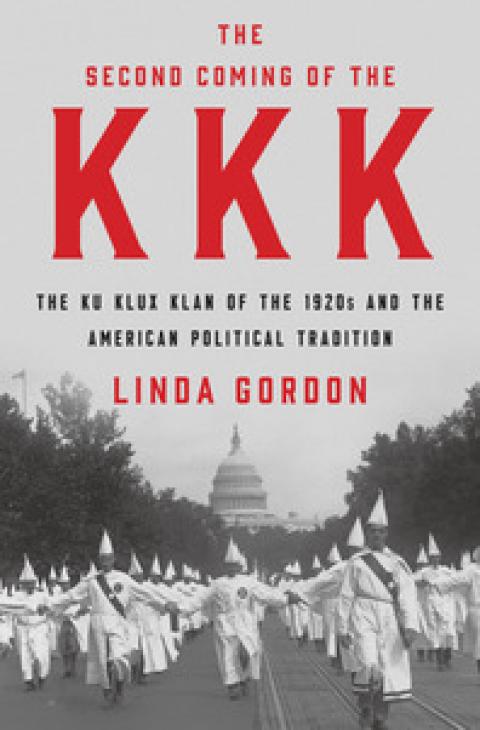

The Second Coming of the KKK

The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition

Linda Gordon

Liveright

ISBN 978-1-63149-369-0

Scholarship on the Ku Klux Klan long ago reached the stage of high granularity, with monographs focusing on the state and local level (there is a book-length study of the Klan in Utah, for example, and one focusing on El Paso, Tex.) even to the point of scrutinizing the membership and activity of a single klavern, since the occasional stash of records and memorabilia will turn up in an archive in someone’s attic.

The Klan’s demographics have been analyzed. The legacy of Klan feminism has been unearthed, surely to great embarrassment in both camps standing to inherit it. As much of the history of the Klan in Canada has been chronicled as anyone is likely ever to need. No scholarship addresses the Klan in LGBT studies, to the best of my knowledge, but watch this space.

So The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition (W.W. Norton and Company), by Linda Gordon, a professor of history at New York University, is a late addition to a very crowded shelf. The book makes its contribution chiefly as a work of synthesis; its endnotes point, for the most part, to earlier studies rather than primary sources. An overview of the subject is valuable, especially given the natural tendency of monographs to stress what distinguishes one region’s KKK from others. Klansmen in Utah in the 1920s, for example were non-Mormons who (big surprise) hated Mormons, who in El Paso were not an issue. Gordon bends the stick the other way, emphasizing broad patterns. And this has the effect of making the book more timely than even the headlines of the past few days would suggest.

Referring to the KKK in the singular, as “the Klan,” is both a convenience and somewhat misleading. Klan activity has gone through three distinct phases over the past 150 years -- with so little continuity of personnel between them that we’re really talking about three distinct organizations. They share certain symbols, rituals and hatreds, of course, deriving from the original group that took shape in the South during the early years of Reconstruction. This was a fraternity (its name deriving from the Greek kuklos, circle) devoted to terrorizing African-American freedmen and anyone helping to secure their rights.

It was a relatively small and short-lived group. The second Klan emerged in the wake of D. W. Griffith’s blockbuster Birth of a Nation (1915), which depicted the KKK as a valiant band of heroes. In adapting from Thomas Dixon Jr.’s novel and play, Griffith seems to have grasped that the material had great as well as dramatic potential. The robes and burning crosses of the original Klan were meant to terrify, but on screen they were spectacular. Furthermore, the spectacle reached an audience of millions across the entire country.

The 20th-century Klan had a few lackluster years before it took off in the early 1920s, with an updated message of nativism, anti-Catholicism, anti-Semitism and the need to preserve traditional family values from the influence of liberal elites. (Also, apparently, Mormons.) At its peak, the Klan claimed to have four to six million members or more -- a figure only credible if it includes four or five million who signed up during a recruitment drives and then quit after a couple of meetings. If so, that would leave a million members, out of a population that the 1920 census determined to be 106 million. Up to 50,000 to 60,000 of them turned out in full regalia to march on Washington, first in 1925 and again the following year.

It was downhill from there. Scandals and clique warfare took their toll. By the onset of the Depression, the second Klan was effectively finished as an organization of national scope. The civil rights movement inspired a revival of sorts -- though without anything like the second Klan’s growth rate or public clout. Warning of a new, revitalized KKK -- one using the latest resources to spread its influence and menace -- spring up every few years. David Duke managed to become a name known to everyone in America (except, it seems, Donald Trump). But every such development should be kept in perspective. A shared commitment to white supremacy only counts for so much given all the bad blood. The third KKK inherited the tendency to fragmentation evident by the late 1920s -- intensified by each Klan’s certainty that other Klans are full of FBI and ADL agents.

The mass movement depicted in The Second Coming of the KKK can be unnerving to study not for its hatreds but for its normality. Then, as now, liberals are liable to pathologize such a movement. But the political and cultural beliefs of Klansmen -- that immigrants were stealing their jobs, for example, or that white Protestants were becoming almost powerless in “their own country” -- were widespread enough to count as mainstream.

The Klan was wholeheartedly in favor of both Prohibition and women’s suffrage. It encouraged church attendance; its hostility to science did not mean KKK members were anything but enthusiastic for the technology and commodities it enabled. Expressing the conviction that the pope was living secretly in the United States and would soon ascend a gold throne to proclaim himself the country’s ruler might make some neighbors suspect you were crazy. Yet plenty who thought so might be worried by reports that the daughters of Irish immigrants were becoming schoolteachers in order to bring the public schools under Catholic influence.

At the same time, the Klan of the 1920s put enormous emphasis on civic-mindedness. It organized picnics and carnivals. There were Klan baseball teams, some of them semipro. “The Youngstown team challenged the Knights of Columbus,” Gordon writes, “and the Klan played Wichita’s ‘crack colored team,’ the Morovians (the Klan lost) … In Los Angeles, the Klan team played a three-game charity series against a B’nai B’rith team, and in 1927 in Washington, D.C., the Klan played against the Hebrew All-Stars …”

It is not the use of baseball bats one expects from the Klan. It all sounds dismayingly wholesome. At the same time, this was an organization which, while focused on plenty of other racial grievances, also considered the relative merits of re-enslaving and exterminating black people. How Gordon understands the inner coherence of a political culture with such seemingly contradictory traits is the topic for next week.

Scott McLemee is the Intellectual Affairs columnist for Inside Higher Ed.

Spread the word