Ed Miliband, the leader of the British Labour Party, has urged everyone in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland to fly the Scottish flag outside of their homes on Thursday, the day of the Scottish independence referendum.

Designed as a ploy to convince undecided voters of the strength of feeling for the union, this is the political equivalent of a plastic bouquet of gas station flowers, bought to rekindle the embers of a loveless marriage after every other store has closed. Based on a surge in support for independence in recent polls, it is possible that the flags that will go up in London on Thursday will resemble the decorative trimmings of a funeral procession.

I spent the last month doing some work in Glasgow, where the Yes presence was ubiquitous. On the backs of cars, on billboards, and on stickers peeling from lamp posts and windows. It was a message that seemed to transcend the regional and class divides that usually provide road maps for voting intentions. I saw Yes posters adorning the double glazed windows of grand Edinburgh townhouses, and hanging from the thirtieth or fortieth floors of crumbling public housing projects on the East End of Glasgow. The only anti-independence posters I have ever seen have been in England.

Opposite my home in London, a house is currently flying a giant Union Jack with a tiny Scottish saltire emblazoned on its center. It looks shockingly out of place, like the flag of a ghastly neofascist future state. In Scotland, I asked an independence-supporting friend about this discrepancy of posters, and what it meant for the result of the referendum. He was pessimistic, claiming that every house without a Yes sign, and every car without a Yes bumper sticker, would be voting “no.”

In the middle of August, when this conversation took place, his point ringed true. Until two weeks before the referendum, the No campaign was basking in the glow of inevitable victory. For years the polls had shown something like a 20-point lead for the awkwardly named “Better Together” campaign. Mainstream political news in Britain was dominated by fractious debates about the European Union (EU) and by predictions about next year’s general election, with only occasional mentions of a referendum that could alter the British political calculus forever.

Last week, however, a respectable poll unexpectedly showed a narrow lead for the Yes campaign, and all hell broke loose. Now the trains and planes that shuttle between London and Edinburgh are packed standing with MPs and Ministers racing to preserve a 307-year-old political union that until last week had been taken for granted. Amid dark rumors of a “missing million” of unaccounted-for voters, and of a possible last-minute endorsement by a powerful Murdoch-backed newspaper, panic is beginning to set in.

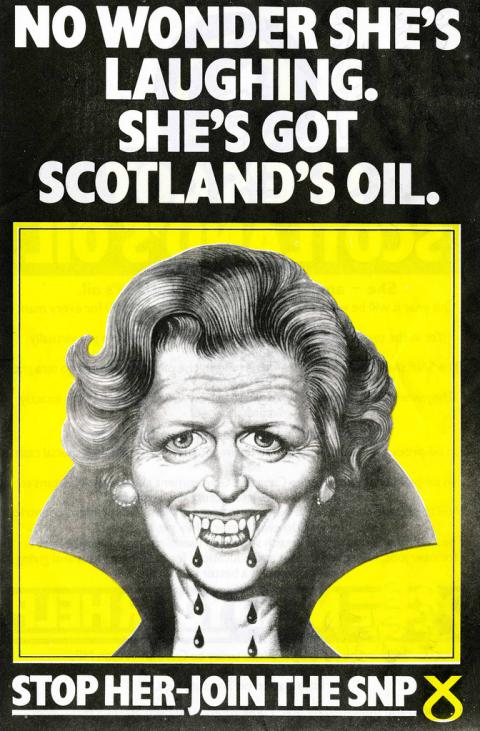

The rise of modern Scottish nationalism is, in many ways, inseparable from the discovery of large reserves of oil in the North Sea in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Although the Scottish National Party (SNP) had existed since the 1920s, for the first fifty years of its existence it was an extremely marginal force in British politics, usually only able to contest a small handful of parliamentary seats. The discovery of oil, however, provided a viable blueprint for a future political economy for Scotland. By the mid-1970s, the party won eleven Westminster seats and 30% of the vote in Scotland, all under the slogan “It’s Scotland’s Oil.”

Currently the billions of dollars of revenue generated from taxing oil companies operating on the North Sea fields goes to London. The SNP have claimed that this money is enough to build and maintain an independent Scottish state. Oil is currently essential to the politics of the Yes campaign, and if independence goes ahead, Scotland stands to inherit 91% of this tax revenue. Alex Salmond, the leader of the SNP and the likely future prime minister of an independent Scotland, is a former leading oil economist, who worked for a major Scottish bank. Scotland, then, could be the world’s newest petro-state.

The political theorist Timothy Mitchell has argued that the kind of protectionist, developmental states that proliferated during the middle of the twentieth century were solely enabled by large reserves of oil. Previously, he argues, the development of national economies as single, calculable units, had been arrested by limitations over energy. In the eighteenth century, for example, the burning of wood was unable to release enough energy to sustain an industrial revolution, while, in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the extraction of coal was too prone to sabotage by restive labor unions.

Before anxieties about the limitations of oil reserves and the devastating environmental effects of fossil fuels arrived in the 1970s to spoil the party, the anticipation of limitless oil reserves allowed many states to assemble the kinds of corporatist, protectionist welfare-state economies that, in the past thirty years, have been chipped away at by neoliberalism and globalization. By anticipating the creation of limitless prosperity thanks to a predictable stream of oil, an independent Scotland would attempt to make the kinds of long-term economic calculations that nation-states were once made of.

In many ways, then, Scottish nationalists are attempting to revive a much older political form. The state, as a technology to solve welfare and social problems, belongs to a mid-twentieth century political moment that has arguably passed. Many on the Left in Scotland, furious at savage public sector cuts imposed by a Conservative government that few in the country voted for, have formed an unlikely alliance with the once-right-wing SNP in the desperate hope that the process of state-making, lubricated by North Sea oil, will preserve a diminishing public sector.

For the Left, this may turn out to have been a Faustian pact. While the SNP has a record of supporting public sector spending, Alex Salmond has boasted of making Scotland’s corporation tax lower than Britain’s, and it’s certainly possible that post-independence Scotland and the United Kingdom will be forced into a bitter competition to create the best business environment, at the expense of Scottish and English working conditions.

In other ways there is something radically modern about the Scottish independence movement. I have written in Jacobin about the emergence in the last thirty years of a new relationship between politics and national space. Since the late 1970s, the once unified political economies of many nation-states have fractured. The emergence of “enterprise zones,” “special economic zones,” neoliberal “charter cities,” and other exceptional, and at times utopian, free-market spaces have pierced holes in the once-unified fabric of many political economies, creating rival and dispersed economic sovereignties.

Meanwhile, from the spread of nuclear-free zones in the 1980s to attempts to perfect a variety of new kinds of political formations during the Occupy movement, the Left has also used space for demonstrative political purposes with increasing frequency.

As global sovereignty is being dispersed and reconstituted, shattered into competing local zones on the one hand, and stretched taut between amorphous supranational bodies such as the EU on the other, the politics of nationalism feel curiously out of place. In this climate the Scottish independence movement feels almost like a postmodern pastiche of a previous political order.

It is difficult to say how an independent Scotland would fit into this new geography. Would it be like an enterprise zone, slashing taxes to compete with its southern neighbor for capital? Or would it exist as an attempt to preserve in aspic more social-democratic practices and policies, and to show the world that a viable welfare state can be assembled out of oil revenue? An independent Scotland could be either of these things, but it couldn’t be both.

In the many heated discussions I have had about this issue over the previous few days, I have tried to argue against independence in a way that avoids the trappings of sounding either like a reactionary troll, a naïve Labour Party ideologue, or a smug “there is no alternative”-style neoliberal. I have tried to articulate a position that opposes independence for the leftist reasons for which it should be opposed, without sounding pessimistic about, or shutting down the possibility of a more open-ended and progressive future. It has not been easy.

Left-wing supporters of independence argue that a “yes” vote would be a blow to an ossified, corrupt, out-of-touch London elite. This is an argument I have trouble buying. Rupert Murdoch is rumored to favor independence (although it’s likely his final decision will await a few more days of polling), an ominous pronouncement for those concerned about the relationship between the future Scottish government and powerful elites. What’s more, it is unlikely that an independent Scotland will be able to resist the influence of oil-related companies such as Ineos, the sole owners of the enormous Grangemouth Oil Refinery on the Firth of Forth.

In the nineteenth century, the early liberal reformer William Cobbett raged against something he called “The Thing.” The Thing referred to an amorphous and ill-defined political corruption that he took to be invisible, yet ubiquitous. It was a formal and capacious category, a superficial critique of the visible surface of politics, lacking the historical and structural depth which later radicals would expose.

In Scotland, The Thing is back. The Yes campaign’s rhetoric is largely focused on an ill-defined and anti-political critique of shadowy forces in Westminster, with little awareness of the neoliberal policies and ideas that motivate such forces. Without this consciousness an independent Scotland risks becoming a smaller, and potentially more reactionary, version of its neighbors to the south.

There is a still-uglier side to Scottish independence, however. On Wednesday, an independence supporter in Glasgow donned a rickshaw wired with a loudspeaker and chased a group of backbench Labour MPs through the streets, playing the Imperial March theme from Star Wars. On Youtube, he called the video “The Empire Strikes Back.” The implication is that Scotland, like Kenya or India, is just another colony, at last seeking its rightful independence.

I remember visiting the recently renovated National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh and being struck by the absence of any critique of Scotland’s participation in the British imperial project. Smiling Scots were pictured in North America, in Africa, and in India, where they worked enthusiastically as missionaries and colonial governors. In 1938, Glasgow played host to a national Empire Exhibition, an enormous display of imperial pomp visited by 12 million, which restructured the city for decades.

The likening of Scottish independence to anti-imperial movements is a devastating repression of Scotland’s own deep complicity in the British imperial project. Such a comparison was made last week by the journalist Robert Fisk, who likened the situation in Scotland to that of early twentieth century Ireland. Such imperial amnesia is one of the risks of trying to achieve left-wing ends with nationalist means.

For all of these reasons, I remain to be convinced that the payoff for supporting the creation of a nationalist petro-state is worth the taint of involving ourselves in that kind of politics. If the Left is being asked to consider something as idealistic, exciting, and destabilizing as an independent Scotland, then why temper this excitement with a potentially ugly, nationalist taint, funded by oil and marketed by tax breaks for the rich?

Let’s preserve our idealism for a better political form. In the weeks after the referendum, we can start thinking about what that form might look like.

Spread the word