Binyamin Netanyahu’s dramatic declaration to world leaders in 2012 that Iran was about a year away from making a nuclear bomb was contradicted by his own secret service, according to a top-secret Mossad document.

It is part of a cache of hundreds of dossiers, files and cables from the world’s major intelligence services – one of the biggest spy leaks in recent times.

Brandishing a cartoon of a bomb with a red line to illustrate his point, the Israeli prime minister warned the UN in New York that Iran would be able to build nuclear weapons the following year and called for action to halt the process.

But in a secret report shared with South Africa a few weeks later, Israel’s intelligence agency concluded that Iran was “not performing the activity necessary to produce weapons”. The report highlights the gulf between the public claims and rhetoric of top Israeli politicians and the assessments of Israel’s military and intelligence establishment.

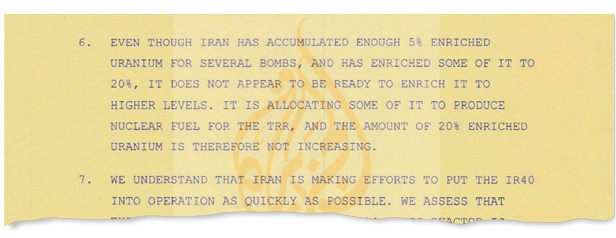

An extract from the document Photograph: The Guardian

An extract from the document Photograph: The Guardian

The disclosure comes as tensions between Israel and its staunchest ally, the US, have dramatically increased ahead of Netanyahu’s planned address to the US Congress on 3 March.

The White House fears the Israeli leader’s anticipated inflammatory rhetoric could damage sensitive negotiations between Tehran and the world’s six big powers over Iran’s nuclear programme. The deadline to agree on a framework is in late March, with the final settlement to come on 30 June. Netanyahu has vowed to block an agreement he claims would give Iran access to a nuclear weapons capability.

The US president, Barack Obama, will not meet Netanyahu during his visit, saying protocol precludes a meeting so close to next month’s general election in Israel.

The documents, almost all marked as confidential or top secret, span almost a decade of global intelligence traffic, from 2006 to December last year. It has been leaked to the al-Jazeera investigative unit and shared with the Guardian.

The papers include details of operations against al-Qaida, Islamic State and other terrorist organisations, but also the targeting of environmental activists.

The files reveal that:

• The CIA attempted to establish contact with Hamas in spite of a US ban.

• South Korean intelligence targeted the leader of Greenpeace.

• Barack Obama “threatened” the Palestinian president to withdraw a bid for recognition of Palestine at the UN.

• South African intelligence spied on Russia over a controversial $100m joint satellite deal.

The cache, which has been independently authenticated by the Guardian, mainly involves exchanges between South Africa’s intelligence agency and its counterparts around the world. It is not the entire volume of traffic but a selective leak.

One of the biggest hauls is from Mossad. But there are also documents from Russia’s FSB, which is responsible for counter-terrorism. Such leaks of Russian material are extremely rare.

Other spy agencies caught up in the trawl include those of the US, Britain, France, Jordan, the UAE, Oman and several African nations.

The scale of the leak, coming 20 months after US whistleblower Edward Snowden handed over tens of thousands of NSA and GCHQ documents to the Guardian, highlights the increasing inability of intelligence agencies to keep their secrets secure.

While the Snowden trove revealed the scale of technological surveillance, the latest spy cables deal with espionage at street level – known to the intelligence agencies as human intelligence, or “humint”. They include surveillance reports, inter-agency information trading, disinformation and backbiting, as well as evidence of infiltration, theft and blackmail.

The leaks show how Africa is becoming increasingly important for global espionage, with the US and other western states building up their presence on the continent and China expanding its economic influence. One serving intelligence officer told the Guardian: “South Africa is the El Dorado of espionage.”

Africa has also become caught up in the US, Israeli and British covert global campaigns to stem the spread of Iranian influence, tighten sanctions and block its nuclear programme.

The Mossad briefing about Iran’s nuclear programme in 2012 was in stark contrast to the alarmist tone set by Netanyahu, who has long presented the Iranian nuclear programme as an existential threat to Israel and a huge risk to world security. The Israeli prime minister told the UN: “By next spring, at most by next summer, at current enrichment rates, they will have finished the medium enrichment and move on to the final stage. From there, it’s only a few months, possibly a few weeks before they get enough enriched uranium for the first bomb.”

He said his information was not based on secret information or military intelligence but International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) reports.

Behind the scenes, Mossad took a different view. In a report shared with South African spies on 22 October 2012 – but likely written earlier – it conceded that Iran was “working to close gaps in areas that appear legitimate, such as enrichment reactors, which will reduce the time required to produce weapons from the time the instruction is actually given”.

But the report also states that Iran “does not appear to be ready” to enrich uranium to the higher levels necessary for nuclear weapons. To build a bomb requires enrichment to 90%. Mossad estimated that Iran then had “about 100kg of material enriched to 20%” (which was later diluted or converted under the terms of the 2013 Geneva agreement). Iran has always said it is developing a nuclear programme for civilian energy purposes.

Last week, Netanyahu’s office repeated the claim that “Iran is closer than ever today to obtaining enriched material for a nuclear bomb” in a statement in response to an IAEA report.

A senior Israeli government official said there was no contradiction between Netanyahu’s statements on the Iranian nuclear threat and “the quotes in your story – allegedly from Israeli intelligence”. Both the prime minister and Mossad said Iran was enriching uranium in order to produce weapons, he added.

“Israel believes the proposed nuclear deal with Iran is a bad deal, for it enables the world’s foremost terror state to create capabilities to produce the elements necessary for a nuclear bomb,” he said.

However, Mossad had been at odds with Netanyahu on Iran before. The former Mossad chief Meir Dagan, who left office in December 2010, let it be known that he had opposed an order from Netanyahu to prepare a military attack on Iran.

Other members of Israel’s security establishment were riled by Netanyahu’s rhetoric on the Iranian nuclear threat and his advocacy of military confrontation. In April 2012, a former head of Shin Bet, Israel’s internal security agency, accused Netanyahu of “messianic” political leadership for pressing for military action, saying he and the then defence minister, Ehud Barak, were misleading the public on the Iran issue. Benny Gantz, the Israeli military chief of staff, said decisions on tackling Iran “must be made carefully, out of historic responsibility but without hysteria”.

There were also suspicions in Washington that Netanyahu was seeking to bounce Obama into taking a more hawkish line on Iran.

A few days before Netanyahu’s speech to the UN, the then US defence secretary, Leon Panetta, accused the Israeli prime minister of trying to force the US into a corner. “The fact is … presidents of the United States, prime ministers of Israel or any other country … don’t have, you know, a bunch of little red lines that determine their decisions,” he said.

“What they have are facts that are presented to them about what a country is up to, and then they weigh what kind of action is needed in order to deal with that situation. I mean, that’s the real world. Red lines are kind of political arguments that are used to try to put people in a corner.”

Spread the word