Under orders from President Donald Trump, the Army Corps of Engineers on February 7 approved a final easement allowing Energy Transfer Partners to drill under the Missouri River near the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota. Construction has restarted, and lawyers for the company say it could take as little as 30 days for oil to flow through the Dakota Access pipeline.

While the Standing Rock Sioux and neighboring tribes attempt to halt the project in court, other opponents of the pipeline have launched what they’re calling a “last stand,” holding protests and disruptive actions across the U.S. In North Dakota, where it all began, a few hundred people continue to live at camps on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, using them as bases for prayer and for direct actions to block construction. Last week, camps were served eviction notices from Gov. Doug Burgum and from the Bureau of Indian Affairs, demanding that they clear the biggest camp, Oceti Sakowin, by Wednesday and a smaller camp, Sacred Stone, within 10 days.

The fight against DAPL didn’t come from nowhere. It’s a direct descendant of the Keystone XL fight — both pass through the territory of the Oceti Sakowin, or Seven Council Fires, which includes bands of the Lakota, Nakota, and Dakota people. And when Standing Rock tribal members saw that it was time to mobilize, they turned to relatives that had fought the Keystone XL.

In 2014, Joye Braun was living at an anti-Keystone XL camp called Pte Ospaye, on the Cheyenne River reservation, when she first heard about a new pipeline that would pass just outside the border of the Standing Rock reservation, on land leaders say would be tribally controlled if the U.S. government obeyed its treaties. “I went holy crap, here comes another one,” she said. Two years later, she would find herself helping set up Sacred Stone camp, the first anti-Dakota Access pipeline camp.

Now, most of the thousands of people that visited Standing Rock last fall have returned home, and some have taken up long-shot local fights against the oil and gas industry. In Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Tennessee it’s the Diamond pipeline; in Louisiana, the Bayou Bridge. In Wisconsin, the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa actually voted to decommission and remove the Enbridge Line 5 pipeline from their reservation.

Many communities have turned to direct action as a last resort. The city of Lafayette, Colorado, which has long attempted to block fracking in the area, has even proposed a climate bill of rights, enforceable via nonviolent direct action if the legal system fails.

In at least four states, encampments built as bases for pipeline resistance have emerged. They face corporations emboldened by Trump and the Republican-controlled Congress, which have used their first weeks in power to grant fossil fuel industry wishes, overturning environmental protections, appointing Exxon Mobil CEO Rex Tillerson as secretary of state, and reviving the halted Dakota Access and Keystone XL pipeline projects.

“Forces arrayed against us are quite wide in my opinion,” said Owl, a member of the Ramapough-Lunaape tribe who helped set up a camp in New Jersey to oppose the Pilgrim pipeline. “They are hell-bent on this infrastructure.”

The Trans-Pecos Pipeline

Nearly all of Texas is webbed with oil and gas pipelines, except for the virtually industry-free Big Bend region, known for its night skies devoid of light pollution. There, another pipeline last stand is underway.

Former President Barack Obama’s administration quietly approved the Trans-Pecos pipeline’s border crossing last May. It is now 96 percent in the ground, set to be complete in March. The 42-inch pipeline would transport 1.4 billion cubic feet per day of natural gas obtained via hydraulic fracturing from the state’s Permian shale basin. It would travel along 148 miles before continuing into Mexico. Although it was commissioned by the Mexican government’s Comisión Federal de Electricidad, the line will have a few taps between the U.S. and Mexico, and has been permitted as a domestic project that benefits the public. This means it gets common carrier status, allowing the company to acquire access to private property via eminent domain, despite landowners’ objections.

With guidance from local indigenous leaders, Frankie Orona and Lori Glover have been helping run a camp called Two Rivers on Glover’s land near the route since January, regularly carrying out direct actions to stop construction. The camp hosts around 10 people during the week, ballooning at times to between 50 or 100 on weekends. Still, the resistance operates on a much smaller scale than Standing Rock. “We don’t have the numbers to do the same kind of direct action, because can wipe us out in one day, and we’re pretty much done,” Orona said.

A second camp called Camp Toyahvale opened soon after Two Rivers in objection to plans by Apache Corporation to use hydraulic fracturing to access newly discovered oil and gas. For now, it is dedicated to education rather than direct action.

For years, the idea of stopping the Trans-Pecos pipeline seemed to be a lost cause, said Glover, who has been trying since 2014. She and others oppose the pipeline because it boosts the economic sustainability of fracking operations and opens the door to further industrialization of the remote area. But neighbors once fired up over the project had begun to let it go. “All the money that was spent, all the meetings — just wasted, just worth nothing,” she said, and the pipeline permitting agency “did not give it a second thought.”

But then Orona, head of a group called Society of Native Nations, was called to North Dakota last August by fellow members of the American Indian Movement to fight the Dakota Access pipeline. When he returned, he began protesting at the headquarters of Energy Transfer Partners, which is also in charge of the Trans-Pecos pipeline. He met Glover there.

“I thought, that doesn’t look good for us,” Orona said, “if we’re working on this pipeline in North Dakota, but we’re not working in our own backyard.

Atlantic Sunrise Pipeline

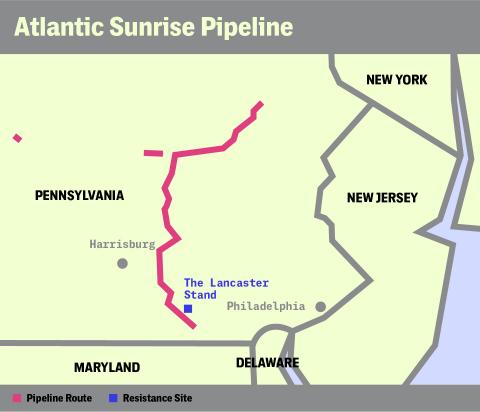

Less than a week before the Army Corps announced it would approve an easement for the Dakota Access pipeline, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which permits interstate natural gas pipelines, gave the okay for the pipeline operator Williams to begin constructing the Atlantic Sunrise pipeline in Pennsylvania. It awaits an Army Corps permit. The 42-inch pipeline is an extension of largest volume natural gas pipeline in the U.S., the Transco line. Part of the point of the Atlantic Sunrise project is to allow the Transco to switch directions, carrying gas from Pennsylvania’s Marcellus shale region, a center of the U.S. fracking boom, to markets in the south, rather than from south to north as it has run historically. The 183 miles of new Atlantic Sunrise pipeline will increase the system’s capacity by 1.7 billion cubic feet of natural gas per day, some of it destined for export.

The line will cross 388 water bodies and 263 acres of forest. Last week, in comments submitted to FERC, the Environmental Protection Agency questioned the rushed permitting process. One of FERC’s commissioners resigned as Trump took office, leaving the agency unable to approve any new projects. The Atlantic Sunrise was okayed on his very last day.

Landowners have argued that the extension is being constructed for the benefit of a private corporation and is not a public good that merits the taking of private property via eminent domain. The Clean Air Council has pointed to energy analyst predictions that say the area is being overbuilt with pipelines and that markets ultimately will not support the extraction of enough gas to fill the expanding network that includes the Atlantic Sunrise.

With FERC’s announcement, the fight for communities opposed to the project enters a new phase. Lancaster Against Pipelines announced the opening of an encampment that will serve as a base for nonviolent direct actions. Until the final permits are decided, the camp organizers are focused on preparing the site for campers, and are active mostly on weekends.

Mark Clatterbuck, one of the camp’s organizers, and his daughter Alena traveled from Pennsylvania to visit Standing Rock over Labor Day weekend. Alena joined the prayer group that, in an incident now infamous, unexpectedly encountered construction at a site that had, only one day before, been identified by the tribe as burial grounds. Video footage of security guards using biting German shepherds to fend off the nonviolent group galvanized people across the U.S. to go to Standing Rock.

The Clatterbuck family and some of their neighbors had been fighting the Atlantic Sunrise pipeline since 2014. Standing Rock provided a jolt for the group. They had been considering building tree stands along the planned route, “Then North Dakota happened,” Mark’s wife Malinda Harnish Clatterbuck said, and the group began drawing up plans to camp.

Sabal Trail Pipeline

Last August, on the same day that Standing Rock Sioux tribal chairman Dave Archambault was arrested in one of the first direct actions to block construction of the Dakota Access pipeline, the Army Corps of Engineers granted the final federal permits needed to construct another pipeline, the Sabal Trail. The 36-inch pipeline, owned by Spectra Energy Partners, NextEra Energy, and Duke Energy, would carry more than a billion cubic feet per day of natural gas along 515 miles from Alabama, through Georgia, to Central Florida. It’s set to begin operating at the end of June, and according to the company would fuel natural gas plants. Export terminals have been proposed near the pipeline’s endpoint.

Back in 2014 Ted Turner was already petitioning for an alternative route, worried that his Georgia plantation, where he hunts quail, sat too close to a compressor station that would worsen air quality. Meanwhile, at the opposite end of the economic spectrum, most of the project passes through places whose low income and racial or ethnic composition qualify them as environmental justice communities.

The Environmental Protection Agency has raised issues as well, sending a letter to the permitting agency FERC in 2015, noting, “The EPA has consistently expressed concerns over the preferred route.” It added, “The EPA is requesting that the FERC develop an alternative route to avoid impacts to the Floridan Aquifer and its sensitive and vulnerable karst terrain.” Karst is a geological formation made up of limestone or other soluble materials, marked by sinkholes and caverns.

A month later, the EPA abruptly changed its position, filing another letter stating that the agency had received new information and now believed that “the Applicants fully considered avoidance and minimization of impacts during the development of the preferred route.”

The Sierra Club, Flint Riverkeeper, and Chattahoochee Riverkeeper are in the midst of a lawsuit over the construction, arguing in part that FERC did not consider the climate impacts of the pipeline. Meanwhile, construction is underway, and many have turned to direct action.

A network of encampments and planning hubs have sprung up since last fall, run by a range of organizers with various missions. The two biggest camps held 40 to 50 people total the week prior to Trump’s inauguration, but since then they’ve both stopped inviting overnight campers and transformed into an educational center and a meeting house for planning actions. Visitors to the Crystal Water camp are trained to recognize construction violations.

Four small camps in the Goethe State Forest, called the Heartland camps, are jumping off points for direct action. Visitors are advised to reach out to organizers before coming. “This is not the Standing Rock experience most think they are coming to see. Many people have come and not been prepared for the realities of primitive camping.” said Christine DeVore Santilo, adding that a few days is the most anyone has stayed.

According to Panagioti Tsolkas, who’s been involved in fighting the project for years, Standing Rock shaped the last six months. “It’s a different context in many ways, but the inspiration that’s come from organizing in indigenous communities is a lot of what’s sparked what’s happening now.”

Pilgrim Pipeline

Along one of the busiest traffic corridors in the northeast, New York’s thruway, the Pilgrim Pipeline Holdings is considering building a parallel duo of pipelines that would move 178 miles between New York and New Jersey. In one pipe, 200,000 barrels of crude per day, obtained from North Dakota’s Bakken shale formation via hydraulic fracturing, would run south to refineries and marine terminals in Linden, New Jersey, and from there its sister pipe would send 200,000 barrels per day of petroleum products north toward Albany, New York.

The company has not submitted a full application to New York or New Jersey, and this preferred route is not yet the chosen route. According to a draft environmental impact statement from September 2016, the potential route would pass through the Ramapo river basin aquifer system, and over two aqueducts that supply New York City, the Catskill Aqueduct and the Delaware Aqueduct. The company argues that the pipeline is a safer alternative to crude traveling via barges on the Hudson River or by trains.

The line would also pass through the Ramapo Mountains. “All the major infrastructure comes through Ramapo Pass – these mountains we took refuge in when we had the genocide against native people,” said Owl, a member of the Ramapough-Lunaape tribe. Owl’s people are descendants of the Munsee band of the Lenape tribe, whose members were largely forced by white settlers to migrate in the 1700s to Canada and other places.

After a visit to Standing Rock last fall, Owl helped his tribe found a camp, called Split Rock Sweetwater, in protest of the Pilgrim pipeline. No one is living at the camp permanently, but there’s always someone on site available to explain its purpose to visitors.

“The original decision was in solidarity with Standing Rock. We realized they’re not just fighting for water there but for all of our waters,” he said. When he visited North Dakota, Owl presented Standing Rock tribal leaders with a Ramapough-Lunaape resolution banning fossil fuel infrastructure from passing through their traditional territory.

The Ramapough-Lunaapes are perhaps most famous for the paint sludge that Ford Motor company dumped near their territory, linked to contamination of food and water sources with lead and benzene, and nosebleeds, leukemia, and other ailments among tribal members.

Although New Jersey and New York recognize the Ramapough-Lenaape as a tribe, the federal government does not. When leaders applied for recognition in the 1990s, Donald Trump campaigned to stop them, concerned they would open gambling businesses to compete with his Atlantic City casinos. “I look more like an Indian than they do,” Trump said in 1995, after tribal members demonstrated outside Trump Tower. The federal government declined to grant status.

“In a sense we have seen the future under a Trump administration with the path he’s going toward, with rolling back regulation,” Owl said. “We’ve seen that future because that’s our past.”

Alleen Brown is a journalist and researcher. Her work has been published by The Nation, In These Times, YES! Magazine, and the Twin Cities Daily Planet in Minneapolis. Prior to joining The Intercept, Alleen worked as a researcher on Naomi Klein’s book This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate.

Spread the word