This article appears in the September 2024 issue of The Nation, with the headline “A Weimar Anti-Fascist in Palestine.”

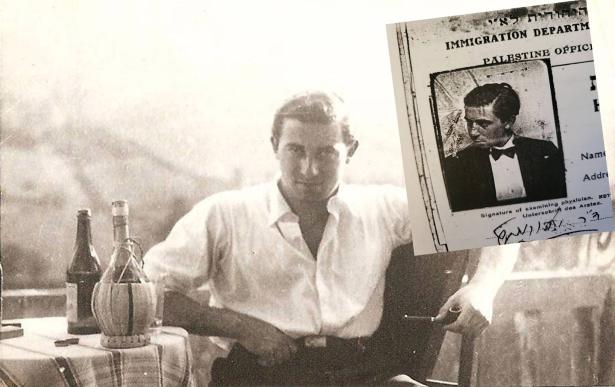

On April 1, 1933, the day of the Nazi boycott of Jewish businesses, my father, Wolfgang Yourgrau, then 24 years old, was attacked by a group of storm troopers in a Berlin shop. He fought back furiously (he was a university boxer) but was badly beaten. Through almost grotesque luck, he managed to recover from his injuries and avoid arrest—hiding out at a gynecological sanatorium for Nazi ladies run by an old girlfriend. After more furtive weeks in Berlin, my father, an assimilated Jew and a vocal anti-fascist who would later become an internationally known physicist and philosopher, left Germany and the collapsed Weimar Republic on a forged passport. From 1934 to 1948, he found refuge in Palestine under the British Mandate—not as a Zionist but as a political exile.

The story of his bloody Nazi brawl and high-adventure escape was part of the familial lore as I was growing up in 1960s Denver, where my father taught at the university. It headlined the miscellany of juicy tidbits from his Berlin life that he’d recite in our Rocky Mountain living room, his mood mellowed by a glass of pink gin, and which I’d welcome hazily as highlights from his heroic age of yore, along with tales of his student times under Albert Einstein and Erwin Schrödinger.

For her part, my mother, Thella, a Jew from South Africa who had migrated to Palestine in the 1930s, not under duress, was fond of retelling how in 1946 she was working as a secretary at the British Army offices in Jerusalem’s King David Hotel when the building and its occupants were dynamited by Zionist terrorists. Forty-one Arabs and 17 Jews were among the 91 killed. By sheer luck, my mother was off that day, at the beach.

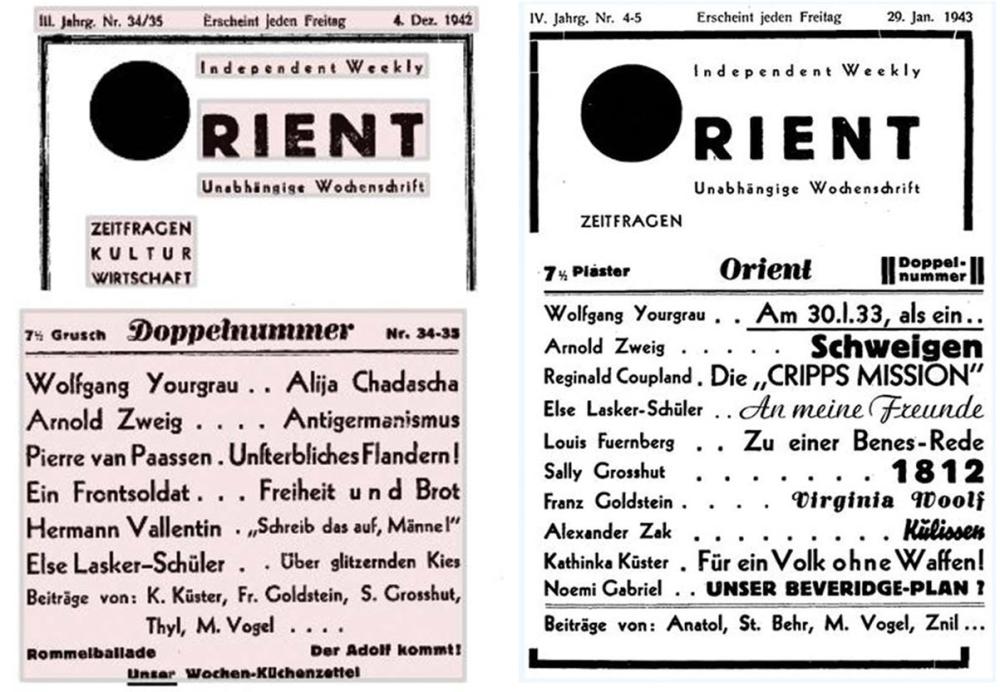

My father had his own unnerving brush with Zionist terror in pre-Israel Palestine, though he never brought it up. During his time there, he published a controversial German-language political and cultural weekly called Orient, which, though quixotic and short-lived, is recognized as part of the German exile press—newspapers and magazines of German-speaking exiles who had fled Hitler, including the likes of Thomas Mann and Bertolt Brecht. A distinctive outpost of this press in Palestine, Orient offers a fascinating window into the forces already stirring there, as well as the travails of some of its German Jewish refugees. After almost a year of being the target of constant hostility from a wide spectrum of the yishuv (the community of Jews in Palestine before Israel’s 1948 founding), Orient was finally silenced when a bomb blew its print shop to pieces.

Unpopular opinions: Two of the 45 issues of the German-language journal Orient, published by Wolfgang Yourgrau.

I learned all this only long after my father died, while I was researching my memoir, Mess, a decade ago. Digging further in the appalling wake of October 7, I’ve come to the acute realization that the story of my father’s exile and his milieu is a cautionary tale, one that evokes a dark, internecine version of the currents swirling toward Israel’s birth, currents that have swept through the decades to today’s horrors in Gaza and the West Bank. And it undercuts any consoling narrative that nationalist Zionism’s embrace of—even devotion to—ruthless force became visible to Jews only recently, or that Palestine’s Jews were united behind the brand of Zionism that was bent on establishing a Jewish nation-state; on the contrary, there were dissenters from the earliest days, and they were not just scorned but too often viciously punished.

In this context, my father’s relentless insistence that fascism and toxic nationalism could arise anywhere, among Zionists too, is a starkly urgent lesson, an alarm that’s blaring right now, in Israel and, eerily, even in Germany, with its stifling of pro-Palestinian voices. “The totalitarian specter is…wreaking havoc in the Jewish camp,” my father wrote at the turn of 1943. “Grab it by the throat wherever you meet it,” he implored.

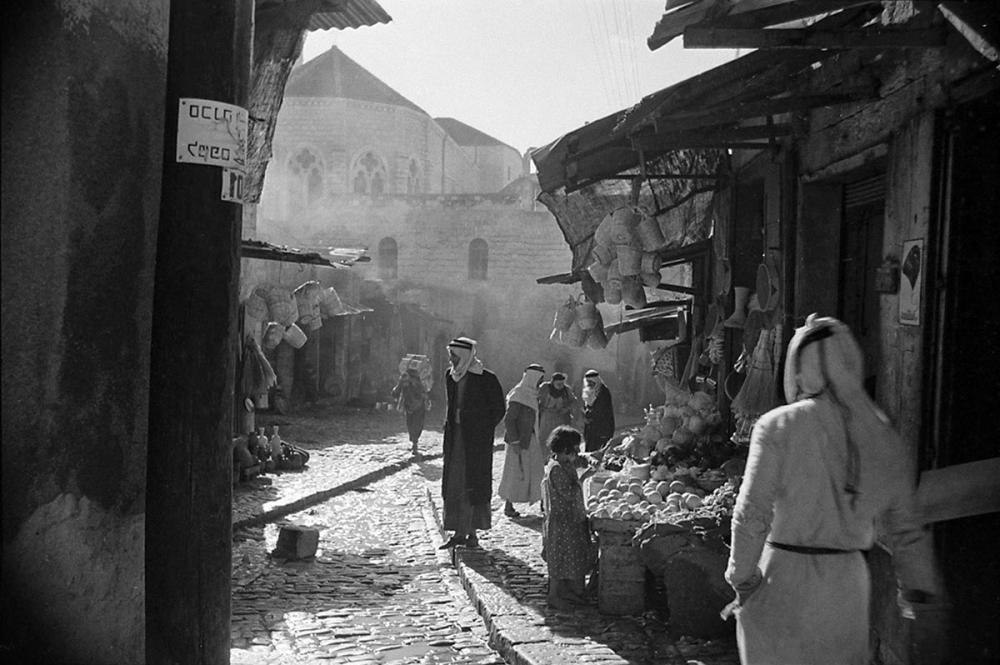

A day in the life of Palestine: Palestinian men sell their goods and survey each other’s wares on a street in Nazareth, circa 1935. (Staff/ Mirrorpix / Getty Images)

My father was born in 1908 and grew up in Berlin as the only child of a nonobservant Jewish mother and a father he always described as a Belgian Catholic. (He was, I discovered only recently, an Ashkenazi Jew from Grozny, Chechnya, who resided in Belgium from 1914 until his death, converting to Catholicism at some point.) My father’s parents divorced dramatically when he was a year old, and my grandfather departed the scene. My father spent long stretches in the company of three maternal uncles, all married to gentile women and all German nationalists, like many German Jews were at the time. As a boy, my father passionately followed suit. In gymnasium, or high school, a charismatic teacher ignited in him a never-extinguished devotion to bildung, the idea of morally ennobling culture and education, of which Germans held themselves supreme exemplars, with Goethe, Kant, Hegel, Heine, Bach, and so on. This devotion was particularly fervent for the German Jewish intelligentsia, which Amos Elon so eloquently records in his elegiac history The Pity of It All. Their “true home…was not ‘Germany’ but German culture and language,” Elon writes. When Vienna’s Theodor Herzl, the father of political Zionism, needed refreshing while writing (in German) his seminal text, The Jewish State, he listened to Wagner.

As Weimar’s efflorescence reached full bloom, my father immersed himself deep and wide. The University of Berlin occupied the center of the physics universe; he became a teaching assistant of the worldly Schrödinger and a student and somewhat friend of Einstein, with whom he sat in on cello several times in the string quartet in which Einstein played violin. He was involved in theatrical productions and corresponded with Herman Hesse. And he socialized often with the wealthy crowd of his gentile cousins.

At the same time, he led a double life. Deeply stirred by the other face of Weimar—the economic ravages, the looming shadow of Nazism—he was already a committed socialist and anti-fascist, an early member of Willy Brandt’s small left-wing party. He taught evening classes to workers, and to help cover his university fees, he found jobs on Berlin’s tough building construction crews. He took a leave from his doctoral studies to travel around giving speeches whose theme was “fascism means war.”

Then came the attack by the storm troopers and his flight from Germany—first to Latvia, then to Poland, where my father continued his anti-Nazi warnings, only to be taken for a communist and told to leave by the authorities. He declined trying for asylum in Belgium (where he would be drafted) or the Soviet Union (he wasn’t a communist) or the United States (he was doubtful of its anti-fascist commitment). Other options were limited by entry restrictions. Finally, with the aid of the prominent Zionist Robert Weltsch, my father, a young man of Weimar and Berlin, arrived in Palestine, wrenched from his homeland, in 1934.

At the time, Palestine was administered by Britain under a mandate from the League of Nations. That mandate, in line with the terms of the Balfour Declaration of 1917, required the establishment of “a national home for the Jewish people” (“national home” not precisely defined)—without harming the rights of the resident Arabs. It was a tumultuous moment. As Jews fled Nazism and antisemitism in Central Europe, pouring into a land that was more than 75 percent Arab, my father arrived in a world that was a welter of competing drives and nationalisms.

Zionism itself was riven by rival factions and visions, from the Labor Zionism of David Ben-Gurion, which represented the yishuv’s dominant ideology, to the Revisionist Zionism of Ze’ev Jabotinsky, an Odessa-born admirer of Mussolini, who in 1923 called for an “iron wall” of force as the only way to accomplish the Zionist project. Barred from Palestine by the British in 1930, Jabotinsky was a cofounder and head of such illegal paramilitary organizations as the Haganah, forerunner of the Israel Defense Forces, and the Irgun, the outfit responsible for the King David Hotel terror bombing and the 1948 Deir Yassin massacre. Another rogue player was the fanatical Stern Gang, which carried out terrorist acts against the British and Arabs, including at Deir Yassin. Other Zionist visions at the time included the religious Zionism of the Latvian-born Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, who argued for a messianic Jewish “return” to the Holy Land; his son would later galvanize members of the settler movement that has been ravaging the West Bank. And then there was the cultural Zionism of the Viennese philosopher Martin Buber and others, who envisioned a cultural/spiritual Jewish homeland in a binational state with Arabs.

As the Zionist presence swelled, Palestine’s indigenous Arabs nursed their own national aspirations, along with growing alarm at what they understood to be the intensifying colonial ambitions of the Jewish population, to say nothing of the enduring grip of British imperial rule. This culminated in the Great Arab Revolt of 1936 to ‘39—“a popular uprising, on a massive scale,” in the words of the historian Rashid Khalidi—which the British suppressed with overwhelming force, killing at least 5,000 Palestinian Arabs. All the while, the various Zionist paramilitaries ratcheted up their attacks on the British—and the Arabs and other Jews—with bouts of terrorism.

A history of violence: The bombed-out shell of the King David Hotel, which was targeted by the Irgun in June 1946. (HUM Images / Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Such was the world my father discovered when he arrived in Palestine, but with one additional, complicating twist particular to his condition as an immigrant from Germany. Before 1933, the yishuv’s numbers from Germany, where Zionism had a weak following, were a scant few thousand. By 1939, when immigration to Palestine was severely throttled by the British, some 60,000 German speakers had poured in during the so-called Fifth Aliyah (wave of immigration to Palestine), a great flood of some 250,000 Jews overall, most from Eastern Europe. Not zealots eager to construct a Zionist entity in the heat and dust, the Germans stood out as predominantly middle-class, well-educated refugees rushing for shelter. “They became displaced persons,” writes the scholar Yonatan Shiloh-Dayan, “in the sense that they neither belonged to their homelands nor to their new host society.”

The result was an ongoing multifaceted cultural tension. For one thing, as noted by Max Brod, Kafka’s Prague friend and a Zionist, “The real need was for young and vigorous people: pioneers, men of action, engineers, tractor drivers, chicken farmers, loggers and herdsmen.” The influx of German money was welcome. But intellectuals were not in demand.

My father’s entry documents listed his profession as “builder.” No mention of bildung.

Moreover, most of Palestine’s Zionists were Eastern European Jews, notoriously scorned as backward others by their arrogant German brethren. In Palestine, the shoe was painfully on the other foot. The new arrivals were derisively nicknamed Yekkes, most likely from the German word for “jacket,” a reference to their hopelessly out-of-place formal manner and dress. Fittingly, the photo on my father’s entry health certificate showed him in black tie.

And then there was the burning issue of language. The Zionists insisted on Hebrew as the language of the yishuv and resented and despised the use of German—likewise Yiddish, for that matter. The aim was for a new model of Jew: a bold and forceful Jew, a proud Jew proudly speaking and writing the ancestral tongue.

Sowing terror: A bus destroyed by a bomb that was set off by the Irgun, killing 11 Palestinians and two British constables. (Universal History Archive / Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

In an essay titled “my life in Germany before and after January 30, 1933,” which my father submitted to a competition sponsored by Harvard in 1940, he wrote (in German) from Tel Aviv that he was lecturing at the local Histadrut, the powerful Zionist labor union, “on questions around the Middle East” and contributing to an anti-fascist journal-in-exile in Europe. He was also finishing a book, “a scientific and critical” appraisal of Zionism.

The book on Zionism doesn’t seem to have materialized. In 1942, however, my father suddenly got the opportunity for a “critical appraisal” by acquiring the publishing permit of a German-language weekly called Orient, whose name he had to retain. My father became Orient’s publisher, editor, and editorial writer. Over its turbulent and erratic 38-issue life, it would always be produced by the seat of the pants—sometimes partly hectographed, not formally printed—its funding ever uncertain. Its pages, my father explained in the magazine’s first issue, were intended for those for whom learning Hebrew would remain an “unattainable goal” during the war. Orient would be a “tribune” for “factual contributions” regarding Palestine’s problems as well as international affairs and culture. While others in his exile milieu were just biding their time until returning to Europe, he was actively engaging with his situation.

The model for Orient was the Weimar era’s iconic anti-fascist leftist weekly Die Weltbühne (The World Stage) and its fearless martyred editor, Carl von Ossietzky. The Nazis arrested von Ossietzky—a prominent pacifist, as well as a gentile—the morning after the Reichstag fire in 1933 and shut down his publication. He received the 1935 Nobel Peace Prize while imprisoned in a concentration camp, thanks to an international campaign to give him the award as a way to help encourage his release. The honor was short-lived: Broken by torture, von Ossietzky died in 1938.

To fill the role of Orient’s figurehead co-editor and its marquee main contributor, my father enlisted Arnold Zweig, a Die Weltbühne veteran and a friend of von Ossietzky as well as Brecht and other notables. A German Jew, Zweig was a well-known Weimar literary figure and the author of the internationally acclaimed 1927 anti-war novel The Case of Sergeant Grischa. Some 20 years older than my father, he was a pacifist, socialist, and great advocate of psychoanalysis; he and Freud were warm correspondents. Unlike my father, Zweig was also a longtime cultural Zionist—though with diminishing ardor—who in 1920 had collaborated with the illustrator Hermann Struck on The Face of Eastern European Jewry, an effort to convey to German Jews the poignant humanity of their Lithuanian brethren, the scorned Ostjuden.

In 1933, Zweig watched from the crowd as his books were burned in Berlin’s Opera Square. He left Germany at once, reaching Palestine in 1933.

He arrived joylessly. Two years earlier, he’d published a novel inspired by the notorious 1924 assassination—by Zionists—of Jacob de Haan, a prominent gay, anti-Zionist, religious Jew: “Palestine’s first political murder,” Zweig called it. It had profoundly shaken him. “I view the necessity of living here among the Jews without enthusiasm,” he wrote to Freud from Haifa, “without any false hopes and even without the desire to scoff.” He would become increasingly miserable, alienated from Zionist nationalism and Jewish life in Palestine—and deeply resented and sidelined for using German and refusing to learn Hebrew.

The other prominent sometime Orient and former Die Weltbühne contributor was the Expressionist poet Else Lasker-Schüler. This fantastically bohemian German Jewish luminary of the Berlin scene was now elderly and living hand to mouth in virtual obscurity in Jerusalem, stranded in exile. My father was helping to support her. (He was at her bedside when she died in 1945.) A besotted Hebraic orientalist, Lasker-Schüler wrote in German and declined to have her poems translated into Hebrew.

“She dreamt Hebrew visions,” a writer noted in Commentary magazine, “but the only words she could clothe them in were German.”

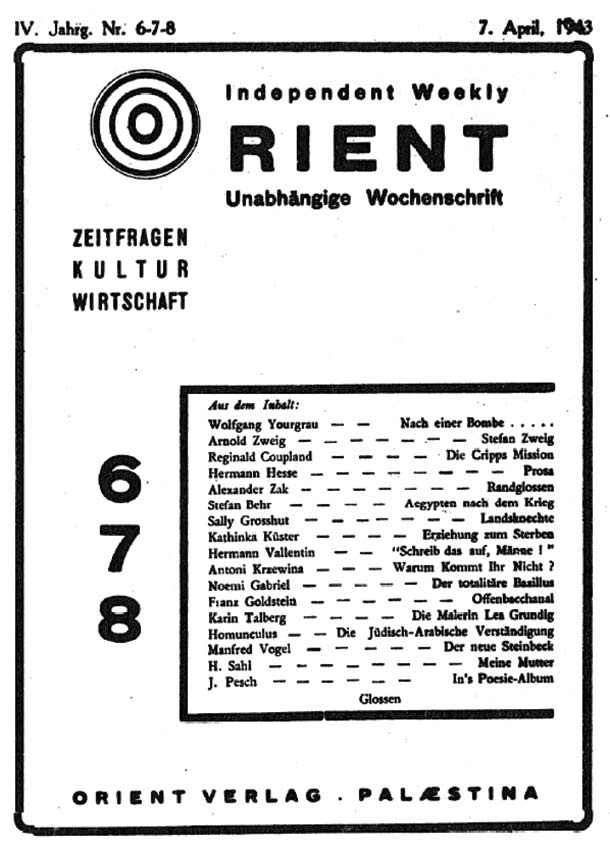

Last words: The final issue of Orient was published in April 1943, two months after a bomb destroyed their printers.

With such a provenance, Orient made its debut in April 1942.

“This Palestine is our fate,” my father declared in his opening editorial. “Few sought it, many fought it. But you cannot decree a homeland; you can only shape it with love and reason.” He was speaking for German Jews’ struggles to adapt and be accepted, but arguably too for the yishuv’s situation overall. With Die Weltbühne–style bite, he then deplored the way the “longing for Palestine” of “the European Jew” had become the narrow horizon of Zionist reality, a philistine “clod” of patriotism and provincialism, dominated by the “almost totalitarian” manner of its various actors. “We live in the Orient,” he insisted. “Arab peoples are our neighbors.” Rapprochement was a necessity if any form of Jewish homeland was to survive there.

He vowed that the magazine would be an independent voice, and he closed his editorial with a ringing credo: “We declare the fiercest fight against every fascist impulse, every attempt to restrict the right to freely form opinions, which is one of the eternal rights of humanity!”

Brave words.

A subsequent early issue notably swung its exile gaze back toward Europe, to the lost Jewish world of Viennese culture. The writer Stefan Zweig had recently died by suicide in Brazil. My father memorialized him as an aesthetic “aristocrat”—but faulted him, with unbending candor, for not being “a fighter…a champion of the idea of humanity, humanism, culture.” The issue also featured a eulogy by Arnold Zweig (no relation to Stefan) for his friend Joseph Roth, whose desperate warnings about Hitler had gone unheeded, and reprints of Stefan Zweig’s eulogy for Freud; Freud’s preface to the Hebrew edition of Totem and Taboo (in German); letters between Freud and Arnold Zweig; and two brief poems by Karl Kraus, the most caustic of moralists and anti-fascists and a ferocious guardian of the German language.

Upcoming issues would carry occasional acute assessments of the war’s developments—without neglecting critiques of the yishuv Zionists’ “almost totalitarian manner,” such as their violent dragooning of young Jews into joining the British Army to fight the Nazis (and gain experience for Zionist purposes in the process). My father excoriated the “excesses” of the Haganah and the fascist-styled youth movement Betar (another project of the Mussolini fan Jabotinsky).

From the start, and notwithstanding its small circulation, Orient drew heat from all quarters. “People started a boycott, wrote letters, and wildly agitated against us,” my father recalled in 1947. “They called us Communists, traitors to Zionism, and café literati. We were reproached for being a demoralizing influence, uprooted intellectuals, and typical Weltbühne people”—insults reminiscent of Nazi vocabulary, Jean-Michel Palmier noted in his monumental history, Weimar in Exile. Some socialists found the publication insufficiently radical, while its use of German infuriated, in my father’s words, the “language fanatics.”

And despite Orient’s frequent protests that Western European Jews were being unfairly sidelined in yishuv politics—“treated as a foreign, often unpleasant element”—many fellow German arrivals were also hostile. According to Hans-Albert Walter, an authority on the literature of exile, German Jews were accustomed to staying inconspicuous, keeping the peace. Orient was “too political and too principle-oriented, also too ‘loud’ and too ‘ostentatious.’”

On May 30, 1942, a speech by Arnold Zweig (in German, of course) at Tel Aviv’s elegant Bauhaus-style Esther Cinema was violently broken up by members of Betar. Zweig, 54 years old and with failing eyesight, a man whose books had been burned by the Nazis, was roughed up.

“Today, terror also seems to be the language of the Jews,” Orient declared in the aftermath. Terror by Jews against Jews.

In this hostile climate, with its journalists being assaulted, its printers and potential advertisers being warned off, Orient defiantly soldiered on. Zweig wrote a series, “Antigermanismus,” arguing against equating Nazism with Germany’s people and culture. My father polemicized in support of a binational entity shared by Jews and Arabs as the only viable and moral solution for Zionism—seconding the ultimately futile calls of Martin Buber and Judah Magnes, the American-born Zionist rabbi who founded Hebrew University. “Would that were large and empty enough to absorb millions of persecuted, wandering Jews and to be constituted into a Jewish state!” Magnes wrote in Foreign Affairs. “The fact remains that Palestine is small and it is not empty.” (A later admirer of Magnes’s “Other Zionism” was I.F. Stone, whose 1946 book Underground to Palestine is an account of a group of European Holocaust survivors who heroically attempted to reach the Holy Land by ship. He found himself ostracized in America, he wrote in 1978, for suggesting a binational state.)

“The Arab question is deliberately ignored and the national aspirations of the Arab people are either trivialized or obscured,” my father wrote in Orient in late 1942. With grim prescience, he added, “It remains the historic achievement of a small group of intellectuals to have clearly recognized the political danger zone that this negation of Arab national existence in Palestine created.” The bold attempt to “transform the national antagonism into a binational-state consciousness” was bound to fail, he concluded, because “it would have meant a modification of the Zionist concept.”

This concept had been starkly expressed that May at the Biltmore Conference in New York, when David Ben-Gurion called for a Jewish commonwealth for “historic” Palestine, on both sides of the Jordan.

By early 1943, my father was again vehemently warning that fascism was not exclusive to Germany and Italy. “The totalitarian specter is…wreaking havoc in the Jewish camp,” he wrote in what was to be Orient’s penultimate issue. “Grab it by the throat wherever you meet it…. Otherwise we in this country could be witnesses to the tragicomedy that is causing amusement among other peoples, that fascism would mature in Palestine at a time when the liberated nations would bury it.”

My father’s fears were almost immediately confirmed. On the night of February 2, 1943, a powerful bomb (or bombs) destroyed Orient’s printers in Haifa.

My father never said who he thought was responsible. A US intelligence report, cited in Thomas Suárez’s book State of Terror, ascribed the bombing only to “extremists.” “In short,” the report concluded, “Zionism in Palestine, apart from all its good aspects, has bred a type of nationalism which in any other country would be stigmatized as retrograde Nazism.” It was a nationalism that resorted to violence to get what it wanted, even against its own.

The last issue of Orient appeared, very haphazardly printed now in Jerusalem, dated April 7—precisely 10 years and one month after Die Weltbühne was silenced by the Nazis. Decrying the general “witches’ sabbath,” my father wrote: “People have accused my co-workers, myself and some of those who sympathize with this publication of being anti-Zionist…. To this there can be only one response: whoever…feels in the deepest reaches of their soul a surge of sympathy, responsibility and self-sacrifice for this Jewish community, must not remain silent about what has been happening here in this land for months, no, years. Has anyone still not noticed how we are gradually degenerating politically and therefore humanly to such a degree that even a few years ago we would have thought unimaginable?”

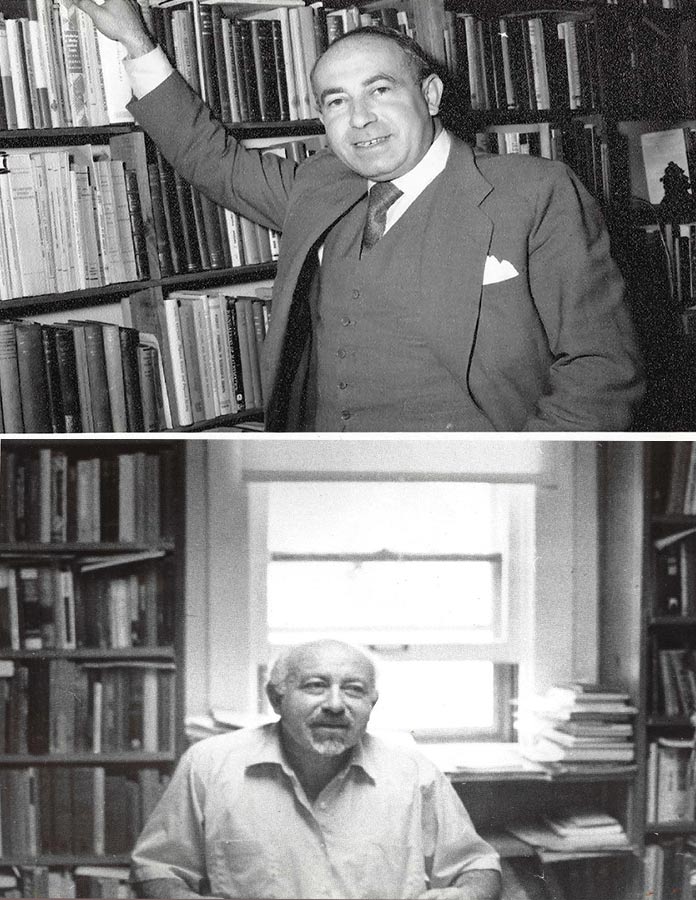

After exile: Wolfgang Yourgrau in his later years, which he dedicated to the study of philosophy and physics.

After the demise of Orient, my father was briefly the editor of German-language broadcasts for the Mandatory government’s Jerusalem Radio. In 1944, he was in Cairo working for America’s Office of Strategic Services, the short-lived precursor to the CIA, producing “black propaganda” to feed to the German army. Back in Jerusalem, he returned to academia at the British Council’s School of Higher Studies.

He and my mother met on VE Day in 1945 and married in 1947, second marriages for them both. In 1948, right before Israel became a state, they emigrated to South Africa—or rather, fled practically overnight from the chaos and gunfire, leaving behind my father’s vast library, papers, research, and international correspondence in storage at Hebrew University. These were never recovered.

My father’s life turned for good from politics to academia, a complete severance. After 11 years in South Africa, where my two brothers and I were born and where my father taught at various universities, we moved to the United States. In 1963, my father took a job at the University of Denver, where he remained until his death in 1979. (Strange to say, Benzion Netanyahu, the father of Bibi—and personal secretary to Jabotinsky when the latter was in America in 1940—also taught there during some of that time.) He cofounded an important international physics journal, Foundations of Physics (its current editor is the physicist and best-selling author Carlo Rovelli), and was close to Karl Popper, championing Popper’s philosophy of science. In the ’60s, he frequently visited East Germany to collaborate with fellow physicists. Perhaps he was reunited there with Arnold Zweig, who left Israel in late 1948 for what would become the German Democratic Republic, where he was celebrated and lionized. If they did meet, my father never mentioned it.

In 1970, a circle from his earlier world was closed: My father wrote one of the five official nomination letters successfully backing Willy Brandt for the 1971 Nobel Peace Prize. Brandt, when he was a young man in exile in Norway, had been fervently active in the Nobel Prize campaign for Die Weltbühne’s Carl von Ossietzky.

Which brings me to a complicating coda.

In 1975, the American Jewish Committee Holocaust Project recorded an interview with my father at his home. He had lost an uncle at Buchenwald and cousins elsewhere (so I would learn; he never talked about this either). Listening to the recording a few years ago, I noted his emphatic reiteration—his voice rising—that fascism could spring up anywhere under the right conditions. “God forbid America ever has 10 to 15 percent unemployment!” he said.

Revisiting that interview recently, I was bemused to register his brief but forthright comment that he’d changed his mind about Israel.

“I was against its establishment,” he declared. “But now that Israel has demonstrated its potential…its ability to survive surrounded by an Arab sea, I must take my hat off in admiration. I am convinced Israel is here to stay. It must never be allowed to disappear.”

As for Arnold Zweig, he got in trouble with the East German authorities for declining, as a celebrated cultural figure, to sign a petition condemning Israel during the 1967 Arab-Israeli War.

What to make of these expressions of support by Orient’s principals for “plucky Israel” (as the cliché goes) and its military muscle—muscle that had brought about Israel’s fateful, calamitous occupation of the West Bank and Gaza? Was it the case of old men distant from the sharp edges of their bygone struggles and insights? Zweig was almost 80 in 1967, in grievous health; he would die a year later. My father was 66 in 1975, suffering from depression and the heart disease that would kill him in 1979.

I don’t have any context to explain this development. My father never visited Israel, never expressed any desire to do so, never talked seriously about Israeli matters. But one possibility I have considered is that perhaps he and Zweig were affected by a deep and lingering gratitude to the place that had enabled them to survive. Despite all they had undergone among the yishuv—the pain of exile, the hostility and violence directed at Orient, the larger, outward-facing violence infecting the society—there, in Palestine, they avoided the fate of millions of Jews. In a late 1942 editorial, my father wrote these words:

We who linked our future to Palestine—in which case the distinction between Zionists and non-Zionists is insignificant—escaped destruction. While the Jews of Europe only have one certainty, namely their unstoppable downfall if the rage of the fascist beast is not stopped very soon, we, on our Jewish island, are trying to make our lives normal…. It’s probably no exaggeration when we are astonished to find that in probably no other country in the world have people been spared from the bitterness and horrors of war to the extent that we Jews in the towns and villages of Palestine have been.

Decades on, this paradoxical truth in my father’s story has lingered not just for those who survived the era but for scores of Jews born to later generations—forging an allegiance to an idea, and a state, that has inflicted far worse horrors than the ones my father witnessed during his time in Palestine. Now, as Israel commits daily atrocities in Gaza, I hope he would again have made the connection between the “rage of the fascist beast” in Europe and the carnage of Israel’s variant today. How could he not?

In that same 1942 editorial, my father wrote: “Officials use such laconic words to record human tragedies, of our friends and relatives who fell by the wayside, died in misery or chose suicide…. These thousands of unfortunate creatures will one day be spoken of when those responsible are sentenced.”

Here again, my father’s words proved painfully prescient. His friends and relatives, the millions of “unfortunate creatures” who died at the Nazis’ hands, were eventually spoken of when some of those responsible were sentenced. But it took far too long then—just as it is taking far too long now. The Palestinians slaughtered today, like the Jews slaughtered 80 years ago, cannot wait for the world to take action.

Barry Yourgrau is a fiction writer (Wearing Dad’s Head, The Sadness of Sex), memoirist (Mess), and journalist. His website is barryyourgrau.com.

Copyright c 2024 The Nation. Reprinted with permission. May not be reprinted without permission. Distributed by PARS International Corp.

Founded by abolitionists in 1865, The Nation has chronicled the breadth and depth of political and cultural life, from the debut of the telegraph to the rise of Twitter, serving as a critical, independent, and progressive voice in American journalism.

Please support progressive journalism. Get a digital subscription to The Nation for just $24.95!

Thank you for reading The Nation!

We hope you enjoyed the story you just read. It’s just one of many examples of incisive, deeply-reported journalism we publish—journalism that shifts the needle on important issues, uncovers malfeasance and corruption, and uplifts voices and perspectives that often go unheard in mainstream media. For nearly 160 years, The Nation has spoken truth to power and shone a light on issues that would otherwise be swept under the rug.

In a critical election year as well as a time of media austerity, independent journalism needs your continued support. The best way to do this is with a recurring donation. This month, we are asking readers like you who value truth and democracy to step up and support The Nation with a monthly contribution. We call these monthly donors Sustainers, a small but mighty group of supporters who ensure our team of writers, editors, and fact-checkers have the resources they need to report on breaking news, investigative feature stories that often take weeks or months to report, and much more.

There’s a lot to talk about in the coming months, from the presidential election and Supreme Court battles to the fight for bodily autonomy. We’ll cover all these issues and more, but this is only made possible with support from sustaining donors. Donate today—any amount you can spare each month is appreciated, even just the price of a cup of coffee.

The Nation does now bow to the interests of a corporate owner or advertisers—we answer only to readers like you who make our work possible. Set up a recurring donation today and ensure we can continue to hold the powerful accountable.

Thank you for your generosity.

Spread the word