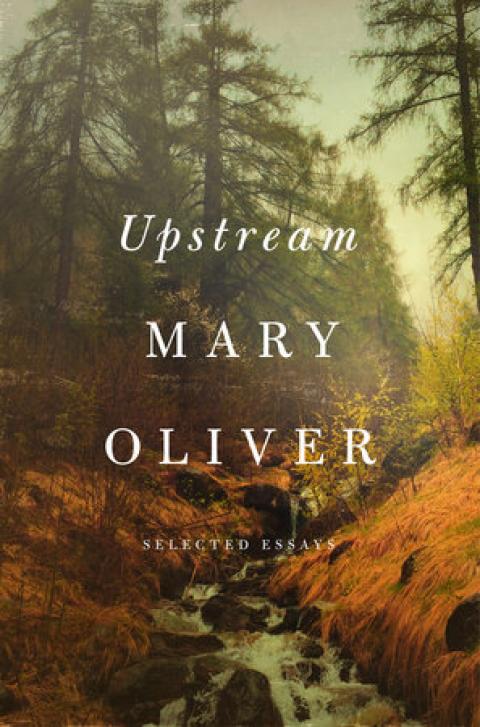

Upstream: Selected Essays

by Mary Oliver

Penguin

ISBN 9781594206702

This summer, a commercial was lauded for skewering a common bad habit. The ad, which promoted IKEA, opens on the drawing room of a lord apparently living around the time of King George III. As servants lay out a dinner of fruits, vegetables, and game birds, the bewigged gentleman calls in a painter and demands a still life on the spot. When the painting is done, footmen hustle it out of the manor and around town, showing it off to upper-class fops who flash thumbs-ups in response. They return home, triumphant, and, finally happy at his success, the man lets his poor family eat. Flash-forward to the present and footage of a dad delaying a family meal to snap pictures of the food on his cell phone. The closing tagline: “It’s a meal. Not a competition. Let’s relax.”

Indeed, let’s. In fact, we might go one better and forget the image entirely — nobody really needs their image on any screen, silver or TV or phone. No one really needs a relationship with corporate capitalism, conspicuous consumption, or cyberspace, either. All that is fungible, forgettable; it’s been replaced many times before.

What to do with the spare time left over by ceasing to engage? Consider reading Mary Oliver’s latest book, Upstream, and its meditations on inescapable, physical life and the world beyond any screen.

Mary Oliver is the country’s “far and away, the country’s best-selling poet,” according to a ten-year-old article in The New York Times. Famous for winning the 1984 Pulitzer Prize, she’s published over 30 books since 1965. Many feature famous poems or lines — and by dint of that notoriety, Oliver is easy to find in a certain kind of middle-class, left-wing American life. I’ve seen her words everywhere from Buddhist meditation sessions to Mac McClelland’s memoir Irritable Hearts (which quotes a poem about “letting the soft animal of your body love what it loves”) to the co-op where I lived in college, which bore a version of her line, “What is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?” hand-painted in a girlish curlicue over a dining room doorway.

To her vaunted curriculum vitae and relative ubiquity, Oliver, aged 81, now adds Upstream. But despite Oliver’s well-demonstrated power, one of the book’s first sentiments is a disclaimer about its smallness in comparison to the world it describes: “And whoever thinks these are worthy, breathy words I am writing down is kind… Come with me into the field of sunflowers is a better line than anything you will find here, and the sunflowers themselves far more wonderful than any words about them.”

That might be unnecessarily self-deprecating, but it’s true enough. Oliver’s power lies in words, but even more so in her power of observation. Until recently, she spent her life spent trekking through woodlands (“I walk, all day, across the heaven-verging field,” she writes) and half on the cusp of the sea, in formerly sleepy Provincetown, Massachusetts.

Despite being a thin volume, Upstream is a cognitively weighty book. It’s her rare volume of essays rather than pure poetry, although 16 of the 19 essays are reprints from earlier books. It offers no obvious order, and it sticks to no one particular subject. It is neither chronological nor purely topical, and it jumps from the natural world to famous literary lives (Walt Whitman, William Wordsworth, Edgar Allen Poe) to a beloved pet dog. It discusses the life and thoughts of Oliver’s deceased lover, Molly Malone Cook, without explaining who she is (indeed, without ever including more than an initial, M). More than a book meant to make a single point, this is a book meant to allow Mary Oliver’s vivid thoughts out into the world.

The book’s finest moments are when Oliver dwells on the nature she has spent a lifetime loving. Thankfully, these are frequent. She writes of seeing caught Bluefin tuna unloaded from fishing boats, “their bodies are as big as horses;” of the live fishes she once returned to the cold sea after unexpectedly cutting them from the body of a fish who’d just ate them (“for an instant they throbbed in place, too dazed to understand that they could swim back to life — and then they uncurled, like silver leaves, and flashed away”); of the injured bird she let slowly die in a luxurious nest of towels she’d constructed near a sliding door in her home.

Among the observations of natural beauty come slow, gentle, ponderous thoughts about the nature of love, death, and life in a changing place. Oliver avoids anything self-pitying, apocalyptic, or morbid — and in fact she doesn’t even overtly mourn her partner, whose 2005 death she grieved in the 2007 photo book Our World. Nonetheless, these philosophical musings are the point of writing. “You need empathy with it rather than just reporting,” Oliver explained to Krista Tippett of On Being in 2015. “Reporting is for field guides. And they’re great. They’re helpful. That’s what they are. But they’re not thought provokers. And they don’t go anywhere.”

This book is thought-provoking, and it does go somewhere. Where it goes is ultimately up to the reader — whose mind, after all, is the soil in which Oliver’s contemplative turns of phrase will bloom. Oliver expresses clearly that nature is our equal, if not our better, and that the nonhuman world offers a wellspring of insight to those who pay careful attention to it.

As for any IKEA commercials one might miss while out in the woods or at the shore: well, that last one went viral, I guess. But if you’ve seen it — or if you haven’t — forget it. Whatever insight it offers, remember that Mary Oliver got there first, and better, with words like these: “Writing is neither vibrant life nor docile artifact but a text that would put all its money on the hope of suggestion…Butterflies don’t write books, neither do lilies or violets. Which doesn’t mean they don’t know, in their own way, what they are. That they don’t know they are alive — that they don’t feel, that action upon which all consciousness sits, lightly or heavily. Humility is the prize of the leaf-world. Vainglory is the bane of us, the humans.”

Putting all my money on the hope of a suggestion now, I’ll say that this, and all the rest of Upstream, comes highly recommended.

M. Sophia Newman , MPH, is a journalist and a former health researcher. She has completed research on trauma at Veterans Administration hospitals in Chicago and in Bangladesh via a Fulbright grant, and has earned a certificate in global mental health via the Harvard Program on Refugee Trauma. See her writing at msophianewman.com.

Spread the word