We know that Americans are increasingly sorting themselves by political affiliation into friendships, even into neighborhoods. Something similar seems to be happening with doctors and their various specialties.

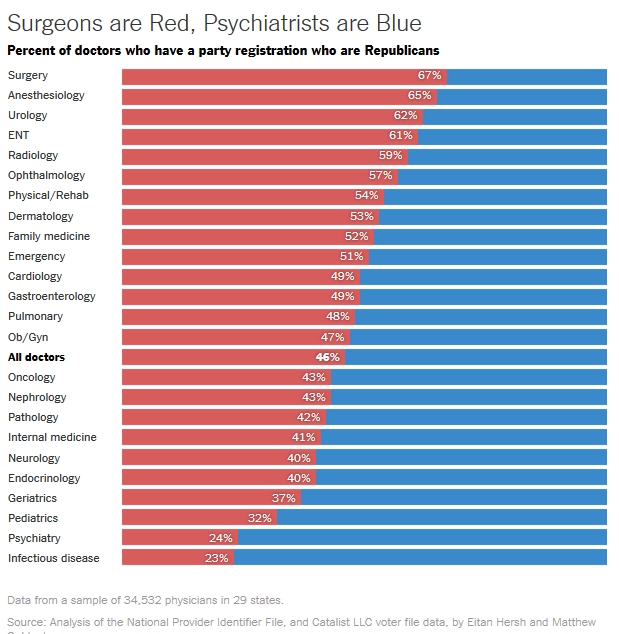

New data show that, in certain medical fields, large majorities of physicians tend to share the political leanings of their colleagues, and a study suggests ideology could affect some treatment recommendations. In surgery, anesthesiology and urology, for example, around two-thirds of doctors who have registered a political affiliation are Republicans. In infectious disease medicine, psychiatry and pediatrics, more than two-thirds are Democrats.

The conclusions are drawn from data compiled by researchers at Yale. They joined two large public data sets, one listing every doctor in the United States and another containing the party registration of every voter in 29 states.

Eitan Hersh, an assistant professor of political science, and Dr. Matthew Goldenberg, an assistant professor of psychiatry (guess his party!), shared their data with The Upshot. Using their numbers, we found that more than half of all doctors with party registration identify as Democrats. But the partisanship of physicians is not evenly distributed throughout the fields of medical practice.

The new research is the first to directly measure the political leanings of a large sample of all doctors. Earlier research — using surveys of physicians and medical students, and looking at doctors’ campaign contributions — has reached somewhat similar conclusions. What we found is that though doctors, over all, are roughly split between the parties, some specialties have developed distinct political preferences.

It’s possible that the experience of being, say, an infectious disease physician, who treats a lot of drug addicts with hepatitis C, might make a young physician more likely to align herself with Democratic candidates who support a social safety net. But it’s also possible that the differences resulted from some initial sorting by medical students as they were choosing their fields.

Dr. Ron Ackermann, the director of the institute for public health and medicine at Northwestern University, says he remembers his experience rotating through the specialties when he was in medical school. “You’ll be on a team that’s psychiatry, and a month later you’re on general surgery, and the culture is extraordinarily different,” he said. “It’s just sort of a feeling of whether you’re comfortable or not. At the end, most students have a strong feeling of where they want to gravitate.”

Dr. Ackermann, who trained as an internist, helped conduct a survey of physicians on the idea of a single-payer health care system, a liberal policy goal, in 2008. His work found similar trends of support and opposition clustering in certain specialties. (A co-author of that study is Aaron Carroll, an Indiana University medical school professor and an Upshot contributor.)

There is no way to know exactly why certain medical specialties attract Democrats or Republicans. But researchers who have studied the politics of physicians offered a few theories.

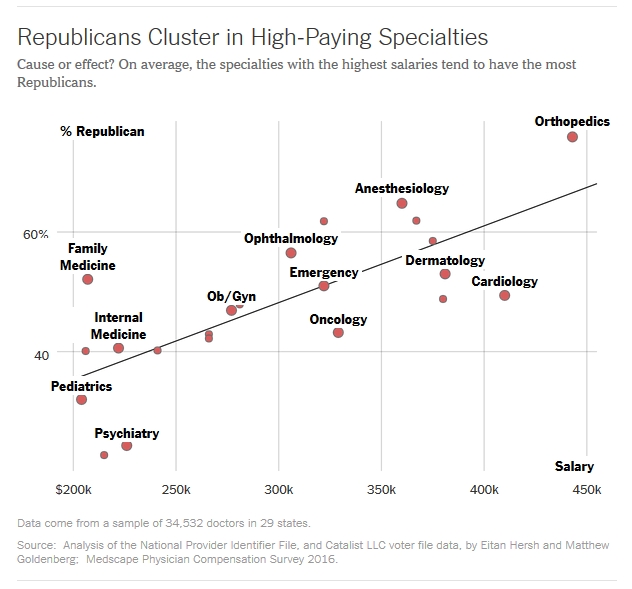

One explanation could be money. Doctors tend to earn very high salaries compared with average Americans, but the highest-paid doctors earn many times as much as those in the lower-paying specialties. The fields with higher average salaries tended to contain more doctors who were Republican, while the comparatively lower-paying fields were more popular among Democrats. That matches with national data, which show that, for people with a given level of education, richer ones are more likely to lean Republican (possibly because of a concern over the liberal policy goal of taxing the wealthiest at a higher rate).

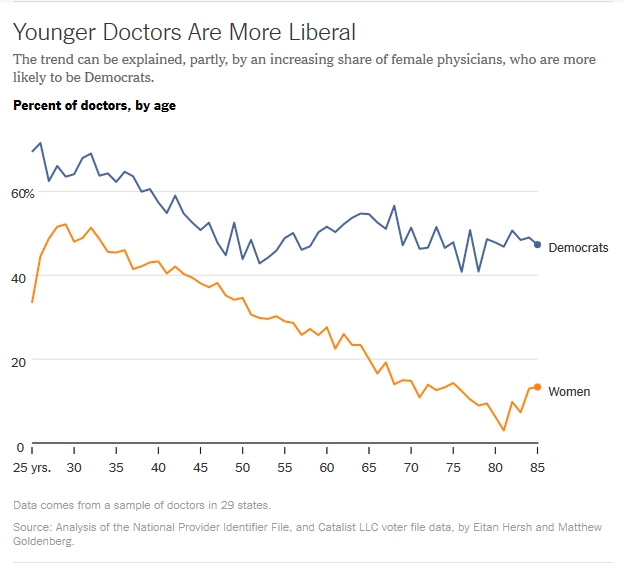

The sorting may also reflect the changing demographics of medicine. As more women have become doctors in recent years, they have tended to cluster in certain specialties more than others. The data showed that female physicians were more likely to be Democrats than their male peers, mirroring another trend in the larger American population. So as women enter fields like pediatrics, obstetrics/gynecology and psychiatry, they may be making those fields more liberal.

Over all, the partisanship of doctors looks very different from a generation ago, when most physicians identified as Republicans. The influx of women may help explain that change, too. The researchers Adam Bonica, Howard Rosenthal and David Rothman compared political donations by doctors in 1991 with those in 2011 and 2012. The study found that doctors had become substantially more likely to give to Democrats.

New doctors can’t explain all of the change, though. Even older doctors in the new data look close to evenly split between the parties. It’s likely that many older doctors have switched parties over the year. That’s true broadly for well-educated professionals in the United States, who have become increasingly Democratic in recent years.

The shift reflects how the practice of medicine has been changing, too. Doctors used to essentially be small-business owners. As such, they may have been more attracted to Republican aims of low taxes and limited regulation. These days, more and more doctors are employees of large companies or hospitals.

Should you care if your doctor is a Democrat or a Republican? Maybe. Professor Hersh and Dr. Goldenberg used their data on doctors’ partisan identification to conduct a study of primary care physicians, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences this week.

They asked the doctors to consider a group of hypothetical patients: one who smoked, one who drank, one who was overweight, and so on. They found that doctors viewed most of their patients’ health with similar seriousness and would advise similar responses. But for three of the hypothetical patients, they found differences. Those patients were devised to have health problems closely tied to hot-button political issues: One used marijuana, one owned guns, and one had a history of abortions. For those patients, Republican and Democratic doctors registered different levels of concern and said they would respond differently.

When it came to the patient with a history of abortions, doctors who were Republican said they would be more likely to encourage the patient to seek counseling and express concern about mental health consequences; they also said they would be more likely to discourage the patient from seeking future abortions. For the patient who used marijuana, Republican doctors said they’d be more likely to ask the patient to cut back and to discuss legal risks of using the drug, which is banned under federal and most state laws. For the patient with guns, doctors who were Democrats indicated they’d be more likely to tell the patient not to keep guns at home. Republican doctors, on the other hand, would be more likely to discuss safe storage options.

“These findings suggest you are going to get different care,” Professor Hersh said, adding that the differences might not matter much for the average patient. But they might for patients whose needs were closely related to politically divisive subjects, like reproductive health, with issues like contraception, abortion and prenatal screening; or H.I.V. prevention, with risk factors that include sex and intravenous drug use.

Primary care doctors and obstetrician-gynecologists, the doctors most likely to consider such issues, were among the most evenly split in the study sample. That means that patients probably can’t guess the political leanings of their doctor without asking (or checking the voter file data). The current study is only a survey, but Professor Hersh said he hopes the research spurs more examinations of how ideology shapes medical practice.

Professor Hersh and Dr. Goldenberg constructed the data set by assembling a large sample of doctors from the federal government’s National Provider Index, a file of every physician in the United States who either bills insurance or shares data digitally. There are very few doctors who are not included in this file.

They then matched each physician to data from state voter files maintained by Catalist LLC, a political data vendor. The researchers searched for doctors with matching names, living within a small geographic radius from their practice address. Not every doctor matched. Some had moved; some were not registered to vote; some had changed their names; some had common names that made it hard to make a definitive match; some lived nearby in states where the voter file does not include political information; and there may have been some mistakes in each file. But over all, the researchers were able to collect complete data for more than 55,000 physicians living in the 29 states where voter files include party registration. (Those states contain about 60 percent of the population, and are roughly, but not perfectly, representative of the country.)

For many of the measures in this article, we looked only at the percentage of “partisan” doctors, that is, doctors who recorded a political party. There was a substantial fraction of the physicians with no political affiliation, and there was a small fraction who were registered with smaller political parties. Altogether, the analysis looks at just over 36,000 doctors.

There are many more medical specialties than are included in our charts. With advice from Professor Hersh and Dr. Goldenberg, we combined many small subspecialties to form large specialties, such as “surgery.”

An earlier version of a chart with this article misstated the surname of a co-author on a study of how partisanship influences physician behavior. He is Matthew Goldenberg, not Rosenberg.

Spread the word