivity to light.

McMillan's attorney, Martin Stolar, argued in court that the video clip was not clear enough to prove anything. Afterwards, he blamed it for the conviction. "I think that is the only piece of evidence that a jury could hang its hat on," he said. "On a quick glance without analysis, it looks like an assault. But it does not show what happened to Cecily."

The juror confirmed Stolar's fears. "For most of the jury, the video said it all," the juror said. The juror said that an immediate vote after the 12 were sent out for deliberation found they were split 9-3 in favor of convicting. After everyone watched the clip again in the jury room, the juror said, two of the three hold-outs switched to the majority, leaving only the juror who approached the Guardian in favor of acquitting the 25-year-old. Sensing "a losing battle", the juror agreed to join them in a unanimous verdict. "I'm very remorseful about it," the juror said a few hours later, having learned of McMillan's potential punishment.

Neither was the panel persuaded by McMillan's account of suffering bruising to her chest from being grabbed and enduring a seizure after being forcefully arrested by Bovell and his colleagues. Ultimately, the 12 - including a former nurse who said during selection that she treated victims of police brutality during the Columbia University riots of 1968 - were unmoved by photographs of bruises and by testimony that McMillan was seen convulsing on the pavement. Medical notes from two hospital visits on the night of the incident were seen to support the state's allegation that McMillan had invented her injuries, the juror said.

Also important for some on the panel, the juror said, was an abrupt allegation during closing arguments by Erin Choi, the assistant district attorney who led the state's prosecution, that McMillan had claimed to be unable to breathe during another brush with the police in December last year. "That's her MO," one the jurors apparently told others. Supporters of McMillan, whose lawyers say that she suffered post-traumatic stress disorder from the incident, are particularly outraged about the rejection of her allegation of being assaulted by the police.

Despite her team's insistence as a crucial plank of their defense that McMillan had been on a "day off" from Occupy and became caught up in the chaos at Zuccotti only while stopping to pick up a friend for a St Patrick's Day pub crawl that had already seen her consume several beers, they and her supporters condemned the court's verdict as evidence of a chilling crackdown on dissent and protest in New York.

McMillan claimed that this had been the state's motive behind her entire prosecution. "Being up there, seeing all those videos, hearing everybody talk like it's not you, or about you or even inclusive of you at all as a human being, it's like somebody holding your eyes open and making you watch `This is what happens to you if you're a protester,'" she said.

Her supporters accused Judge Ronald Zweibel of repeatedly siding with prosecutors and showing hostility to the defense team and their supporters. Zweibel barred Stolar from citing past claims of violent conduct by Bovell. When supporters entered court wearing paper hearts on their chests in an attempted show of solidarity, the judge furiously sent out the jury and ordered a police officer to confiscate the hearts. When a handful chuckled from the gallery at McMillan's bashful recounting of her university days in Wisconsin, Zweibel ordered them to shut up.

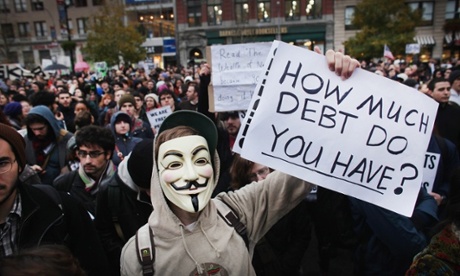

A large gathering of protesters affiliated with the Occupy Wall Street Movement attend a rally in Union Square on November 17, 2011.

Photograph: Spencer Platt/Getty // The Guardian

They also sharply criticized Zweibel for his prickly response to media coverage of the trial. After expressing vague anger during a courtroom sidebar about a Guardian report last month that his court was struggling to find jurors who were not biased against to Occupy, Zweibel went on to impose a total gag order on Stolar and Rebecca Heinegg, McMillan's second attorney, because of a seemingly innocuous remark Stolar made to the New York Times. McMillan's supporters described this as a violation of their first amendment rights.

But Choi cited that same constitutional provision in dismissing as "offensive" this argument, along with McMillan's account of the night and her insistence that she was innocent. "Our founding fathers did not create a right to free assembly so people could commit crimes and hide behind their right to protest," Choi said, in her closing argument. "This has nothing to do with Occupy Wall Street," she said. "This case is only about this defendant assaulting a police officer".

Days before she would be remanded in the women's facility at Riker's Island, however, McMillan said that any prison sentence she received would have everything to do with Occupy Wall Street, and the commitment to activism that it had inspired. "I easily have a year or two years' worth of material that I would like to read," she said of how she might spend the incarcerated life.

She is "obsessed" with Bayard Rustin, a leader of the early civil rights movement from the late 1940s, she said, and is basing her graduate thesis on his work. "I would chart from the 1880s in the United States all the way through Occupy, and I would have a blast with that," she said. "I'm so excited about that."

McMillan is due to be sentenced on 19 May. She rejected an earlier offer from prosecutors for her to plead guilty, which still would have resulted in her being classed as a felon, in exchange for a recommendation to the judge that she should not receive a prison sentence.

Afterwards, she said, she wants nothing more to do with New York and plans to move back to Atlanta, Georgia, where she spent much of her childhood, to work as a community organizer. And she said she expected to emerge unbowed from her punishment.

"People can take all sorts of things away from you besides dignity," she said. "And this is something I can sleep with. That doesn't mean I'm an idiot: it's going to be hard, and I'm sure I'm going to totally break down and spend six weeks in a trauma-stress, freaking out. But I know what I look like, and I know who I am."

[Jon Swaine is a US correspondent based in New York. He previously covered the US for the Daily Telegraph.]

Spread the word