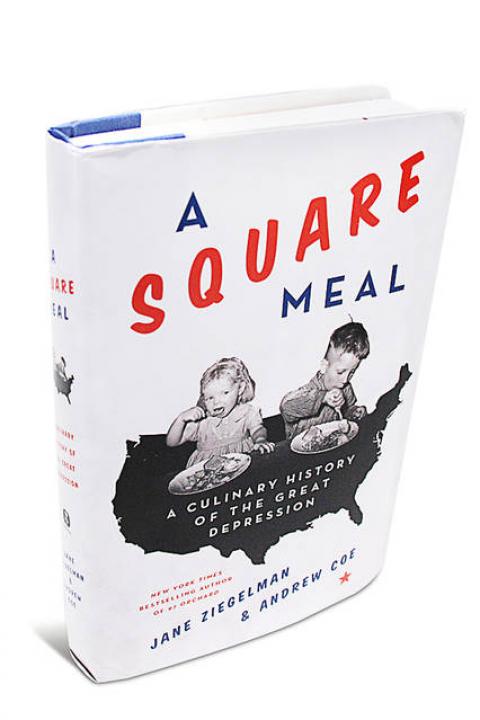

Not a day goes by without Americans being bombarded with conflicting advice about how to eat. Nutritionists deliver the latest information about fats and sweeteners while many food writers campaign for a return to the food that our great-grandmothers put on the table. This tension between scientific advice and traditional preferences can be traced back to the Great Depression, suggest Jane Ziegelman and Andrew Coe in “A Square Meal,” an absorbing account of how the Depression changed eating habits that is by turns amusing and sobering.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, immigrants and visitors alike expressed amazement at the abundance of American fare. In World War I, American troops received more food than any other combatants, as much as 4 pounds or 5,000 calories daily. But though America seemed the exception to the historical rule that intermittent hunger or even starvation was the norm, problems lurked. In growing cities, workers crowded into small apartments with kitchens so inadequate that inhabitants depended on street food, sandwiches or meals at soda-fountain counters. Worse, some children arrived in city schools too hungry to concentrate, men stood in bread lines all night, Southern sharecroppers grew sickly on a diet dominated by cornbread, and military recruiters turned away conscripts too malnourished to serve.

A loose coalition of Progressives believed that modern scientific research on nutrition offered the key to improving a misguided and wasteful American diet. In an impressive series of experiments at Wesleyan in the late 19th century, Wilbur Atwater had established baseline calorie needs and measured the calorific value of common foods. More recently, Elmer McCollum and others had figured out which vitamins and trace elements were important and argued that milk was the most perfect food. Armed with this information, nutritionists, home economists and politicians yearned to replace traditional foodways with a “scientifically designed eating program.” The Depression gave these reformers the opportunity not simply to try to avert hunger, Ms. Ziegelman and Mr. Coe write, but to interrupt the natural evolution of food habits and “in one colossal push” change the way America eats.

In the lead were home economists, who entered all spheres of public life.

Flora Rose, who along with her companion Martha Van Rensselaer dominated the home-economics department at Cornell, tried her hand at inventing new foodstuffs. Inspired by research at Columbia that showed feeding rats a mixture of dried skim milk and ground wheat increased their life span by 10%, she persuaded Ralston Purina to produce the fortified breakfast cereals Milkorno, Milkwheato and Milkoato. Rose and Van Rensselaer, with the support of their friend Eleanor Roosevelt, advocated adding them to everything from muffins to meatloaf, or even using them as a basis for chop suey.

Louise Stanley, with a doctorate in chemistry from Yale, headed the largest staff of female scientists in the country at the federal Bureau of Home Economics. They poured out advice to mothers nervous about what to feed their children and to relief workers struggling to design adequate menus. On the Agriculture Department’s farm-radio service, “Aunt Sammy” reassured women that they were indeed likely to be preparing an adequate diet and that frugal standbys like cracked wheat made sense. The home economist Hazel Stiebeling prepared a series of guides to diets for different income levels, including a “Restricted Diet,” heavy on bread and milk, to be used only in desperate circumstances.

Relief agencies, housewives and cooks translated this advice into rations and menus. A sharecropper family of five received a monthly allotment of 36 pounds of flour, 24 of split beans, 12 of cracked rice and 24 of cornmeal, along with lard, bacon, baking powder and half a gallon of molasses. A New York schoolchild could be sure that there was some milk in the lunch that might consist of cocoa, tomato purée, succotash, a cheese sandwich, and fresh or stewed fruit. Vagrants settled down to large, plain meals of lima beans and bacon, cold tomatoes, pickled onions, bread and butter, and tea.

The middle class, too, was urged to eat a similar, though more elaborate diet. They could turn to the Good Housekeeping Institute, run by the home economist Katherine Fisher, for advice about new appliances such as refrigerators and all kinds of canned foods, whose reputation as a resort for “lazy housewives” the institute’s magazine “worked hard to reverse.” They could also thumb the pages of the magazine for recipes such as jellied lime and grapefruit salad.

Ms. Ziegelman and Mr. Coe’s message is that long-term problems were in the making. They criticize Eleanor Roosevelt’s decision to express solidarity with a hungry nation by serving plain food at the White House. “Built on self-denial, scientific cookery not only dismissed pleasure as nonessential but also treated it as an impediment to healthy eating.” Given the backgrounds of the home economists, they view this outlook as inevitable. “The food authorities who led America through the Depression were overwhelmingly white, Anglo-Saxon women. . . . Who but a WASP could think up a diet based around milky chowders and creamed casseroles?”

By contrast, the authors praise two “gastronomic salvage missions.” In “The National Cookbook” (1932), Sheila Hibben argued for fresh, seasonal and regional American fare such as South Carolina hoppin’ John, Pennsylvania pandowdy and New England clam chowder. Then, although it did not make it into print, there was the WPA’s “America Eats!” project, which documented America’s rich tradition of communal dining at threshing dinners, church suppers, barbecues, fish fries and the like. “The National Cookbook” and “America Eats!,” conclude Ms. Ziegelman and Mr. Coe, were a defense against “science, efficiency, technology, consumerism . . . the onslaught of modernity.” Whether all readers will agree with their confidence in tradition over modernity remains to be seen.

Ms. Laudan is the author of “Cuisine and Empire: Cooking in World History"

Spread the word