Born on January 21 1876 to Armagh parents in Liverpool, James Larkin is forever linked to the trade union movement in Ireland and the 1913 Dublin Lockout but shortly after that episode in Irish history he went to the United States where he ended up in one of its most notorious prisons.

On November 7 1919 Larkin was one of a number of trade union figures arrested and charged with orchestrating anarchism. This was a time in which a red scare was sweeping the United States and the rounding up of left-wing leaders and sympathisers was a common feature and by 1919 there was a severe crackdown on people such as Larkin.

When Larkin arrived in the United States he got involved with the Industrial Workers of the World (Wobblies) and joined the Socialist Party of America but his membership was revoked in 1919 when he became too “radical” and supported the Bolshevik Revolution.

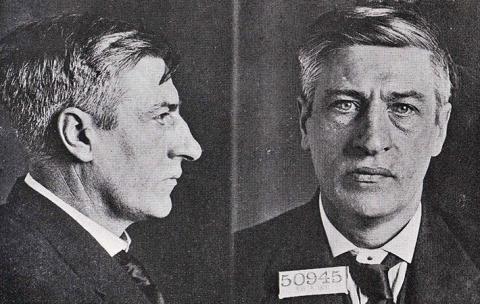

When Larkin was arrested and charged with “criminal anarchy,” he stood trial where he was found guilty of subversive behaviour and sentenced to between five and 10 years hard labour in Sing Sing prison.

Visits from family and friends were restrictive for prisoners in Sing Sing and even more so for a prisoner like Larkin, who had almost caused a riot in the prison yard during his first year there.

In the prison exercise yard, Larkin gave a fiery speech on St Patrick’s day in which he declared the snakes that St Patrick had driven from Ireland had ended up in places like the United States where they evolved into policemen and prison guards.

Despite the restrictive regime regarding visitations for prisoners at Sing Sing, the Hollywood actor Charlie Chaplin managed to get access into the notorious prison and even rarer, he managed to get a meeting with Larkin.

Chaplin had been in New York on a short break when he and his friend, the writer Frank Harris, decided to make their way to Sing Sing prison some 30 miles north of New York City to see the incarcerated Larkin. Both Chaplin and Harris were of the opinion that Larkin was unjustly locked up and when they arrived at Sing Sing, Chaplin used his movie star credentials to convince the warders to let them meet convict 50945.

In his autobiography, Chaplin described Larkin as “a brilliant orator who had been sentenced by a prejudiced judge and jury on false charges of attempting to overthrow the government.”

When they entered Sing Sing prison, Harris and Chaplin were guided to the boot factory in the prison where Larkin was working and the three men held a brief meet and greet under the strenuous eye of warders. The men spoke of current affairs, prison conditions and Larkin spoke of his family whom he had not heard from since his incarceration.

The meeting with the locked up labour activist had left an impression on Chaplin and afterwards he sent a gift parcel to Larkin’s wife and children which included a pair of moccasin beaded slippers for Mrs Larkin.

Chaplin’s visit to Larkin in Sing Sing left the actor with a degree of sympathy for prisoners and he returned there again in 1932 with a reel of his new film City Lights to showcase to those incarcerated there. In his autobiography, Chaplin wrote how his visit to Larkin in Sing Sing opened his eyes to such harsh prison conditions. He described the prison as “grimly medieval” where “the human spirit was suspended” and wondered “what fiendish brain could concieve of building such horrors!”

In 1923 New Yorkers elected Irish-American Al Smith as their new governor and one of his first acts in office was to pardon Larkin on the grounds that he was not a criminal with violent tendencies. J Edgar Hoover of the FBI oversaw Larkin’s release and subsequent deportation on board a liner bound for Southampton.

By the time Larkin arrived back in Ireland, it had become a very changed country. A Free State had been established on a bedrock of conservative Catholicism. Larkin’s left-wing confidant James Connolly was dead and with him in the grave was any hope of a socialist republic. The Irish Labour party Larkin left behind had buried the spirit of socialism and Larkin found himself at complete odds with it.

Big Jim Larkin died, 70 years ago, in his sleep at Meath hospital on the January 30 1947. He was buried in the famed Glasnevin Cemetery where his headstone simply states: “James Larkin, the labour leader.” On Dublin’s main thoroughfare, O’Connell Street, there stands a prominent statue of Larkin, right outside the General Post Office and often a focal point for protesters to gather and display their disgust against unfairness and unjust ways.

The inscription on the Larkin statue is a short extract from one of his speeches and is translated in Irish, French and English: “The great appear great because we are on our knees. Let us rise.”

Spread the word