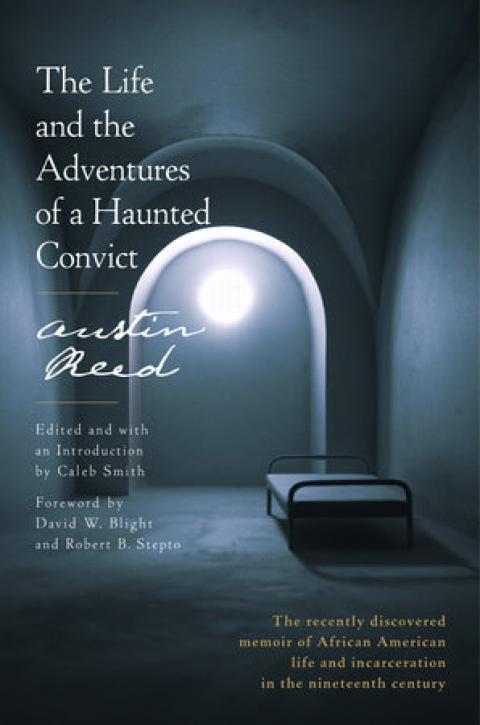

The Life and the Adventures of a Haunted Convict

By Austin Reed

Foreword by David W. Blight and Robert B. Stepto

Edited by Caleb Smith

Random House

ISBN 9780812997095

Austin Reed’s The Life and the Adventures of a Haunted Convict is startling, instructive, and disquieting. Unearthed in a 2009 Rochester, New York, estate sale and acquired by Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book Library, it is a hitherto-unknown confessional by a “free” nineteenth-century black New Yorker who spent decades of his life imprisoned. Reed’s memoir introduces readers to the misdeeds and tragedies of a career criminal who began his misadventures before the age of ten and whose first major crime was to set fire to the house of the white man to whom he had been unwillingly indentured.

Reed worked on Haunted Convict intermittently during his long years of confinement, as well as during brief interludes of freedom. Never entirely finished or published—in fact, unknown in its day—it provides a perfect example of problematic encounters with black captivity: How to be enlightened without treating as entertainment the consumption of black suffering? A historical artifact, the book holds both archive and mirror for the present antagonisms about racism, policing, and mass incarceration, contributing to the ongoing exploration and debates concerning American democracy and racial identity built upon black captivity.

At the same time, Reed’s book in some ways vexes our desire for writing by nineteenth-century blacks to conform to the prevailing narrative arc of American slavery. Although Haunted Convict undoubtedly informs us about the critical period when American racially fashioned slavery began its mutation into the carceral state, Reed, for better or worse, is authentically his own person. His long imprisonment rendered him both a grief-stricken informant and political isolate. He completed his memoir in 1858, the same year that John Brown visited abolitionist Frederick Douglass in Rochester to propose the Harper’s Ferry slave insurrection (Douglass declined to participate). Yet Reed shows no awareness of the radical racial politics occurring in his hometown and dominating the era. Where we might wish that he would contextualize his narrative in relation to other nineteenth-century stories of slavery, he instead draws inspiration from what is most familiar to him: popular and populist tales of moral reform and his relationships with the white men who tormented or comforted him during his lengthy detentions and periodic escapes.

Reed thus challenges us to take him on his own terms—to accept that he need not be representational even as he represents suffering under captivity. His suffocating, brutal world of the penitentiary crosses generations and centuries, and his sense of genre does nothing to obscure the violence and racism of inmates, guards, and administrators. All of this makes Life and Adventures of a Haunted Convict welcome for its eerie, yet sadly familiar, revelations.

Childhood Trauma

Editor Caleb Smith skillfully introduces both Reed’s life and nineteenth-century American prisons. In their foreword, David W. Blight and Robert B. Stepto insightfully observe that Reed writes “about being orphaned from his home and his race” in a memoir that “tells of Reed’s search for family.”

Austin Reed was born to Maria and Burrell Reed between 1825 and 1827 (according to Reed; the House of Refuge registers his birth as 1823). Of mixed racial heritage—Reed was often identified as “mulatto” in official court and prison paperwork—the Reeds were members of the growing community of free blacks in Rochester. They likely named their son after Austin Steward, a family friend and fugitive slave turned abolitionist. Although the memory of his dead father’s moral pleas shadows Reed’s life, Haunted Convict surprisingly makes no mention of his father’s friend, Reed’s namesake and likely godfather, Steward, an influential leader in Rochester’s black communities. It seems odd that Reed’s memoir contains no mention of Steward, or any other black father figures to whom Reed could have turned for guidance in a patriarchal era in which black community established and protected black freedom. When Reed’s father died in 1828, Steward and other leaders of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church his father cofounded helped Maria Reed to liquidate and administer the estate left by her husband. As a result, the Reeds were able to keep their middle-class house, where Maria died in 1865. In most other respects, though, the family was left destitute. Haunted Convict disappears Steward and Rochester’s black community and its AME church, which was so active in the abolitionist movement that it offered its basement for Frederick Douglass to produce the weekly anti-slavery paper, The North Star.

One might be tempted to say that the death of Reed’s father dissipated all black role models and communal ties, including a bold church that confronted the evil of slavery. Perhaps even more saliently, Reed’s inattentiveness to an identity shaped by abolitionism—and near absence of free and prosperous blacks—likely reflects his childhood poverty and long-term institutionalization, which began early in his youth. Both experiences effectively left him exiled from the world of educated abolitionists that should have been his birthright, a tragic turn that—as in Solomon Northup’s Twelve Years a Slave—highlights the precariousness of even prosperous free blacks in the nineteenth century.

In 1832 Reed’s mother placed him into indentured labor. Reed was prone to misbehavior; he had even threatened to split his mother’s head with an axe if she whipped him for having destroyed some fruit trees on another property. Still, we can imagine that indenturing her young child was an agonizing act of financial desperation and maternal exhaustion if not depression. Reed describes how his mother’s despair with poverty, children, and an incorrigible truant leads her to attempt suicide. A young child, Reed is forced to leave home to serve as “apprentice” to a white family, whose patriarch flogs him. After being shackled and beaten, Reed runs away and returns home. His older sister helps him to plot an assassination of the landowner. While he fails to kill his tormentor, Reed does set fire to the house. He may have been as young as six at the time, ten at the oldest. Tried for arson and assault in 1833, he was sentenced to the New York City House of Refuge until he turned twenty-one.

Racial Winners and Losers

The House of Refuge was funded by wealthy patrons concerned with the moral character and labor of New York’s burgeoning wave of new immigrants, many of whom were poor Irish or Germans. The House of Refuge functioned as a social project aimed at reforming the newly coined category of “juvenile delinquents” into compliant laborers while socializing these new immigrants into segregation and the privileges of whiteness. As part of their reformation, young prisoners were given a basic education, which is how Reed learned to read and write.

However, the House of Refuge was anything but humane: staff routinely tortured children with the cat-o’-nine-tails, a whip of rope and metal; detention in dungeons; simulated drowning in “showering baths” (waterboarding); starving with only bread and water; and prolonged isolation in solitary confinement. With the braggadocio of the child or captive, Reed and his friends boast of their ability to stoically endure abuse, taking pride in their emotional and mental defiance in the face of terrible physical pain. When they tease one of their friends, Mike, for fainting while being whipped, he retorts, “It would make an angel bow too, if he had received the like.”

These early experiments in the use of corporal punishment-as-torture to induce “moral reformation” in prisoners illustrate the development of technologies that would define U.S. treatment of prisoners as well as political and military detainees. (Reed derisively notes that brutality made the youths indifferent and violent.) Prison reformers, Reed writes, led to the banning of techniques such as whipping and showering baths that at times killed inmates. Such tactics of discipline, control, and revenge later reappear in “enhanced interrogation.”

Reed’s text lacks the political sensibility of an anti-racist race consciousness. Although full of homicidal rage at the horrors of his captivity, Reed directs his wrath only against corrupt and brutal white prison authorities and black criminals. His indifference toward or contempt for other black men, generally renders them invisible. When other black captives are mentioned, it is almost always as a foil, a means for highlighting Reed’s worthy inclusion within and embrace by a fugitive white society. Despite his incarceration, whites outside of prison perceive Reed as a “good negro,” his mixed race and youth making him capable of reform—unlike the lost causes of darker-skinned black men and boys. As such, Reed’s narrative is more about race than anti-racism: he demonstrates to his presumably white audience how he navigates a white-dominant environment in order to survive and remains at the service of deserving whites while avenging the indignities of prison abuse.

Between 1825 and 1855, 63 percent of the children held captive in the House of Refuge were Irish. In the 1830s, when Reed entered the House of Refuge, proslavery pundits actively sought to prevent alliances between white European immigrants and black Americans. They did so by arguing that, unlike blacks, who were biologically deficient, European immigrants were only culturally deficient and could overcome these shortcomings through assimilation into mainstream white American culture. In other words, distance from both the homeland and from blacks was the way to scale the ladder of America’s class structure.

Against this grain, Irish boys become Reed’s closest associates during his childhood incarceration. With their assistance, he escapes on multiple occasions from the House of Refuge. Each time, the white boys, and Reed, quickly change out of prison garb in order to decriminalize their whiteness. Reed, a free colored or mulatto youth of lighter complexion, derives some benefits through their company, as well as from their allegiances and family ties. The white Irish families who harbor the escapees are able to face down and deceive the white police and publicly rail against the injustice of the incarceration and abuse of their children. Although marginalized in their own right—as poor immigrants—they still possess an agency made possible because they cannot be confused for a black family-as-mob.

Reed romanticizes these Irish families and their children; in a sense, he becomes one of the Irish boys by proxy, joining in their denunciations and rebellions against and escapes from the House of Refuge. He loves them for enabling this act of belonging, and they love him back. Reed has found his surrogate family, and he protects it. In decades of interactions with them, Reed records not one racist word they utter or racial bias that they practice. Without connections to a black family, community, or church, his views of racism focus on personal insult rather than structures of repression and collective struggles. He downplays the differential treatment and harsher punishment he experiences at the hands of white prison guards.

Reed has no mirror to authenticate the value of his existence as a black person, no wiser role model or friend to offer a meaningful racial context for his incarceration and abuse or to explain how tenuous can be alliances with—and protections offered by—whites. Reed predicts that Irish Catholics, historically persecuted and preyed upon, will rise. And they did: to become presidents, senators, mayors, and police chiefs tasked with regulating black lives in Boston, New York, and Chicago. New York’s white, proslavery Democratic Party campaigned against Abraham Lincoln by warning Irish and German communities that his election would open a flood of emancipated slaves to compete in New York’s labor market. During the 1863 draft riots, following a federal lottery in which affluent whites could buy themselves out of the carnage of the Civil War for $300, Irish immigrants rioted first against the government, then against white abolitionists, and most violently against black men, women, and children, destroying a black orphanage, lynching and driving blacks out of their homes and the residential and public life of lower and midtown Manhattan as they fled to Brooklyn and Harlem.

Gender Heroism and Disabilities

Haunted Convict is sprinkled with Reed’s homoerotic observations of the white Irish boys with whom he is detained. He often notes their beautiful and feminine features. His memoir makes no mention of his own physical attractiveness—obviously altered by torture, particularly flogging—although it highlights his intellect and character. His value is enhanced relative to the non-mulatto black criminals he encounters, black boys and men whom he describes as beastly. (Although the Bible is a constant companion, Reed fails to recall Song of Songs 1:5, “I am black but comely.”) The contrast Reed draws between himself and other criminal black males helps to whiten him for his reader, and for himself. For example, when Reed visits Thom King—one of his tormentors in the House of Refuge, who is on his deathbed following an injury from falling timber—Reed writes, “The impudent and black infernal black hearted nigger had the impudence to stretch out his black paw.”

Later, after he has been released from the House of Refuge, Reed shoots a black Canadian seaman, Jones, to prevent him from raping a white girl. He describes the assailant as having “clumsy hands,” a “heavy arm,” and “heavy voice”—racial stereotypes of the black male. Recounting his rescue of a young white woman who turns to prostitution after being disgraced and abandoned by a white suitor who pretends to marry her, Reed distinguishes himself from black and white sexual predators alike. The young Reed saves and restores rather than despoils white female virtue. His abhorrence of alcohol, and counseling of a wealthy white man to refrain from drinking and reunite with his estranged wife, is another testimony to his value as a moral citizen.

Reed has few opportunities to cultivate friendships of racial solidarity. During his time in Auburn State Prison, which he entered as a teen and where he stayed into his adult years, only 10 percent of the incarcerated were black. Auburn, an experiment in the “congregate” or “silent” prison system, forbade the incarcerated to speak to one another; they could only read the Bible. Prisoner-to-prisoner interactions were few and severely punished if discovered.

Years of abuse, starvation, and deprivation probably caused Reed to suffer impaired judgment, what today would be called an executive functioning disorder or mental illness. Even by the standards of the day, Reed’s torture was extreme, though certainly not atypical. “Horrors, horrors, horrors, eternal horror of horrors,” he writes of being severely whipped and then locked in stocks in a dark dungeon, only one of the many torments he endures. His jailors—whom he calls by ironic and macabre names such as “Mr. Hard Heart, Mr. No Feelings. Mr. Cruel Heart, Mr. Demon, Mr. Fiend, Mr. Love Torture, Mr. Tyrant”—frequently threaten to murder him, taking sadist pleasure in hearing him sob and beg for a lesser punishment.

When he is later transferred from Auburn to Clinton State Prison, his physical condition is so disturbing that officers suggest a formal investigation, which never happens. As a child, whenever he escapes from the House of Refuge, Reed returns or desires to return to old neighborhoods even though he knows that police will hunt for him there. At thirteen he has access to $100 stolen by a white prostitute but only takes $5 from her, giving none to his impoverished family. He then follows her instructions to plead guilty to her theft and thereby rescues her from imprisonment. During sentencing, Reed lies about his age to avoid the House of Refuge, and so is sent instead to an adult prison, Auburn. With limited understanding or control of his emotions, he cannot stay out of crime and prison. His imagination, shaped by traumatic experiences, drives him toward freedom but not away from prison. He pursues a confinement where he will not be constantly haunted and damaged, but none such exists.

Reed rightly observes that his incarceration—often solitary—in the House of Refuge, Clinton, and Auburn causes his deterioration. Not only is his body repeatedly tortured and deprived of nourishment, he is denied intellectual, emotional, and spiritual stimulation and connection. As Lisa Guenther notes in Solitary Confinement: Social Death and Its Afterlives (2013), extreme isolation diminishes or destroys human capacity for relationships and social development, prisoners become more depressed or psychotic, and “the intersubjective basis for their concrete personhood” is undermined by the absence of everyday experience or intimacy with others. In January President Barack Obama banned solitary confinement for juveniles or youths in federal prisons due to the resulting psychological devastation and self-harm.

Legacy

As Smith informs us, Reed likely finishes writing Haunted Convict around 1859, just before he is transferred from Auburn to Clinton State Prison, where he encounters more sympathetic guards, who permit him to seek a pardon from the governor. The pardon is eventually granted in 1876. Following the Civil War, Reed disappears into anonymity and returns to Rochester, as he repeatedly did after escape or release from prison.

It is not clear if Reed sought to publish his memoir. He imitates the style and plot elements of bestselling novels he knew of, despite railing against their “immorality.” Perhaps Reed would have relished the largely white and propertied literary audience of the less incendiary nineteenth-century abolitionist literature and memoirs: Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852); Douglass’s My Bondage and My Freedom (1855, a revision of his 1845 Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written By Himself); and Harriet Jacobs’s sanitized Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861). Yet he doesn’t seek crossover appeal by seriously tackling the connections between slavery and penal captivity. With no political reputation or following to maintain, Reed’s candor about his crimes and his channeling of anti-black racism reveal a social and political isolation rooted in the intrinsically vulnerable and unsettled nature of being a free mulatto in the nineteenth century who depended upon race-mixing alliances to resist penal culture. Survival, not slavery, is the pressing issue of his life. He focuses his battles on the indignities foisted upon him through indenture and incarceration. Unfortunately, after the Civil War, penal captivity and slavery converged following the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment. Abolitionists were unable to prevent the reemergence of slavery through a bipartisan, interregional agreement to exploit convict prison labor—called “sweat labor”—in which blacks died at faster rates in the South than they had on plantations.

Today New York’s more than fifty correctional institutions include Attica, Auburn, Clinton, and Sing Sing—sites infamous for their horrific conditions. New York City’s Rikers Island juvenile jail facility replaces the function of the House of Refuge, which was burnt to the ground, allegedly by its young prisoners. In 2015 New York voted to ban solitary confinement for detainees under twenty-one years old at Rikers in response to the highly publicized case of Kalief Browder. Without money for bail, Browder, a black teen, was held for three years, mostly in solitary. He was accused of stealing a backpack but was never formally charged or tried. Browder was repeatedly, savagely beaten by Rikers guards and inmates and committed suicide after his release.

Reed and the children of his era suffered in similar ways. Yet they forged a community to fight isolation and torture through transgressions—winks, code, bragging, honor pacts, rebellions—that created familial care. This is an American legacy: the horror story and the resilience of captives. It is also the haunted lineage of Austin Reed.

Spread the word