THE ideas pioneered by the Lucas workers are just as, or more, relevant now than in the 1970s, and there are strong political similarities in the situation.

As in the ’70s, we have an economic crisis caused by unjust economic policies and the failure of successive governments’ industrial strategy.

As usual, this has hit the working class hardest, and anger over this is being channelled into racism against immigrants. Now, the environmental effects of industrial capitalism are far more evident than 40 years ago, already creating wars, militarisation and widespread concern about insecurity.

Finally, introduction of new technologies threatens structural unemployment on a scale considerably greater than the ’70s.

The Tory government’s response to the economic and political crisis, despite continuing to publicly espouse neoliberal principles, looks a lot like a classic Keynesian economic stimulus package.

In the last few months it has made decisions to move ahead with a range of industrial infrastructure megaprojects — Hinkley C, fracking, HS2 and the Heathrow third runway, as well as pressing ahead with spending £200 billion on Trident renewal.

A key element in the case for all these projects is the jobs that they will generate or preserve, although the jobs estimates are bound to be inflated, while the price tag will be massively underestimated.

Compared to the ’70s, far fewer jobs will be created in this way because, due to automation and mechanisation, they are all highly capital rather than labour-intensive.

The Lucas Aerospace workers’ idea of socially useful production suggests a far better way forward.

Even in the early phase of the environmental movement, before most socialists realised the significance of these issues, the Lucas Plan acknowledged that protecting the environment is part of the concept of socially useful production.

With the exception of HS2, all the new projects are environmental anathema, and the damage that project would do to the English countryside and people’s homes and communities, for the sake of saving 30 minutes of executives’ time, makes it emblematic of neoliberalism.

The working-class people who voted for Brexit are demanding jobs and regeneration of their communities, but these industrial vanity projects are not the solution.

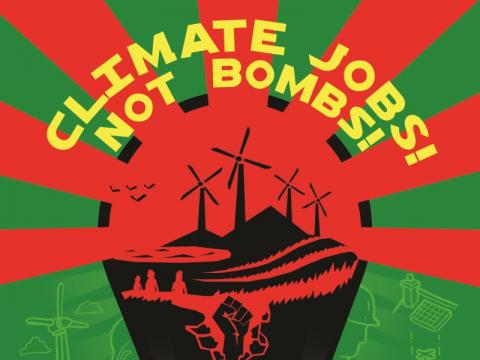

Now is the moment to realise the proposals of the Campaign Against Climate Change Trade Union Group (Million Climate Jobs Campaign), which is often seen as a successor to the Lucas Plan.

We should be investing in renewable energy, home insulation, public transport etc as part of the international trade union initiative of Just Transition, ie transition to a low-carbon economy with job protection for workers in industries that need to be phased out.

Imagine what could be achieved in regional economic renewal and environmental benefits with the Trident billions.

But exactly how that money should be spent should not be decided by economic planners alone.

One of the great strengths of the Lucas Plan was that it came from the bottom up, from workers, not managers.

Recognising that they could not, by themselves, define what people need, the Lucas workers began to work with various regional communities to develop “popular planning for social need.”

In London, the Greater London Council created technology development networks that involved users, for example disabled people, in technology design.

These traditions of bottom-up local planning have been continued by various citizens’ local planning initiatives, such as Just Space in London, and would be vital to a democratic solution to the crises.

The current economic and environmental crises are symptoms of a deeper crisis in the industrial capitalist mode of production, and they demand a fundamental rethink of how we produce the basic things that people need for a decent life.

One of the less well-remembered, but crucial aspects of the Lucas Plan was the workers’ struggle against the automation and deskilling of their work with computer-controlled machinery, a struggle shared with trade unionists around the world in that period.

As Phil Asquith of the Lucas Combine puts it, “Harold Wilson’s ‘white heat of the technological revolution’ was burning up workers’ jobs.’

The continuation of this trend over the last 40 years is a major source of the jobless recoveries and income polarisation that are creating the “squeezed middle” of angry, Daily Mail-reading, Brexit voters.

Forecasts suggest that digital technology will eliminate half the jobs in the economy over the next 20 years, but its track record shows that it creates far fewer new jobs to replace them.

One response to this that has become popular on the left is the belief that automation will usher in a post-capitalist society, if we can only feed those useless human workers with basic income.

This is a complex argument, but one thing for sure is that this was not the Lucas workers’ philosophy.

Instead of: “Demand Full Automation, Demand Universal Basic Income, Demand the Future,” they would have reminded us that the romance of high-technology leads to what historian of technology David Noble aptly called: “Progress without people.”

The Lucas workers’ slogan would likely have been: “Demand Democratic Control of Technology, Demand Socially Useful Production, Demand Equality and Sustainability.”

They were very clear that the idea of socially useful production is also about how things are produced.

There is no point in socially useful products if they are made in a way that alienates and deskills the workers who produce them.

They went on to design “human-centred technologies,” in which the point was to use and develop workers’ skills, rather than design them out of the production process.

A skills and people-based, more labour-intensive approach is, in the era of Brexit and environmental crisis, a much better way to create a socially just, sustainable economy than old-fashioned, capital-intensive high-tech mega projects. This is the agenda we will be discussing in Birmingham today.

Spread the word