As Vietnamese Americans who arrived as refugees or as children of refugees, many of us grew up focused on survival. We also grew up afraid to ask questions - about the war, why our families were here in the U.S., and what this means for our communty. Our confusion and curiosity would oftentimes be met by elders with silence, pain, and, occasionally, anger. Some of us found partial answers in the communities we gew up in, through our connections to temples, churches, small businesses, and important events like Tet. But for many there remained a sense that the stories were incomplete or unclear, that there were things still left unspoken.

Our politicization often came through transformative, lived experiences, community education, and exposure to Asian American studies classes, which helped connect us to deeper histories and identities but would oftentimes be a greater source of confusion. We learned about social justice movements in the U.S., including antiwar efforts that offered a drastically different perspective of what happened in Viet Nam that we had been told growing up. And all the while, even as we were developing our activism and commitment to social justice, we knew in the back of our minds that our beliefs and ideologies were growing in a direction that in many ways conflicted with those of our families and our communities.

As adults, many of us would continue our political work. We became active in organizing with Asian and Pacific Islander communities as well as other communities of color around a range of issues and campaigns. These experiences also started to connect us to one another as progressive/left Viets doing social justice work while also beginning to engage in the complexities of our own hxstory and identities.

The intensely personal work of attempting to reconcile our identities as progressive/leftists and as Viet has often been accompanied by a sense of isolation, a dread of opening deep wounds, and a real fear of the potential ramifications that come from challenging the dominant narrative. It has only been through forming connections with other like-minded Viets that we have been able to build bridges within ourselves, with one another, and with the broader community.

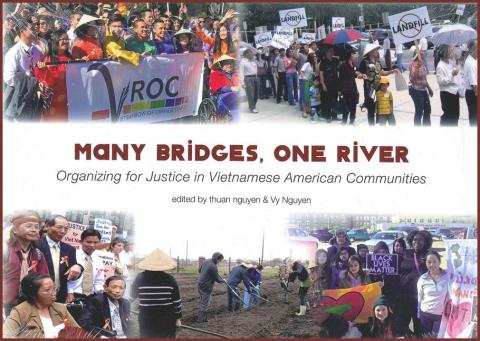

Many Bridges, One River is a reflection of this oftentimes tumultuous journey that, we hope, captures some of what can happen when we engage directly in the questions of where we've been, who we are, and what kind of world we want to create. The stories and lessons in this book offer insights and strategies on ways to move forward and are a testament to what is possible when we are allowed to ask questions - greater compassion and connection, a more critical understanding of hxstory, and a deeper sense of community and self.

The genesis of this book can be traced back to a key moment in 2010, when a group of Viet progressives and leftists in California - organizers, students, activists, artists - held a statewide convening that brought fifty of us together for the first time. There was a collective sense of joy in finding each other and in explicitly discussing what it meant to be progressive/left and Viet. We worked in social justice nonprofits and volunteer groups, labor unions, and arts collectives, in different geographic and cultural/racial communities, but rarely within our own Viet communities.

Together we explored our community's hxstory of red-baiting and political violence as a constant reminder of the very real potential risk and danger - from alienation from family, friends, community, to slander and threats, to physical violence. We collectively acknowledged our progressive/left politics and our Viet identities, which was something that we mostly kept separate and oftentimes hidden. This gathering was a powerful reminder that we could no longer stay silent.

Forty years after the Fall of Saigon in 1975 and the unification of Viet Nam, there are nearly 1.8 million Vietnamese Americans in the U.S., making us the fourth largest Asian American group and the sixth-largest foreign-born population. The Republican Party has continued to invest in our community, grooming a new generation of conservatives like Van Tran in Orange County and Joseph Cao in Louisiana for political office and using them as a wedge against other communities of color. The fact that a small subgroup of Viets had entered into the professional class was being used by the Right to characterize us as a classic model minority success story.

At the same time, the Republican stranglehold seemed to be showing cracks. In the 2008 presidential election, Vietnamese Americans as a whole voted in favor of John McCain over Barack Obama at a rate of 67 percent to 30 percent, but Obama won 69 percent of the vote among Vietnamese Americans born in the U.S. And, in the wake of Hurricane Katrina and the BP oil spill, the Gulf Coast Viet community was visibly organizing and speaking out for social justice, drawing Viets from across the country compelled and inspired to contribute in whatever way possible to rebuilding efforts.

What we began to learn when we came together at the 2010 convening was that we have a hxstory of left organizing in the U.S. dating back to the 1970s. It also became apparent in our conversations that most present-day community-based progressive work in the Viet community began to emerge around the early 2000s. Since then, there has been a marked increase in Viet social justice efforts, with organizations and projects sprouting up in California, the Gulf Coast, the Northeast, and the South. There have also been recent shifts in the poltical landscape of Little Saigon in Orange County, California, which is home to the largest Viet community outside Viet Nam.

Since the 2010 convening, Viet organizing and activism has developed in the context of immigrant and refugee rights, climate justice, Occupy Wall Street, the Movement for Black Lives, efforts of the Oceti Sakowin Camp to halt the Dakota Access Pipeline, and ongoing people's movements around the world. The 2016 election saw the activation of white supremacist, xenophobic, misogynist, and homophobic elements in the country with the ascension of a president that emboldened these oppressive forces. However, this is the first time in hxstory that a president will have won the electoral college while losing the popular vote by 2.9 million votes - with people of color, including Vietnamese Americans, voting overwhelmingly against him. It is also notable that during the primaries an explicitly democratic socialist candidate garnered considerable and enthusiastic support across the country. These developments continue to offer opportunities for deeper discussion and engagement beyond what we've known for the past forty years and heighten the urgency to act. Vietnamese Americans today - at a time of catstrophic and unsustainable gobal inequality - have a choice to align ourselves either with the forces of rightwing extremism that threaten to accelerate privatization, poverty and violence, or with the emerging promise of a progressive majority in the U.S. and with international movements for peace and justice.

Our belief is that organizing within the Viet community is critical. Forty years after the end of the war, we find ourselves - from Oakland, California to Biloxi, Mississippi, to Charlotte, North Carolina - as part of the growing 99 percent, living next to poor Black, Latino, Native American, Asian, and white families. Our communities have different histories, but we share a deep, multigenerational trauma from our respective experiences with violence and oppression. We have a perspective to contribute to the crucial dialogue about the future of our communities. Given our hxstory, what would we say about the seemingless endless militarism justified by the War on Terror? About the growing repression of civil liberties and dissent? About police brutality and mass criminalization when Vietnamese youth face one of the highest rates of incarceration among Asians? About race, when we continue to be used as model minorities to bolster white supremacy? About wealth distribution and capitalism, when Vietnamese have some of the highest poverty rates among all groups in the nation, and when Viet Nam continues to experience greater disparities under the pressures of globalization? About climate change when Hurricane Katrina showed the vulnerability of marginalized communities in disasters and when Viet Nam is likely to experience catastrophic rising sea levels? The Viet community has a clear stake in building a just society for all.

The title of this book Many Bridges, One River, reflects the complexities of organizing in the Viet community as well as a deeper connectedness we all share. This book is intended for an audience of fellow organizers and allies with the goal of supporting the burgeoning organizing work in Vietnamese American communities. As the editors and as Vietnamese Americans invested in social justice, we wanted to capture an oral hxstory of Viet progressive/left organizing in the U.S., and to begin to broaden the dominant, mainstream narrative about Vietnamese America. We also want the book to be a useful tool for those doing social justice work in Viet communities by exploring the on-the-ground challenges facing Viet organizers and by sharing their strategies and best practices. We hope that the book will be a catalyst for discussions that support the work and that continue to build a Viet left analysis and organizing infrastructure. By doing this, we seek to move beyond the silence that often exists in Vietnamese American political spaces.

We want ot recognize that valuable books with oral hxstory and interview collections of Vietnamese Americans have been published before this that primarily focus on documenting the migration and life experiences of first- and 1.5-generation community members. In addition, Organizing on Separate Shores by Kent Wong and An Le specifically highlights union organizers in the U.S. and Viet Nam. With this book, we hope to continue to expand the narrative of who we are and add to the small but growing collection of stories by and about the community with a specific focus on the complexities of organizing for social justice and community transformation in Vietnamese America.

In reading these interviews, what shines through is the creativity, resilience, and heart of these organizers, and their love for community. As Viet organizers, they share openly about struggles with red-baiting, sexism, homophobia, intergenerational differences, language barriers, burnout, and the loneliness that can come with being one of the few in their field. Their strategies and advice in navigating these dynamics are often marked by willingness to experiment, hustle, and "make the road by walking." Many of the organizers interviewed also see their political work in the Viet community as part of a personal journey to begin to heal from trauma and come to terms with their own hxstory, famiy obligations, and ideological contradictions. Several connect the process to their spirituality and faith. Many stress the need for more focus on self-care and support networks.

Organizers consistently bring up the challenge of navigating the community's tight political spaces from the perspective of a progressive/left ideology. For some, their approach has been to avoid potentially divisive ideological discussions altogether and focus on the concrete issues and conditions at hand. Others are experimenting with political education with community members who bring in a broader analysis, though the conversations can be risky. These various approaches revolve around the implicit assumption that many of us carry: in order to work with the Viet community, we can't be too political. As organizing in the Viet community progresses, the question deserves ongoing discussion, along with an acknowlegement of the real and lasting impact this reality has had on our development as a community. While being grounded in the community, how do we nevertheless carve out political space? How do we ensure our work is informed by a deeper analysis and not driven by the fear of backlash? How do we connect to communities and issues beyond our own toward a broader movement for justice?

The interviewees also raise questions about the future of social justice work in the Viet community. One concern - common to organizing in general but acutely felt here - is about how to create and sustain a progressive Viet infrastructure when the work is greatly under-resourced and understaffed. Organizers talk about the role of volunteer and nonprofit organizations and the importance of building a leadership pipeline. They also anticipate the evolution of Viet identity as young Viets in the U.S. and in Viet Nam become more globaly conscious in their outlooks and more connected with one another through increased access to information and communication.

Ultimately, we hope this collection of interviews sheds some light on the promise and the ongoing work of building a progressive/left Viet infrastructure in the U.S., with an eye toward the broader project of social and economic transformation for all. In many ways, this book is a call to action. Vietnamese hxstory is a more than 2,000-year-old story marked by a long succession of colonial domination, war, and struggle. At the same time, it is full of warriors, patriots, engaged Buddhists and faith workers, youth, artists, farmers and revolutionaries who in one form or another all fought for their humanity and their liberation. Today, our ability to organize ourselves as Vietnamese Americans and to ally with other communities is an essential contribution to our collective struggle for these very same goals.

Moderator's Note: Read this book!

To order Many Bridges, One River from the Asian Studies Center at UCLA: http://commerce.cashnet.com/aasc. After page opens, click on the link "Asian American Firsts". Many Bridges, One River will appear as option to purchase for $15 per copy.

Thuan Nguyen is the youngest of eleven children who immigrated with his family from Vietnam to Virginia in 1975, moving later to Oregon and then to California. Thuan has participated in community work for many years as an organizer, case worker, advocate and mentor inn various organizations addressing youth, education reform, affordable housing, immigrant and refugee rights, LGBTIQ justice and multiracial coalition building.

Vy Nguyen immigrated from Vietnam with her sisters and parents in 1979 first to Kansas, then Texas and California. She has organized with lower wage workers in Koreatown in Los Angeles as well as for many years with living wage, immigration reform, accountable development and educational equity campaigns. She is a recognized writer and journalist. She currently works in philanthropy.

Spread the word