During that time, Wesleyan College was silent. The college in Macon, Ga., talks about its history quite a lot, pointing with pride to its status as the first institution chartered (in 1836) to award college degrees to women.

But an unusual part of its history was revealed Thursday by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution: decades in which the traditions of the Ku Klux Klan played a key role in campus life, with at least one tradition ending only in this century.

Wesleyan today is diverse: about a quarter of students are from outside the United States, and about one-third (most of them black) are American minority women. But only Thursday did the college acknowledge its past.

"Wesleyan College’s history includes parts that are deeply troubling, and we are not proud of them," a statement from the college said. "When Wesleyan was founded in 1836, the economy of the South was based on the sin of slavery. We are sorry for the pain that parts of our past have caused and continue to cause. We also celebrate how far our college has come and how we are striving to become the inclusive community we are called to be."

The statement goes on to note the Klan influence: "Wesleyan’s people were products of a society steeped in racism, classism and sexism. They did appalling things -- like students treating some African-Americans who worked on campus like mascots, or deciding to name one of their classes after the hate-espousing Ku Klux Klan, or developing rituals for initiating new students that today remind us of the Klan’s terrorism."

Among the details revealed by the Journal-Constitution:

- Classes long gave themselves names, and the names selected by the classes of 1909, 1913 and 1917 were the "Ku Klux Klan."

- The yearbook in 1913 was named "Ku Klux."

- In the early 1900s, students marched in Klan garb through the streets to initiate students into the KKK.

- For decades, through the 1990s, the athletic teams were called the Tri-Ks (for the KKK), later changing to the Tri-K Pirates before dropping the Klan reference.

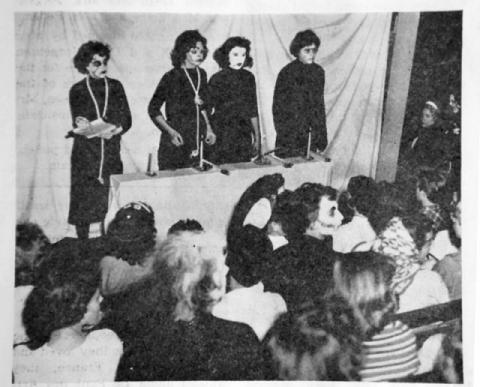

- In the 1950s (photo above), hazing rituals for new students (run by students) featured women with painted faces and carrying nooses.

- As recently as 2006, a student group wore hooded purple robes for an initiation event for new students -- and that robed activity ended only around 2010 or 2011.

The first black students to graduate from Wesleyan were admitted in 1968.

The story in the Atlanta paper came about because Brad Schrade, an investigative reporter for the Journal-Constitution, was shown a copy of the college's 1913 yearbook. Wesleyan, which was starting to study its own history at the time, gave him access to archives that he used for his research. His article indicates that black student groups had periodically raised questions about the college's history and traditions before now.

A False Impression?

Vivia Lawton Fowler, Wesleyan's provost, will become president of the college on July 1. In an interview, she said that the article by the Atlanta newspaper was "fair and balanced," but that she viewed the Klan ties over the years as belonging to students, not the institution. Fowler said the college is nearing the end of a two-year period of studying its history and was planning to issue a statement at some point in the fall, as well as to update the college's history page on its website.

"It's going to appear that all of this work that we were going to roll out in the fall was in response to the article," she said, when that's not true.

Fowler said that she did not believe any student or college activities going on today reflect the Klan culture that was once a powerful force at the college.

The past semester has been one of significant discussion at the college about issues of diversity and inclusion, she said. Much of the discussion was prompted by incidents that took place shortly after President Trump proposed his ban on travel to the United States by students from seven countries (after the ban was rejected by federal courts, Trump issued a revised ban, also now on hold due to court rulings, covering only six countries).

Amid discussion of the travel ban, the college reached out to its international students, Fowler said. None of them were from the countries covered by the ban, but the college wanted them to know that they were welcome and wanted at the college. As those activities took place, someone wrote "Go home" with "#Trump" on the whiteboard of an international student.

As word of that incident spread, someone wrote an inflammatory racial slur on a wall in a dormitory. The college then called off classes for the next day so students and faculty members could discuss the issues raised by the incidents. The college has investigated the incidents but has not found those responsible.

Fowler said that these discussions reinforced the view of college leaders to talk "about parts of our history that we are not proud of."

Other Colleges Debate the Klan

Klan history has come up at a number of other colleges in recent years. In most of the cases, the issue has been statues or buildings that honor people who had Klan ties. Among the developments:

- The University of Oregon in 2016 removed the name of Frederic Dunn from a dormitory that has for years honored him. Dunn was a professor of classics at the university in the 1920s and 1930s and was respected for his teaching and scholarship. He was also a leader -- with the title “exalted cyclops” -- of the Ku Klux Klan in the region.

- Middle Tennessee State University in 2016 announced plans to change the name of Forrest Hall, which honors Nathan Bedford Forrest, a Confederate military leader who went on, for a time, to be a leader of the Ku Klux Klan.

- University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2015 changed the name of Saunders Hall, which since 1920 had honored William L. Saunders, a Reconstruction-era leader of the Ku Klux Klan. Carolina board members said they believed it was a mistake for the board in 1920 to say that Saunders's Klan ties were worthy of honoring.

- In 2010, after research conducted by a professor drew attention to the history of William Stewart Simkins, the University of Texas at Austin removed his name from a dormitory. Simkins was a longtime law professor at Texas, but before that, he and his brother helped organize the Florida branch of the Ku Klux Klan -- an organization he defended throughout his life, including while serving as a law professor.

Not Just the South

John Thelin, a professor at the University of Kentucky and author of A History of American Higher Education, said that the reports on Wesleyan did not shock him because the Klan was, for a time, quite active nationally. He stressed that Klan support was "very strong" in the Midwest.

The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign had a student chapter of the Klan in the early 20th century. And Thelin noted that the Klan's bigotry had influence in higher education in the Midwest. Bias against Roman Catholics played a big role in the Big Ten's 1926 rejection of a membership bid by the University of Notre Dame, he noted.

Thelin also noted similarities in the Klan's views of socializing people and maintaining secret initiation procedures with the histories of some fraternities. But Thelin said that the Klan had limited scope in terms of influencing college students in part because the Klan was "initially an undereducated group."

Scott Jaschik, Editor, is one of the three founders of Inside Higher Ed. With Doug Lederman, he leads the editorial operations of Inside Higher Ed, overseeing news content, opinion pieces, career advice, blogs and other features. Scott is a leading voice on higher education issues, quoted regularly in publications nationwide, and publishing articles on colleges in publications such as The New York Times, The Boston Globe, The Washington Post, Salon, and elsewhere. Scott served as a mentor in the community college fellowship program of the Hechinger Institute on Education and the Media, of Teachers College, Columbia University. He is a member of the board of the Education Writers Association. From 1999-2003, Scott was editor of The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Spread the word