DURING the second wave of pit closures in the 1990s, a 21-year-old LGBT activist was having an argument about politics and it’s one I have had on many occasions.

That argument, about whether or not gay people of his age were as political as those older than him, rages in the community to this day. When it was suggested that he support the mining communities, his initial response was: “Why on earth would I support them when they don’t support me?” To which his comrade replied: “Let me tell you a story...”

That man was Stephen Beresford and that story was of the 1984-85 miners’ strike and the support given to it by lesbians and gays. And it’s a narrative which writer Beresford and director Matthew Warchus got together to immortalise in the film Pride, which is in cinemas from Friday.

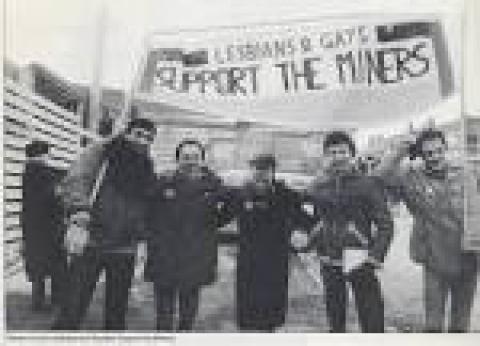

Turned away by unions, ignored by officials and shunned by their own community, it wasn’t until the Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM) group twinned with a small mining town in south Wales that anyone would take them seriously.

LGSM went on to raise over £20,000 for the miners and their families and hosted one of the most audacious fund-raising events in the history of the strike, the Pits and Perverts Ball.

Often when a film with LGBT themes is produced there can be difficulties of prejudice along the way and I was curious to know if the prodcuction team had encountered something similar.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the change in attitudes in recent decades, it wasn’t the LGBT but the socialist theme that people had an issue with.

A major US distributor went so far as to abandon the project entirely because it deals with socialism and from an early stage the crew were advised not to use the word “communist” under any circumstances or there’d be stiff opposition to marketing the film in the US.

This presented some difficulty not least because one of the main characters of the film and a founding member of LGSM is Mark Ashton, beautifully played by Ben Schnetzer. At the time he was the youngest-ever general secretary of the Young Communist League.

In tribute to his work, in an early scene of the film Ashton takes the stage of a London gay club and introduces himself. A voice can be heard in the crowd, which turns out to be Beresford’s, shouting: “Commie!”

Such moments — one of many in Pride — demonstrates the film’s potential not just in LGBT education but in the educational system generally.

Like many minority groups, our history is not one that is afforded much time in the average school curriculum. Many schools in Britain and abroad would still recoil at the idea of including LGBT history in their lesson plans.

Growing up, LGBT people need to seek out their history for themselves, something which advances in the internet has made much easier. Yet so often members of the younger generation don’t know where to start.

I was lucky enough to have an LGBT teacher who took me under her wing and gave me what she called my “queer education,” which included watching films like Beautiful Thing, Angels In America and Boys Don’t Cry.

The power of Pride is that not only will it now be included in this list, educating the next generation of LGBT people about their history and culture, it will also help instill a political context too.

The story of LGSM and the miners was one that lead to LGBT and equalities rights being at the forefront of trade union and labour movement policies. It was achieved by working together in solidarity with others who you may never have thought could share the same ideals as you.

That is the true meaning of this film — nstrength and unity against the oppressors.

My final question is I think a tough one, yet when I ask which scene they’d choose as their favourite there’s an immediate response from Beresford: “That’s easy. The one where Bill Nighy and Imelda Staunton spread margarine on bread together.”

I wholeheartedly agree.

To understand why you’ll just have to go and see the film for yourself. Hugely recommended.

Spread the word