Annie Parker remembers the day she brought her son Alex Bailey home.

He wasn’t a newborn swaddled in a baby blanket; he was a frightened 12-year-old foster child with whom she had started to develop an emotional bond.

“You’re gonna be my mama,” she remembers him saying happily.

A few hours after he arrived, however, she was startled by a commotion in one of the bedrooms and rushed inside to check. Alex was crying and banging his head against the headboard of his bed.

His behavior was disturbing, but it was not a complete surprise to Parker. As his foster-care mother, she had visited him at Riveredge Hospital, a Forest Park psychiatric facility.

Twenty years later, Parker, 72, continues to be flustered about the behavior of the son she adopted in 1998 and loves as if he were her biological child. Bailey, now 32, has been arrested and charged 34 times as an adult, mostly for minor crimes like retail theft.

He was locked up in Cook County Jail in July after his latest arrest.

Parker, a home care worker, feels overwhelmed by years of trying to solve a problem no parent can fix alone: How to keep her mentally ill son from cycling in and out of jail.

On average, about 2,000 of the jail’s 9,000 detainees are living with at least one mental illness, making Cook County Jail among the largest psychiatric facilities in the nation.

Like Bailey, most detainees funnel into the jail from ZIP codes on Chicago’s South and West sides, and the majority-black south suburbs, where mental health services are in short supply. They are part of what can be described as a neighborhood-to-jail pipeline.

About 70 percent of the jail population is African-American.

“There is an injustice inherent in our criminal justice system here,” says Cara Smith, executive director of Cook County Jail, commenting on whether the detainees are part of a neighborhood pipeline.

Addressing mental health issues before people are incarcerated should be the solution, but it isn’t, experts say, because of a lack of services in the very communities from which most of these inmates come. The problem, however, is citywide. Chicago’s patchwork mental health safety net has been fraying for years, and now people are falling through the holes, according to advocates, who raised the issue during the recent mayoral election.

Criminalizing mental illness is costly, inhumane and counterproductive, they argue. On average it costs $143 a day to incarcerate someone who is not mentally ill, but twice as much if the individual has a psychiatric condition and requires doctor’s care, medication and extra security. Experts say the money used to lock people up could be better spent helping people get the mental health and other social services they need to live productive, meaningful lives.

Incarceration can also exacerbate psychiatric illness, especially when detainees are placed in segregation.

Smith sees people like Bailey circling through the revolving doors of the county’s criminal justice system every day. Many of them have committed so-called crimes of survival.

“These are cases people should care about,” she says, “because I don’t know how being in jail is a good answer for this type of crime.”

From foster care to jail

Bailey’s path to incarceration included several foster-care placements. It’s not an unusual route, says Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart, who is responsible for the facility.

Bailey lived with a long-term foster-care family for eight years before he was briefly placed with a second family, and then a third. He moved in with Parker in June 1995.

He had been diagnosed with depression and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Bailey could not be reached for comment because jail officials would not allow The Chicago Reporter to interview him without the permission of his lawyers. The Public Defender’s Office, which represented him, said it would not approve an interview because Bailey’s case was pending.

According to school records provided by Parker, Bailey was categorized as being TMH, shorthand for trainable mentally handicapped. He attended classes for students with emotional and behavioral disorders and severe cognitive delays.

“Alex is functioning at an overall cognitive level commensurate with a 5½- to 6-year-old youngster,” according to school records dated Aug. 8, 1995, when Alex was 12. “He appears emotionally very fragile.”

The documents paint a gloomy picture of his psychological state: “He hears voices. He cried during reading because he can’t read.”

As a teenager, Bailey worked a series of fast-food jobs. When he was 18, his performance at a White Castle on North Milwaukee Avenue was considered satisfactory, even outstanding for some tasks. Except when it came to reading his shift schedule, his boss says in a report to the Illinois Office of Rehabilitation Services, which is now a division of the Department of Human Services.

Bailey had already quit the White Castle job when the report was written.

Soon after, he started stealing and getting arrested.

About four years ago, Parker toted his records to court in a worn, three-ring red binder to show attorneys and judges documentation of his troubled history. But she says no one seemed interested.

“He’s persistent on trying to do things, but he’ll be doing the wrong things. He’s not a dangerous person. He’s a sweetheart,” says Parker, throwing up her hands in frustration. “He needs help, and I can’t seem to get it through them people’s heads that that’s what he needs.”

In July, Bailey hurled insults at a criminal court judge during a court appearance after he was arrested for stealing liquor. The judge hit him with a contempt charge.

In jail, many find treatment

Photo by Penny Wang / Social Justice News Nexus

Detainees wait in a holding area near the intake section at Cook County Jail, which has become one of the nation’s largest psychiatric facilities.

Loud voices echo against grimy walls in the intake section of the Cook County Jail on a weekday morning last December. New arrivals wait in caged holding areas or on long, worn benches.

Elli Petacque Montgomery, a licensed social worker and deputy director of mental health policy and advocacy at the sheriff’s office, supervises the intake process for new detainees. Before being shipped out to bond court, each person under arrest is briefly interviewed to collect information used to determine if mental illness may have played a role.

Many are there for committing survival crimes, which include retail theft, criminal trespass to property and minor drug crimes — offenses involving people trying to get something to eat, find a place to sleep and just get by.

They are asked about medications, psychiatric diagnoses and symptoms such as “racing thoughts,” among other things. An intake form also records whether they are homeless, have health insurance or use illegal drugs.

By 11 o’clock, 36 men have been processed, including three sitting on a bench nearby. One is a fragile-looking elderly black man with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder who told Montgomery he had run out of one of his anti-psychotic medications.

“When they can’t get medication, they ‘self-medicate’ [with alcohol and drugs] to drown out the voices,” Montgomery says. She turns toward the bench and nods. “That’s someone I have some concern about.”

There are other stories this day:

A man diagnosed with schizophrenia has been arrested for retail theft of less than $100. He is homeless with a history of taking illegal drugs. He hears voices and sees things that aren’t there, Montgomery says.

A man diagnosed with schizophrenia reports having hallucinations of graveyards. He says he tried to kill himself multiple times and hears voices that tell him to hurt himself and commit crimes. He is an alcoholic who also uses cocaine and marijuana to self-medicate.

An HIV-positive man who is diagnosed with bipolar disorder arrived in jail “bordering on the color green,” Montgomery says. He has been shooting heroin for so long the veins in his arms have collapsed. Montgomery remembers him going through intake a year ago.

“This is a place where poverty, lack of education, homelessness, drug addiction mental illness all sort of come crashing together,” Smith says.

Mental illnesses run the gamut from mild to severe — from anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

“But it costs money to get someone well,” Montgomery says. “You can’t do therapy in jail. You can’t do true intensive treatment in jail. … We do pretty good. But we don’t give them the treatment they really need, compared to a therapeutic environment.”

Closures worsen problem

Photo by Grace Donnelly

This storefront at 2354 N. Milwaukee Ave. in Logan Square was the former home of the Northwest Mental Health Clinic — one of six shuttered by the city in 2012. A gourmet macaroni and cheese restaurant is slated to open in the space this summer.

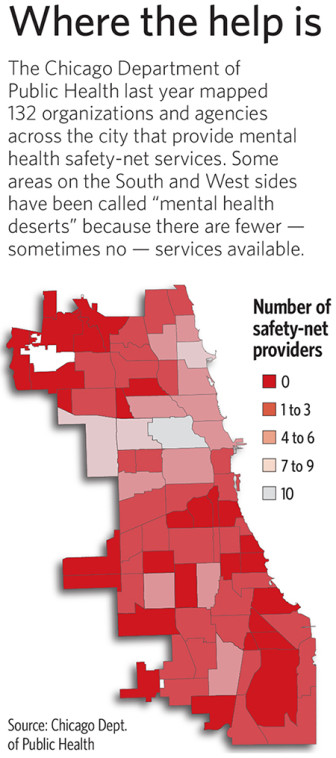

In Cook County, vast swaths of the South and West sides and south suburbs are considered “mental health deserts,” areas where such services are scarce.

These are communities where negative social factors such as unemployment, discrimination and poor education tend to cluster, and these negative social factors frequently lead to poor mental health, says Dr. Ruth Shim, a psychiatrist in New York and expert on mental health disparities.

“Things we consider commonplace in our communities — like violence and crime — are really damaging to our mental health,” Shim says. “We take that for granted but people act out. Instead of addressing mental health problems, we put people in jail.”

Mental health deserts make it difficult for people who live in those communities to get the help they need, says University of Chicago law professor Mark Heyrman, chairman of the public policy committee of Mental Health America of Illinois.

“It can take several bus rides to get to places where there are services,” he told a recent forum on mental health issues at Columbia College. “And that’s a serious problem.”

In an effort to find community-based services for detainees when they are released, the sheriff’s office started mapping facilities in the county that provide mental health services.

“The thing that is startling, when we started mapping it out, is the absolute lack of services when you hit 75th Street south to the border of Will County,” Dart says. “It’s absolutely stunning how few services are out there. It just screams out when you look at the map.”

When hundreds of state psychiatric hospital beds were taken out of service decades ago in an effort to shift patients into community-based care, sufficient funding for community programs never followed, says Heather O’Donnell, vice president of advocacy for Thresholds, a large social service provider.

Illinois “de-institutionalized nearly 35,000 people in the 1960s and 1970s,” she says, “and we never fully invested in a community-based mental health treatment system and affordable housing. The state cut $113 million out of community mental health services. At the same time, utilization of emergency psychiatric services rose 18 percent.”

From 2009 to 2011, Illinois was the state with the fourth-largest cuts in mental health spending with budget cuts of $113.7 million, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

Psychiatrists play a critical role in providing services because they prescribe and monitor medications.

Cristina Villarreal, director of public affairs for the Chicago Department of Public Health, says currently one full-time and one part-time psychiatrist staff the city’s six mental health clinics, which have a total patient caseload of almost 1,000. A temporary psychiatrist works part time.

The city raised the salary of psychiatrists last October to attract qualified candidates and retain their current doctors. And the department aims to hire six full-time psychiatrists and additional staff, she says, adding that the goal is to help residents avoid involvement with the criminal justice system.

Shim says the closure of half of the city’s dozen public mental health clinics in 2012 likely exacerbated problems in underserved communities.

“I think that Chicago stands out because there are clear places where there are high levels of poverty, high levels of violence, and those communities need more intervention and mental health support,” she says.

Nneka Jones, a psychologist in charge of mental health strategy at the jail, says access to mental health services in close proximity to one’s home is critical.

“I think that’s the biggest challenge: access,” she says. “There is a shortage of inpatient, outpatient and residential care, short- and long-term.”

Mental health and social service agencies, private and public, are under increasing financial strain. Cuts proposed by Gov. Bruce Rauner in next fiscal year’s state budget raise even more uncertainty about access to services.

Mayor Rahm Emanuel and city health officials came under fire when they closed the six mental health clinics in 2012. Critics blasted the city, saying some patients ended up jailed, homeless or dead as a result. Dart says the jail saw an increase in detainees from those areas after the mental health clinics closed.

Back in August, then-health commissioner Dr. Bechara Choucair told a City Council health committee hearing that services had not been cutback, only consolidated.

The University of Chicago’s Heyrman says his concern is less about the closures and more about the lack of a viable plan to ensure a mental health safety net, even if the city is not directly delivering the care. “The city has never figured out what the priorities should be,” he says. “The city should make sure people within its are getting appropriate care.”

Every day, 30 people who have been diagnosed with mental illness are discharged from the jail.

To help reduce recidivism and improve community safety, Chicago plans to launch a new initiative in March with the Cook County Sheriff’s Office to link every Chicagoan released from the jail who needs mental health treatment to a community provider, Villarreal says.

In August 2014, the county Department of Corrections opened a mental health transition center for high-functioning inmates who are serving their prison time at the jail and will soon be released. It sits on the site of the jail’s former boot camp nearby.

Inmates receive therapy for the first six weeks of the program, including training in problem-solving skills. During the final six weeks, they also receive vocational training.

Officials are planning to add a residential division in the near future. The goal is to help inmates obtain the skills they need to successfully re-integrate into their communities.

Many of the inmates are poor and uninsured, says Ben Breit, director of strategic communications in the sheriff’s office, who says officials are facilitating sign up for Medicaid to ensure health coverage post-incarceration.

Thousands of current and former detainees and inmates have applied.

“To make the strides we need to make, we’re talking about huge shifts in the way we do things,” Shim says. “But providing people with serious mental illnesses and substance-use disorders early access to mental health services in their communities instead of in jails and prisons is a start.”

‘I wanna be free’

Bailey received counseling at Mount Sinai Hospital when he was a minor. But Parker says when he got older and he wasn’t in the foster care system anymore, “Voila, things changed.”

She tried to help him get Social Security disability benefits, but whenever he needed to follow-up, he was locked up.

“He’s never around to get the interview,” she says.

Bailey was arrested in April 2014 after a security guard observed him leaving a Target on the North Side with nine bottles of Patrón tequila worth $191.61 that he hadn’t purchased.

He was found guilty and received credit for 182 days of time served. But after he was transported to the prison and processed, he was released because his sentence did not exceed the time he had already spent behind bars — a situation known as a “turnaround,” Smith says.

In July, he stole liquor from a Jewel store on West Canal Street and was arrested again.

“You have to really wonder how, under anybody’s analysis, jail is a good idea for people suffering from mental illness and committing crimes for which there is no real identifiable victim,” she says, adding that the store did not lose a penny because Bailey was caught.

During a mental health screening conducted for the courts in May 2010, Bailey reported a 2003 psychiatric hospitalization at St. Elizabeth Hospital where he was prescribed medication for depression and anxiety and stayed for four months. He also reported that he participated in a hospital outpatient program for eight months, but he says he didn’t know the name of his doctor or his medications.

According to the same screening report, “The defendant also reports severe alcohol use for the past 10 years, however, has never been in treatment.”

In 2010, Bailey tried to hang himself, the first of two suicide attempts in the jail lockup. When correctional officers stopped his second attempt last year, he told them: “I wanna die. I wanna be free.”

Bailey’s problems have worn down his adopted mother, who says she cannot afford any more collect calls from the jail or trips to court. She also stopped visiting him in jail. On March 23, Alex was sentenced to five years in prison.

Yet, she remains devoted to the young man she bonded with when he was a troubled boy in need of a stable home. When he gets out of prison, she says he is welcome to move back into her West Side home. And she will try to help him.

“He doesn’t need to be locked up,” Parker says. “He needs to be someplace where he can get help.”

This story was produced as part of the Social Justice News Nexus, an initiative at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism that brings together reporters, community watchdogs and journalism students to cover issues that affect Chicago. Learn more at sjnnchicago.org. The Social Justice News Nexus is supported by the Robert R. McCormick Foundation.

Deborah Shelton is the managing editor at The Chicago Reporter. Email her at dshelton@chicagoreporter.com.

Spread the word