For much of this election cycle, voting rights advocates have been playing defense. Seventeen states have enacted new curbs on voting, including voter ID laws, that weren’t in place for the last presidential election. These new laws build on a rash of electoral restrictions enacted in in 22 states between 2010 and 2012, and follow on the Supreme Court’s 2013 ruling to invalidate key parts of the historic Voting Rights Act of 1965.

All this has made defending the right to vote from further erosion a central preoccupation for advocates of democracy. But advancing voting rights is about more than just blocking new restrictions and warily protecting the franchise. It’s about expanding access to the polls. A good voting rights offense—one that equitably broadens mass participation—is especially important for voting populations of color and in poverty.

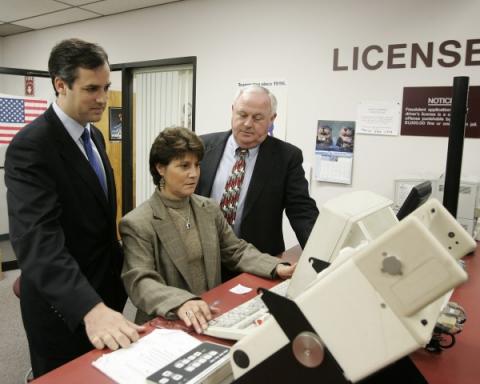

Too often, states disenfranchise these voters not by actively limiting their access to the polls, but by failing to implement federal laws aimed at adding them to the rolls. The main tool to expand voter expansion is the National Voter Registration Act of 1993. The linchpin of this law was its “Motor Voter” component. Under that provision—Section 5—states were required to integrate the process of voter registration with that of applying for a driver’s license.

The goal was to boost political participation by linking voter registration to a widespread aspect of daily life, namely getting a license. Yet, in the 23 years that this policy has been in effect, the number of voter registration applications processed at motor vehicle agencies (DMVs) has remained stagnant, despite significant growth in the voting age population. This is because many states are simply not complying with the law. One estimate suggests that nearly 18 million additional voter registration forms would be processed biannually at DMVs if states did even a moderately better job of signing people up to vote.

Compounding this shortcoming is another missed opportunity to strengthen our democracy: the failed implementation of a lesser known aspect of the National Voter Registration Act that required public assistance agencies to serve as voter registration sites. This provision—Section 7—mandated that states offer voter registration services to every person applying for or renewing public assistance benefits.

The objective was to ensure an equitable expansion of the electorate by reaching beyond DMVs to the disproportionately poor and minority populations that sometimes have difficulties obtaining a driver’s license. Because of Section 7, public assistance agencies that offer food, health coverage, and other life necessities must now also be equipped to register voters by providing registration forms, helping people fill them out and sending them to the necessary officials. These services could help low-income Americans overcome the significant barriers they face in registering to vote. However, the potential of this law is largely unfulfilled, due in large part to the racial bias and partisan politics that have hampered its implementation.

In 1993, voting rights advocates had high hopes that Section 7 would catalyze political engagement among low-income voters. And while the NVRA did make the electorate slightly more representative, the initial expectations that accompanied the law have not been realized. For example, in 1995 and 1996, more than two-and-a-half million Americans submitted voter registration applications to public assistance agencies. But in 1997, those numbers began to plummet, and by 2005 state public assistance agencies registered just over half a million people.

After 2006, voting rights advocates sought to reverse this decline by suing some of the states that were the least compliant with Section 7. The suits did bear some fruit. During the 2014 election cycle, approximately 1.6 million Americans submitted voter registration forms at public assistance agencies. Nevertheless, this represents only a small slice of the more than 50 million Americans receiving help from the government each year.

Why aren’t states registering more low-income people? Diminished levels of voter registration at social service agencies are not, as some might speculate, because low-income people are already registered, or because they do not want to vote. My own analysis of agency-based registration between 1995 and 2012 shows that partisanship and race were the biggest factors determining states’ compliance with the requirements of Section 7.

When a Democratic president occupied the White House, states were more likely to comply. Similarly, when Republicans were in control of the legislature, states were substantially less likely to register voters via social service agencies.

State compliance also decreased in direct proportion to the size of the black population. As the black proportion of state residents increased, compliance went down. Compliance also decreased when whites had higher rates of voter registration relative to African Americans and other people of color. Essentially, increased black populations and lower levels of political engagement among those populations discouraged compliance with Section 7.

Ordinary government employees—the folks who work at public assistance agencies—were also vital players. This is important because even if politicians support compliance by ensuring that registration forms are readily available or by enforcing oversight, people who work at the “street level” must ultimately ask those who walk through their doors if they would like to register. Compliance was significantly higher when those people were African American. This is not surprising given that black government employees have a well-established history of viewing their work through political lenses.

African Americans play a substantial but variable role in America’s welfare bureaucracy. In states like New York, Michigan, Illinois, and Florida, they account for anywhere from one-quarter to nearly one-half of all public assistance administrators. The patterns revealed in my research suggest that when black government employees reach such critical masses, compliance increases. However, many states employ relatively few African Americans. Without better training and oversight to ensure that all government workers comply with the law, these locales will continue to fall short of enacting the promise of agency based registration.

In an election marked by toxic racial rhetoric and heated debates over income equity, it’s crucial to ensure free and fair access to the ballot box, especially for people of color and folks grappling with poverty.

In an election marked by toxic racial rhetoric and heated debates over income equity, it’s crucial to ensure free and fair access to the ballot box, especially for people of color and folks grappling with poverty. Equal access does not simply mean freedom from being barred at the polls. It also implies an affirmative obligation to actively and evenhandedly incorporate Americans into the political process. Section 7 of the NVRA aimed to do precisely that, by giving low-income Americans opportunities for voter registration. That effort has been stymied by anti-democratic, racialized political maneuvering.

There are things that we can do to change this. Legal intervention against states with particularly bad track records has proven an effective strategy for spurring compliance with Section 7. Voting rights advocates concerned with oversight would also do well to remember that the state health insurance exchanges set up under the Affordable Care Act are covered by the NRVA and should be held accountable for offering voter registration services.

States can also take action to draw voters into the political process, and many are moving in that direction. But given the poor track record of the National Voter Registration Act—Section 7 especially—voting rights advocates would best not count their chickens before they hatch. As both online and automatic voter registration grow in popularity, advocates must take care to ensure that these systems work effectively for indigent Americans.

Finally, the job of expanding access to voter registration should not be left solely in the hands of fragmented state governments, particularly considering their history of non-compliance. Alternative institutions like community organizations, political groups, and social movements must be vigilant, both in challenging electoral disparities and in extending and deepening mass political engagement. In the face of intensifying racial divisions and widening partisan polarization, both state and non-state actors must work to ensure that race and poverty don’t become obstacles to a basic American right.

This article was posted in conjunction with the Scholars Strategy Network.

This essay is based on findings from, “Race, Poverty and the Redistribution of Voting Rights,” forthcoming in the June issue of the Journal of Poverty and Public Policy.

Like this article? Subscribe to The American Prospect .

Spread the word