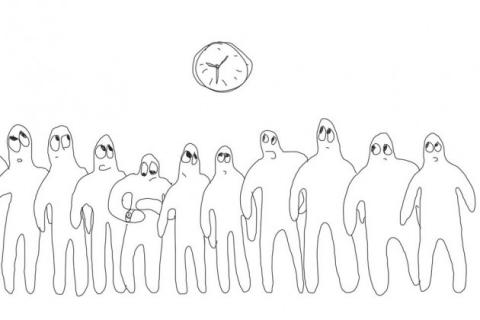

Amazon.com warehouses are full of stuff people like. To cut down on theft, workers who box and ship it are required to pass through security checkpoints after their shifts, waiting in lines that can take almost 30 minutes to get through.

On Oct. 8 the Supreme Court will hear arguments about whether that time counts as work. In 2010 two former employees of Integrity Staffing Solutions, a temp agency that supplies workers at many of Amazon’s U.S. warehouses, sued the company demanding back pay for the time they spent in security lines after clocking out at Amazon warehouses in Nevada. The security checks, the plaintiffs argued, were required by Integrity and therefore part of the job. (Amazon-employed workers go through the same checks.)

At issue is the scope of a 1947 amendment to the Fair Labor Standards Act that says employers don’t have to pay for time spent on work-related activities like getting to or from the office. Nine years later, the Supreme Court established in a pair of rulings that the key is whether the activity in question is “integral and indispensable” to the principal activities workers are paid to do. Butchers at a meatpacking plant, the court found, had to be paid for time spent sharpening their knives, and workers at a battery plant deserved compensation for time spent showering after work to wash off traces of sulfuric acid and lead.

The question in the Integrity case is whether security checks are more like those showers or more like commuting. With screenings increasingly common, the case could have implications for a wide range of workplaces. “There are literally billions and billions of dollars at stake,” says Paul Secunda, who directs the Labor & Employment Law program at Marquette University Law School.

Integrity says it doesn’t owe the workers money because the screenings weren’t directly related to their jobs. “No court has ever held that ‘not breaking the law’ is a principal job activity for which compensation must be paid,” the company’s lawyers wrote in a brief last May. Integrity, based in Wilmington, Del., has also done work for JPMorgan Chase, ING Direct, and Wal-Mart. Amazon wasn’t in the original complaint now before the Supreme Court. It has since been added to that suit, which has been consolidated with four similar lawsuits. In court filings it denied the claims. Neither Integrity nor Amazon responded to requests for comment.

Business groups have taken Integrity’s side. “The people here in the warehouse are not employed to go through a security screening,” says Edward Brill, who wrote a brief for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the National Association of Manufacturers, and others. The Departments of Justice and Labor also submitted on Integrity’s behalf. There is, Solicitor General Donald Verrilli Jr. wrote, “no clear-cut distinction—either in terms of purpose or effect—between petitioner’s screenings and those that are routine at countless government and private-sector buildings.”

The plaintiffs say there’s plenty that Integrity and other companies could do to make the lines move faster, like hiring more inspectors. That, they say, was one idea behind the Fair Labor Standards Act in the first place: If you make companies pay workers for their time, they’re less likely to waste it.

Spread the word