We first came across Dr. Oz back in 2009 when he was on Oprah peddling the weight loss benefits of infrared saunas.

As Travis pointed out, infrared saunas are not a miracle cure for obesity. Nor can they “liquefy fat cells.”

Over the years, Oz has enthusiastically promoted countless “miracles in a bottle” to his loyal viewership, offering new weight-loss potions on a weekly basis. At one time or another green tea extract, raspberry ketones, and garcinia cambogia were all touted as the next panacea for obesity. Meanwhile, those in the medical profession, researchers, and skeptics shook their head in disappointment.

When I was on a tour of the NBC building back in 2011, I was taken to the studio of his show, and was surprised to be the only one in my group of visitors who was NOT an Oz fan (I came for the SNL studio tour, obviously). I had asked the NBC guide about the legal ramifications of a TV doctor promoting health interventions based on folklore rather than scientific evidence. Before the guide had a chance to respond with rehearsed Oz propaganda, a couple of fellow visitors jumped at me with their eyes wild and mouths foaming, yelling out non-sequiturs about Big Pharma suppressing natural treatments, Oz being a saint, toxins in food, etc.

From this point forward, Oz’s cult-like following continued to grow, as did the ridiculousness of his claims.

Earlier this year, after some suave marketers used clips from the show to sell bogus products, Oz faced a grilling from a panel of U.S. senators about his weight loss product claims.

Claire McCaskill, chair of the consumer protection panel, asked Oz:

“I don’t get why you need to say this stuff when you know it’s not true. When you have this amazing megaphone, why do you cheapen your show?”

Oz responded with: “I’ve used flowery language…which was meant to be helpful, but wound up being incendiary and provided fodder for unscrupulous advertisers.” Then, with puppy dog eyes, he promised he’ll improve on what he promotes to his followers. He also shed a single tear.

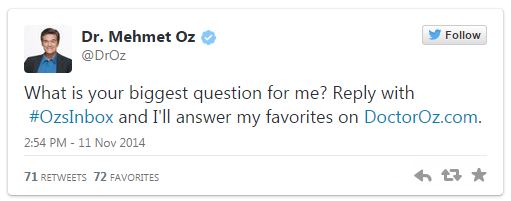

Next, on November 11, the following was tweeted from Oz’s Twitter account:

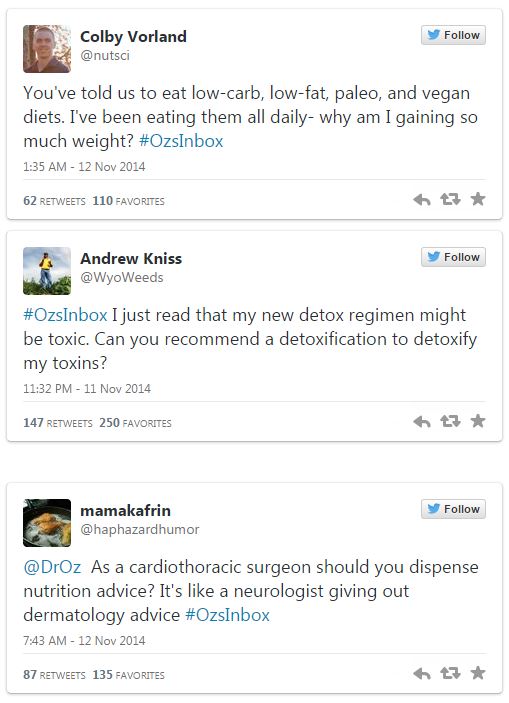

Unfortunately for Oz, this strategy backfired. Horrendously. Immediately after Oz (or more likely, his social media team) asked the question, Twitter gave Dr. Oz a hilarious slap across the face:

For more awesome examples, see Julia Belluz’s article.

Most recently, a study by a group of Canadian researchers from the University of Alberta, analyzed the health claims made on Oz’s show for strength of supportive medical evidence.

The study, published last week in the British Medical Journal and available online, revealed that only 46% of recommendations made by Dr. Oz on his show were supported by available scientific evidence. Conversely, available evidence directly contradicted his recommendations in 15% of cases, meanwhile no evidence was found to support 39% of recommendations.

And the show has no shortage of recommendations. According to the study, the show has an average of 12 recommendations per episode.

Oz’s favourite topic of discussion? Dietary advice makes up 39% of all recommendations on the show.

The authors’ conclusion is enlightening:

Consumers should be skeptical about any recommendations provided on television medical talk shows, as details are limited and only a third to one half of recommendations are based on believable or somewhat believable evidence.

What the future holds for Dr. Oz is anyone’s guess. At the very least, I hope a few of his loyal followers become skeptical of the BS being peddled as medical advice.

What are your thoughts? Should his medical license be revoked? Should his show be cancelled?

Peter

Reference: Korownyk et al. Televised medical talk shows—what they recommend and the evidence to support their recommendations: a prospective observational study. BMJ 2014;349:g7346

Peter Janiszewski has a PhD in clinical exercise physiology. He's a medical writer/editor, a published obesity researcher, university lecturer, and an avid traveler. You can connect with Peter on Twitter. For more information please visit his website.

Spread the word