I spent several days in New York last week with students from around the country who were preparing to head into the heartland to help organize Walmart workers for better jobs and wages. (Full familial disclosure: My son Adam is one of the leaders.)

Almost exactly fifty years ago a similar group headed to Mississippi to register African-Americans to vote, in what came to be known as Freedom Summer.

Call this Freedom Summer II.

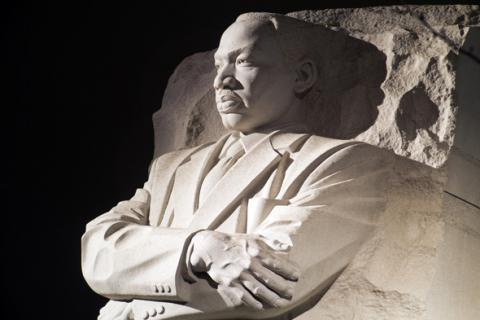

The current struggle of low-wage workers across America echoes the civil rights struggle of the 1960s.

Today, as then, a group of Americans is denied the dignity of decent wages and working conditions. Today, just as then, powerful forces are threatening and intimidating vulnerable people for exercising their legal rights. Today, just like fifty years ago, people who have been treated as voiceless and disposable are standing up and demanding change.

Although Walmart is no Bull Connor, it’s the poster child for keeping low-wage workers down. America’s largest employer, with 1.4 million workers, refuses to provide most of them with an income they can live on. The vast majority earns under $25,000 a year, with an average hourly wage of about $8.80.

You and I and other taxpayers shell out for these workers’ Medicaid and food stamps because they and their families can’t stay afloat on what Walmart pays. (I’ve often thought Walmart and other big employers should have to pay a tax equal to the public assistance their workers receive because the companies don’t pay them enough to stay out of poverty.)

Walmart won’t even allow workers to organize for better jobs and wages. In January, the National Labor Relations Board issued a complaint accusing it of unlawfully threatening or retaliating against workers who have taken part in strikes and protests.

The firm says it can’t afford to give its workers a raise or better hours and working conditions. Baloney. Walmart is America’s biggest retailer. Its policies are pulling every other major retailer into the same race to the bottom. If Walmart halted the race, the race would stop.

Don’t worry about its investors. Its largest is the Walton family, whose combined wealth is greater than the combined wealth of the bottom 42 percent of the entire American population.

This week, Walmart employees will go on strike in dozens of cities. A group of “Walmart Moms” is also marching for better hours and better treatment of pregnant women employees. And an employee group has sent a letter and voting guide to shareholders asking that they vote against Rob Walton’s re-election as chair.

Walmart isn’t the only place where low-wage workers are on the move. Two weeks ago, 2,000 protesters gathered at McDonald’s corporate headquarters in suburban Chicago to demand a hike in the minimum wage and the right to form a union without retaliation. More than 100 were arrested.

Giant fast-food companies have the largest gap between the pay of CEOs and workers of any industry, with a CEO-to-worker compensation ratio of more than 1,000-to-one.

Meanwhile, across America, low-wage workers are demanding – and in many cases getting – increases in the minimum wage. Despite Washington’s gridlock, seven states have raised their own minimums so far this year. A number of cities have also voted in minimum-wage increases.

The movement of low-wage workers for decent pay and working conditions is partly a reflection of America’s emerging low-wage economy. While low-wage industries such as retail and restaurant accounted for 22 percent of the jobs lost in the Great Recession, they’ve generated 44 percent of the jobs added since then, according to a recent report from the National Employment Law Project.

But the movement is also a moral struggle for decency and respect, and full participation in our economy and society. In these ways, it’s the civil rights struggle of our time.

It took guts to take on the power structure of Mississippi a half-century ago. It takes guts to take on the power structure of giant companies like Walmart and McDonalds now.

But confronting such powerful bastions is a vital step toward fundamental social change. Freedom Summer II is just the start.

Spread the word