Union elections are often close—but not at a pair of Brooklyn camera warehouses last fall. Three hundred workers at B&H, a popular video and photography equipment company, won their union election with an overwhelming majority.

How did B&H workers hold so strong even when their boss threatened mass firings? Behind the scenes, they got the organizing skills they needed from in-depth leadership training with the Laundry Workers Center.

The organizing got started when a few workers, fed up with long hours and discriminatory treatment, started meeting regularly after work to discussion conditions. Among them was Raul Pedraza, who has worked in the company’s Evergreen warehouse for six years.

The last straw came when a co-worker was fired. “We all agreed,” Pedraza said. “We are going to talk to Human Resources and tell them that we are sick of this.” They convinced everyone in the warehouse that day to stop work and go upstairs together to speak to the manager—who got very nervous.

But Pedraza and other leaders wanted to do more. “We were talking about doing an action outside the retail store,” he said, “but I said, ‘No, how are we going to do that, just us by ourselves? We need someone who is going to back us up.’”

That’s when the Laundry Workers Center came into the picture. Pedraza’s brother had worked in a laundry across the street from the Hot and Crusty deli, where the center helped workers form an independent union in 2012. He told Raul to get in touch with the center for help.

Leadership Institute

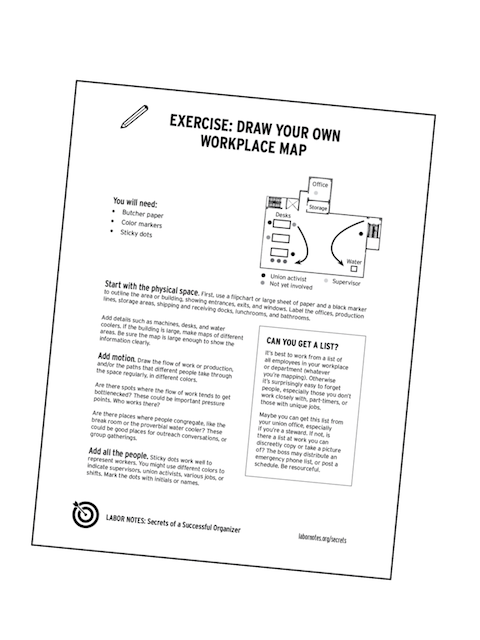

B&H workers drew a map to pool their knowledge, identify hazards, and pinpoint potential leaders in every department.

The Laundry Workers Center puts a big emphasis on developing workers’ organizing skills through training. It tailored a training for the Hot and Crusty workers, who eventually won their union through a creative, escalating campaign, profiled in the film “The Hand That Feeds.”

Mahoma López, a leader at the deli and now co-director of the center, remembers his first conversation with organizer Virgilio Aran. “He told us why it’s important to organize,” López said. Without organizing, even if you win back your stolen wages in court, “they will fire you, and you’ll go to some other place where you will be exploited.”

The center now runs a regular eight-week organizing training. The only requirement is that participants must intend to put the training into action. “You have to do something in your workplace or in your community,” says Co-Director Rosanna Rodríguez. “If you don’t commit to do this, we are not interested in you participating in the Leadership Institute.”

The institute teaches workers to identify leaders, recruit co-workers, and make a campaign plan. They learn about labor history, negotiating with the boss, and speaking to the media.

The program is designed to give participants the confidence to take action on the job. “It’s not going to be Rosanna or me,” says López. “They are the ones that have to be in front of the boss.”

But at B&H, the center faced a challenge of scale; it would need to quickly train hundreds of people.

To accommodate workers’ tight schedules, “we had to be creative,” said Rodríguez. Trainings took place after work, often in the nearby Laundry Worker Center office, with small groups of six to eight workers, sometimes running from 8 p.m. to 3 a.m.

Skills Into Practice

The training with the initial group of leaders began in September 2014, and one of their first steps was to map the workplace.

Health and safety soon emerged as urgent concerns. “We realized that all of the workers suffered from nosebleeds, headaches, and many had hurt their backs,” said López. “Many had hernias, loss of vision, neck pain. It really impacted us to see that workers were working in these conditions.”

Workers mapped where the hazards were worst. Then they used their map to identify leaders in each department and floor. “A leader is someone that others follow or respect,” said Rodríguez. “There is always someone who can bring along other workers.”

“Almost always,” adds López, “a leader is someone who speaks up on behalf of other workers.”

The B&H workers used this information to decide which co-workers should be their first priorities to recruit. Using the conversation skills they learned in the trainings, they invited each potential leader to an organizing meeting. As new workers got involved, they too were invited to the mobile institute, where they learned to recruit others and helped develop the campaign plan.

“Usually, the institute is eight weeks,” said Rodríguez, “but with the B&H workers, there were always new people joining and we would have to start from scratch.”

As part of their training, B&H workers went to rallies to support McDonald’s and Wendy’s workers and the Black Lives Matter movement. At first many were nervous, Pedraza said—but once they had some action experience under their belts, their fears diminished.

You can’t send people into war their first day, López explained. “It has to be a process where they are learning from other experiences of struggle. That way, the day they launch their campaign, it is something normal.”

Participating in other actions also helped build networks of solidarity that B&H workers drew on when they were ready to go public themselves.

Union Was the Goal

From the beginning, B&H workers identified a union as their organizing goal.

The LWC helped connect them to the United Steelworkers, and last July a USW organizer started supporting the drive. But the Laundry Workers Center continued to lead the leadership development process, building on the trust and relationships they had developed.

B&H workers launched their campaign publicly in October, picketing with supporters outside the warehouses and retail store.

Through one-on-one meetings with anti-union consultants and even threats of mass firings, workers stayed united. In fact, when workers were ordered off the job in one warehouse, workers in the other warehouse left their own jobs in solidarity. In November, they won their election 200 to 88.

They went on to organize the hidden warehouse underneath the Manhattan B&H retail store, where workers have three minutes to fulfill orders or risk being disciplined. This leads to the same types of health and safety problems that workers have reported in the Brooklyn warehouses, López said.

“The invoice goes to the basement,” explains Rodríguez, “and in three minutes, workers have to find the equipment, get it ready so it goes up to the person waiting. Everything looks perfect, but the ones doing the work are the workers in the basement.”

The training, López says, was crucial to the election wins. He believes that every worker who voted for the union had received organizing training through the leadership institute.

The elected bargaining committee is now in the process of negotiating a contract with B&H.

What keeps Pedraza going is still the same. He feels the younger workers at B&H are like his own kids. It’s difficult to see them working long hours and getting worn out.

“I tell them, ‘I don’t want what happened to me happen to you,’” he said. “My kids never saw me. I went to work, and then came home to sleep. You don’t know what you will lose.

"Now is the time for us to improve all this. We are not going to stop until we get there.”

Quotes in this story have been translated from Spanish.

Learn to map your own workplace with Secrets of a Successful Organizer. Buy the book and download free handouts like Draw Your Own Workplace Map at labornotes.org/secrets

A version of this article appeared in Labor Notes #447, June 2016. Don't miss an issue, subscribe today.

Spread the word