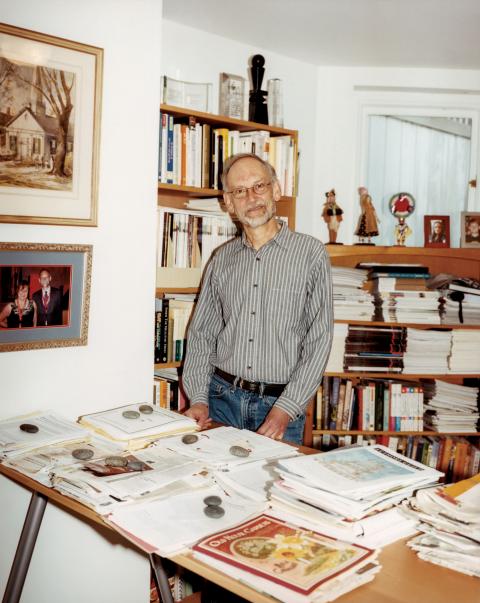

The first time I had dinner with Harold McGee, he didn’t touch the food. McGee is the bookish 65-year-old author of On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen, first published in 1984, last revised in 2004, and so dense with gripping material like the denaturing effect of heat on meat proteins that it cannot possibly have been read cover to cover by more than two or three people, McGee included. On Food and Cooking is also a perennial bestseller with hundreds of thousands of copies in print — a bible for home cooks and chefs all over the world and the primary reason that McGee has become the great secret celebrity of the contemporary food scene.

I knew for years that McGee lived in my San Francisco neighborhood, and I had been fantasizing about dinner with him ever since the night I tried to make mayonnaise by putting an egg yolk and a teaspoon of water in a bowl and whisking in half a cup of extra-virgin olive oil. This mixture deteriorated into such a disgusting pool of grease that I threw it out. I cracked a second egg, separated the yolk, added more water, and tried whisking in another half cup of olive oil. Heartbreak again, this time coupled with self-doubt.

I repeated this process five times, ever more certain that something was wrong with me, until I had gone through ten dollars’ worth of oil and all but one of my eggs with only minutes before my dinner guests were due. I owned On Food and Cooking, having bought it long before in the hope of making myself into a superior cook, but I had given up on reading it after repeated runs at Chapter 1: “Milk and Dairy Products.”

The mayo mess broke my OFAC impasse. Frantic, I scanned the index, found my subject between matzo and mead, and read McGee’s primer on emulsified sauces, of which mayonnaise is one. I felt calmed by McGee’s explanation that the essence of an emulsion is the dispersal of oil into a zillion tiny droplets suspended in water, aided by an emulsifier in egg yolks known as lecithin. I felt reassured by the news that fancy olive oil is notoriously temperamental in mayonnaise, and I nearly wept with relief at the sight of a section titled, “Rescuing a Separated Sauce.” Following McGee’s directions, I put a few tablespoons of water in a cup and then, whisking vigorously, slowly drizzled in my final batch of yolk-speckled oil. Moments later, I emerged as the man I am today, capable of making mayonnaise with confidence.

I promptly bought McGee’s second and third books, The Curious Cook: More Kitchen Science and Lore (1990) and Keys to Good Cooking: A Guide to Making the Best of Foods and Recipes (2010). I soon experienced similar triumphs — like making french fries that did not fall limp within minutes of leaving my deep-fryer. I came to think of McGee as an imaginary friend who lived in my kitchen, knew everything, and was happy to share.

I offer this story because it is the quintessential McGee story: OFAC purchase with intent to self-educate; failure of will; years of ignoring book on shelf; culinary crisis leading to Hail Mary reference; success; love. The story is also quintessentially modern, speaking to the widespread belief that data and the scientific method can make us all happier, slimmer, fitter, and better in bed. Results are decidedly mixed — if not terrible — in most of these areas, but cooking’s variables are more knowable and controllable. Cooking involves near-daily experimentation with chemistry (baking soda), physics (heat), and biology (kombucha). Its methods are mostly traditional, too, resulting from a thousand years of unscientific trial and error and therefore rife with easy targets of the kind identified and shot down by McGee in a 1985 article for The New York Times about the time-worn notion that searing meat seals in juices, which turns out to be nonsense.

The language of science, meanwhile, has replaced French classicism as the lingua franca of the culinary world. Major culinary schools offer a food-science major with OFAC on their reading lists, TV shows like Alton Brown’s Good Eats have enshrined the scientific method as the secret to kitchen success, and bestselling books like J. Kenji López-Alt’s The Food Lab: Better Home Cooking Through Science describe elaborate experiments proving that burger patties smashed flat on a griddle do not, in fact, turn into hockey pucks. We are living, in other words, through a period of what you might call Peak McGee.

BACK TO THAT first dinner. McGee is working on a new book that he describes somewhat cryptically as “a guide to the smells of the world,” and he fiercely guards his writing time. So I didn’t actually ask him to dinner. I asked if he might consider meeting me for conversation, maybe at a restaurant. The chefs of every fine-dining eatery in San Francisco would have recognized and welcomed him, but he insisted on a modest French bistro called Le Zinc near his home in the Noe Valley neighborhood. McGee apparently likes to take a walk after his writing day.

I arrived at 5:30 p.m. on a Tuesday and found Le Zinc empty except for the maitre d’ and McGee: long-limbed and slender almost to the point of delicacy, with a neatly trimmed beard, gold wire-rimmed spectacles, and a social awkwardness obvious from ten paces. McGee sat at a little round table in back and was drinking white wine. I joined him and, hoping to lure him toward a meal, ordered steak tartare to share.

While we waited for the food, I asked how McGee came to write OFAC. Sitting up straight in his chair and speaking in a genteel and controlled manner, McGee began: “I grew up mainly in the Chicago area. My mother was a housewife, and my father worked at the Sears mother ship downtown.” A chemical and electrical engineer, his father met McGee’s mother during a postwar stint in India. The family lived in what were then newly built suburbs, where McGee spent nights in the backyard with a ham radio, communicating with people on the far side of the Earth.

Our waiter set down a white plate with a red cylinder of raw chopped beef surrounded by green salad and toast. McGee ignored it and said that he went to the California Institute of Technology to study astronomy but, after one year, “realized that I had friends who could look at a question on our homework, look at the sky for a minute, write an answer, and then go to the beach. And I would sit there and sweat even when things were explained to me.” McGee also discovered a love of literature “to the point where I was like, ‘Maybe I’m in the wrong place and should transfer to a liberal arts school.’”

An English professor convinced McGee to stick around and study the Big Bang and Romantic poetry side by side. McGee described this as a remarkably happy period followed by equally enjoyable years in the Ph.D. program in English literature at Yale, studying under Harold Bloom. McGee’s college girlfriend, Sharon Long, joined him at Yale, first as an instructor in the biology department, where she gave a lecture on the thermodynamics of fudge making. Later she became a doctoral student in biochemistry and genetics.

McGee said that he finished his dissertation on John Keats in 1977 and began an unsuccessful three-year search for a tenure-track position. McGee was getting to the part of the story where he struck on the idea for OFAC, and I could feel his tone change to emphasize doubt and happenstance more than genius or vision. “We had friends in biology and literature, and we would get together on weekends for a potluck,” McGee said. “Often, what we had in common to talk about was food. You spill wine and someone says, ‘Put salt on it,’ and someone else says, ‘Why?’ Then the chemists start to speculate.”

McGee said that he finally gave up on his dream of becoming a professor — a painful passage — and looked around for a writing project, perhaps a book on some aspect of science. At one of those potlucks, a friend confessed that he loved beans but suffered terribly when he ate too many.

“He wanted to know if there was such a thing as a ‘Fart Chart’ of different kinds of beans,” McGee said. “And if he used a different kind of beans, could he maybe eat a couple more servings? He also wondered if there was something he could do to the beans ahead of time.”

The next day, McGee went looking for answers. At the Yale biology library, he discovered that plenty of food-science research had been published by and for the food manufacturing and packaging industries, but little of it had been shared with chefs or home cooks.

“I spent hours in that library because I had never seen anything like it,” McGee told me. “Poultry science and agricultural and food chemistry. I would just flip through random volumes and see microscopic studies of things I eat every day. It seemed so cool and unexpected. It took more than a day to home in on the right sources about beans, but not only did I find out what’s in them and what you can do about it, but there is a fart chart and there are things you can do to lessen your suffering. Most of the research in the field of flatulence was funded by NASA. If you think about it, it makes good sense — these were still the days of capsules.”

McGee quit his last Yale teaching job to write a book proposal. “Fear, shame … I had a terrible time around then with panic attacks,” he said. “They just set in. A colleague of mine who got a professorship at Wellesley, his wife was a clinical psychologist. So I was able to confide in them. You know, ‘You’re not about to die …’” McGee laughed. Richard Drake, a Yale friend who also failed to land a tenure-track job, described this period as “a very rough time for Hal. What is he going to do for a career?”

At about the same time, Long was out at dinner when she mentioned McGee’s book idea to a man who happened to know a scout for Scribner’s publishing house. Not long after, “I get a letter out of nowhere saying Mr. Scribner is coming through New England, and could I find time to have lunch with him?” The two met and, after they ate, Scribner said, “I want to publish your book. What do you need?” McGee asked for and received a $12,000 advance.

McGee had recently moved to Boston to live with Long, who had a postdoctoral fellowship at Harvard. He soon discovered Radcliffe’s Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America and its immense collection of food books. “I could walk into a room lined with books arranged chronologically, so when I was writing about meat, I could start with the Greeks and work my way forward.” The longer McGee worked, the more certain he became that he was onto something special. “The excitement of pulling things together that I knew belonged together that no one had put together before,” he said. “I was always looking over my shoulder, convinced that someone was going to scoop me by a year.”

THE SECOND TIME I had dinner with Harold McGee, once again at 5:30 p.m. at an empty Le Zinc, I asked him if he would consider sharing some food.

McGee nodded, so I ordered steak tartare again, foie gras with brioche, and niçoise salad. This time, when the tartare arrived, McGee began to eat.

I said, “Is steak tartare really safe?”

“It isn’t always,” McGee replied. “You have to trust. You had it last time, and I did not.”

“You were waiting to see if I died.”

McGee smiled and told me that his father loved rare hamburgers. Near the end of his life, this predilection worried McGee enough that he developed a method of preparing safe rare hamburgers at home based on the insight that harmful bacteria live only on the surface of muscle tissue: He bought beef chuck in large intact pieces, immersed them briefly in boiling water, then ground them shortly before cooking.

Our foie gras arrived, and, while we ate, I asked to hear the life story of OFAC — how it transformed McGee from failed academic to his current role in the culinary world. It took a while to air out all the false starts, setbacks, and lucky breaks. McGee began by saying that, before he even finished OFAC, Long was offered a professorship at Stanford.

On their drive west in 1980, the couple stopped in New York so that McGee could hand-deliver his manuscript at the Scribner building on Fifth Avenue. The book languished for four years. A young editor took over the project and cut out everything that Charles Scribner Jr. asked McGee to include — history, anecdote. McGee threatened to return his advance and take the project elsewhere and was then invited back to New York, where he spent days in a windowless room restoring the book.

When OFAC came out, reviewers ignored it, and the book sold poorly. “You have to remember there was no Starbucks, no balsamic vinegar. Nobody cooked with olive oil except horrible cheap stuff,” McGee said. “It was a completely different world.” American professional chefs, furthermore, saw food science as the province of industrial food manufacturing. McGee got a break in 1985, when the food writer Mimi Sheraton reviewed OFAC for Time and called it “by all odds a minor masterpiece.” Sales picked up, McGee signed with an agent, and he received a modest advance to write The Curious Cook around a series of home-kitchen experiments — but it was still not an easy period.

McGee was the primary parent of his and Long’s two children, filling his free time by cooking for his family — he had a big pizza phase — and writing articles like “Matching Pots and Pans to Your Cooking Needs” for Science Year 1987, a supplement to the World Book Encyclopedia. “Colleagues of my wife’s would try to make connections for me at Stanford, so that I could be an instructor or something,” he told me, “and they all went uniformly nowhere. People had a ‘Who do you think you are?’ attitude, like I was just a hanger-on looking for a handout, which did nothing for my confidence in what I was doing with my life.”

In 1992, the year Long won a MacArthur “genius” grant for molecular biology, McGee helped organize a small cooking-science conference in the Sicilian village of Erice. The venue liked events to have serious-sounding names, and The Science of Cooking didn’t cut it. “Molecular biology was chic at the time,” McGee told me, “so we settled on The First International Workshop on Molecular and Physical Gastronomy.”

Throughout the late 1990s, as McGee prepared a second edition of OFAC, public interest in the topic began to grow. Robert Wolke launched a cooking-science column for The Washington Post at the same time that Alton Brown’s Good Eats debuted on the Food Network. But the biggest change in McGee’s fortunes came from his friendship with a young English chef named Heston Blumenthal.

Years earlier, before Blumenthal had a restaurant of his own, he systematically worked his way through the French classical tradition at home — “while all my friends were going out and having pints, a kebab, and a fight,” as he put it. Reading McGee, Blumenthal said, transformed the way he looked at food. The revelation about searing meat not sealing in juices “was a life-changing moment, because it questioned one of the most biblical laws in cooking.” Blumenthal eventually opened The Fat Duck outside London, which became by far the most famous restaurant in the U.K.

McGee, taking his last sip of wine, recalled receiving a note from Blumenthal asking if he would serve as a consultant. “I think he replied to me over email,” Blumenthal said, “but I never read it as I was computer illiterate at the time.” Blumenthal began to produce dishes like sardine-on-toast sorbet and edible spheres of vodka and green tea dropped into liquid nitrogen. He soon gained recognition as a leading practitioner of a wildly experimental — and science-driven — new cuisine that was also taking root in Spain, erroneously called molecular gastronomy out of the mistaken notion that it emerged from those Erice workshops.

Blumenthal and McGee finally met in the Milan airport en route to Erice, where they were both scheduled to attend the 2001 Workshop on Molecular Gastronomy. “I was completely thrown off by the chance encounter,” Blumenthal said. “My mind was running through the endless experimentation with food that his book had inspired, so I blurted out the first thing that came to mind: ‘It’s all your fault!’ I think he was a little taken back.”

The two began having long phone conversations, like the one on Christmas Day 2004 when McGee, who had just published the second edition of OFAC, said something like, “I need to catch up on the world.” Blumenthal invited him to Europe for an eating tour. The next August, after The Fat Duck claimed the top spot on Restaurant magazine’s list of the World’s 50 Best Restaurants, the two dined at El Bullí in Spain, where they met Ferran Adrià, who famously closed his dining room for six months a year to work with scientists on the development of new dishes.

The following summer, Blumenthal and McGee returned to Spain to stay on the yacht of Microsoft billionaire and cooking obsessive Nathan Myhrvold. They got to talking about the widespread misunderstanding of what they preferred to call “modernist cuisine.” So few people could afford to eat in restaurants like The Fat Duck and El Bullí, and their more dramatic dishes were so easily sensationalized, that the entire movement was at risk of looking like a novelty act aided by laboratory equipment.

“We wanted to write a statement on the new cooking to give some clarity,” said Blumenthal. Together with Myhrvold, he and McGee dined yet again at El Bullí, discussed the issue for hours with Adrià, and then returned to Myhrvold’s yacht. “We’d spend a couple hours at a time, talking it over and writing drafts,” McGee recalled. “Then we’d go have fun and come back and have arguments about how it should be released.”

The result, published by The Guardian in December 2006, was titled “Statement on the ‘New Cookery.’” Co-authored by Blumenthal, Adrià, Thomas Keller of The French Laundry, and McGee, it rejected the term “molecular gastronomy” and, among other things, declared that “the disciplines of food chemistry and food technology are valuable sources of information and ideas for all cooks. Even the most straightforward traditional preparation can be strengthened by an understanding of its ingredients and methods.” In effect, the three most famous chefs in the Western world officially joined the author of the definitive work on the subject to send every serious cook scrambling to learn a little kitchen science.

“That statement was important for a while,” said McGee. In Blumenthal’s view, it still is. Modernist cuisine was arguably the most significant transformation in global culinary culture in a century or more, and, he said, “My conversations with Harold were the seeds that led to the modernist movement.”

THE THIRD TIME I had dinner with McGee, I wanted to know what it would be like to dine with so much wonderful information about food in your head. I knew that experimental cuisine was not where McGee’s heart lay — his intellectual and gustatory compass points more toward the humanistic true north of simple pleasures. His own cooking has always been modest, and his home kitchen is not cluttered with fancy equipment. So I chose another classic French bistro, called Monsieur Benjamin, run by Corey Lee. I picked McGee up one evening at the Victorian home he shares with Elli Sekine, a food and travel writer (he and Long separated in 2003).

Chef Lee, I knew, had found OFAC early in his career and was one of the many chefs who emailed McGee for advice — in Lee’s case, on a plan to air-cure foie gras. In 2007, The New York Times asked McGee to write a column titled “The Curious Cook,” and he began receiving an endless stream of queries. Daniel Humm of New York’s Eleven Madison Park sought insight on why the combination of quince and gelatin caused stock to become cloudy. Thomas Keller invited McGee to give a talk to the staff at The French Laundry and asked his help in identifying the best way to preserve the bright-green color of vegetables during cooking. He still spends time answering questions from culinary students, too, and cooking-school instructors, and home cooks (“Good Afternoon Harold, I am trying to lighten up my grandma’s carrot cake recipe …”).

McGee is now a regular at culinary and food-science conferences, and he recently did a series of short videos for Anthony Bourdain’s Mind of a Chef, floating over an animated background as the official nerdy professor of contemporary food television. Each fall, he travels east for Harvard’s Science and Cooking course to give the keynote lecture. The class came about because of a collaboration among mathematician Michael Brenner, physicist David Weitz, and Ferran Adrià. As they developed the syllabus, Brenner said, “There was no question that On Food and Cooking was the best thing ever written on the subject. Harold is the leading food intellectual of our time.” When the course debuted in 2010, more than 700 Harvard undergraduates signed up for 300 spots. It has now become the new “physics for poets,” the standard gut-science course for nonmajors. The online edX version has drawn nearly 200,000 subscribers.

McGee is no longer the only player in the field. Myhrvold’s six-volume opus, Modernist Cuisine, self-published in 2011 at a cost of more than a million dollars and currently retailing for $625, is an obsessively exhaustive encyclopedia of the science behind experimental cooking. Newer titles include The Science of Good Cooking by the editors of America’s Test Kitchen and Cooking for Geeks: Real Science, Great Cooks, and Good Food. But all these writers acknowledge McGee. “He taught us that most of the stories we had been told about food were just that, clever stories,” said Myhrvold.

The maitre d’ at Monsieur Benjamin recognized McGee and led us through the well-heeled crowd to an excellent table in back, where I ordered oysters and sea urchin, aged serrano ham, melted Époisses cheese with toast, cold beef tongue, chicken consommé, blanquette de veau, and quail à la chasseur.

McGee seemed delighted to be there, and he gamely offered that urchin tastes the way it does because of the bromine and iodine in seawater. He tasted the ham and told me that pork legs can be thought of as machines for moving pigs, complete with small enzymatic machinery for dismantling worn-out old cells and building new ones. Beef tongue provoked a disquisition on the fact that its muscles have to move in complicated ways and are not supported by bone — like, for example, biceps. “The tongue is a really unusual free agent that has to do whatever it does independent of the rest of the body,” McGee said.

Then our waiter set down a beautiful plate of charcuterie that I had not ordered. I suspected that it was a gift to McGee from Chef Lee, who had once told me that he owned OFAC for years without using it. Lee finally met McGee at The French Laundry, where Lee trained under Keller. “I remember expecting to talk to a scientist,” Lee said, “and realizing I’m actually talking to someone who has great appreciation for cuisine and deliciousness.”

Watching McGee now, I saw what Lee meant: Behind the erudition, those gentle eyes closed with every bite, savoring flavor and texture. I noticed something else, too — not just modesty but lack of ego. McGee was not like a great novelist or musician who set out to make his mark on the world. He was curious and listened to his authentic interests and never stopped trying to be useful. In an industry dominated by big personalities competing for attention, chefs can’t help but love McGee’s combined dedication to service and lack of interest in the spotlight.

“Very clean and fresh,” he said suddenly, after swallowing an oyster. “Fresh like a cold ocean, not a lukewarm one.” Perhaps thinking of his new book, McGee said, “When I taste that, I think of two different things, cucumbers and blue borage flowers. It turns out that among the aroma molecules we’re tasting, several occur in both plants, and that’s why you can use borage as a garnish to give the hint of the ocean when there’s no seafood in a dish.” McGee then picked up another half-shell, slipped the oyster into his mouth, and closed his eyes.

DANIEL DUANE won a National Magazine Award in 2012 for a story about cooking with Thomas Keller. His work appears regularly in The New York Times, Food & Wine, and Men’s Journal.

CARLOS CHAVARRÍA is a photographer from Madrid living and working in San Francisco.

Spread the word