You could call the men and women at Viome factory workers, but that wouldn’t be the half of it. Try instead: some of the bravest people I’ve ever met. Or: organisers of one of the most startling social experiments in contemporary Europe. And: a daily lesson from Greece to Brexit Britain, both in how we work and how we do politics.

At the height of the Greek crash in 2011, staff at Viome clocked in to confront an existential quandary. The owners of their parent company had gone bust and abandoned the site, in the second city of Thessaloniki. From here, the script practically wrote itself: their plant, which manufactured chemicals for the construction industry, would be shut. There would be immediate layoffs, and dozens of families would be plunged into poverty. And seeing as Greece was in the midst of the greatest economic depression ever seen in the EU, the workers’ chances of getting another job were close to nil.

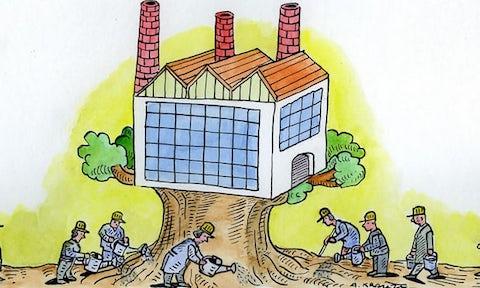

So they decided to occupy their own plant. Not only that, they turned it upside down. I spent a couple of days there a few weeks back, while reporting for Vice News Tonight on HBO, and it now looks like just an ordinary factory. Behind the facade, it has become the political equivalent of a Tardis: the more you look inside, the bigger the implications get.

For a start, no one is boss. There is no hierarchy, and everyone is on the same wage. Factories traditionally work according to a production-line model, where each person does one- or two-minute tasks all day, every day: you fit the screen, I fix the protector, she boxes up the iPhone. Here, everyone gathers at 7am for a mud-black Greek coffee and a chat about what needs to be done. Only then are the day’s tasks divvied up. And, yes, they each take turns to clean the toilets.

Let that sink in. A bunch of middle-aged men and women who have spent their entire careers on the wrong end of barked orders about what to do and when to do it have seized ownership of their own workplace and their own working lives. They became their own bosses. And they immediately align themselves to principles of the purest equality possible.

“Before, I was doing only one thing and had no idea what the others were doing,” is how Dimitris Koumatsioulis remembers the factory when he started in 2004. And now? “We’re all united. We have forgotten the concept of ‘I’ and can function collectively as ‘we’.”

The other massive change that has taken place is between the factory and its neighbours. When the workers “recuperated” their workplace (to use the local term), they could only do so with the help of Thessaloniki locals. Whenever representatives of the former owners came to requisition their equipment, as a court had given them permission to do, hundreds of residents would form a human chain in front of the plant (I contacted lawyers for Viome for comment but, despite assurances, no statement was forthcoming).

When the workers consulted the local community about what they should start to produce, one request was to stop making building chemicals. They now largely manufacture soap and eco-friendly household detergents: cleaner, greener and easier on their neighbours’ noses.

Staff use the building as an assembly point for local refugees, and I saw the offices being turned over to medics for a weekly free neighbourhood clinic for workers and locals. The Greek healthcare system has been shredded by spending cuts, its handling of refugees sometimes atrocious; yet in both cases, the workers at Viome are doing their best to offer substitutes.

Where the state has collapsed, the market has come up short and the boss class has literally fled, these 26 workers are attempting to fill the gaps. These are people who have been failed by capitalism; now they reject capitalism itself as a failure.

Another old-timer, Makis Anagnostou, talks of how their factory is proof “that an alternative economy is feasible”. Contrast this with the way we normally think about work. At any large factory or office, security guards keep the outside world at bay. You check your politics at the door, and listen to your line manager. We even talk about work-life balance as if the two were polar opposites. At Viome, they are combined. One of the results is a strong bond of loyalty between the workers and their community.

The evening I arrived, swarms of people turned up for a fundraiser. They sat on plastic chairs in the middle of the storage warehouse and watched a play by Dario Fo, enacted by a national theatre company. The lead actress altered some of the lines to refer to this place and its business: “They sell their soaps everywhere. And everyone is buying it!” Cheers broke out among audience members, alongside some fervent dabbing of eyes.

Viome is precious. It is also precarious. From the roof of the building, you can see the huge site owned by the parent company. It used to employ about 350 people; now the 26 men and women operate out of one small corner of the lot.

They earn the same amount as they would receive in unemployment benefit. And when night falls, one of the workers stays on to stand guard – just in case the old owners come back. During the day, a line of empty barrels acts as a barricade.

For all its fragilities, Viome still offers a lesson in politics to any British visitor. In the year since the EU referendum, Britons have entered an era of bullshit sovereignty. Sofa-loads of politicians claim they “get it”. They pretend to listen – yet hear only the answers they want. Dissenters are told they are “talking Britain down”. Any actual outbreaks of democracy, such as members of the Labour party wanting more of a say over their representatives, are leapt upon as an instance of mob rule.

Meanwhile, politics in Britain is retailed as what one would-be alpha Tory said to another at some champagne reception.

From Thessaloniki, you see all of that as the lie it is. Take back control? Just a means of allowing Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson some prime-time gurning. Referendums? Stuffed with lies and alarmism. If you’re tired of ex-public schoolboys playing at populism, come and see what democracy looks like when exercised directly by the people themselves. Come to Viome.

Spread the word