After 47 years, the old black-and-white news photograph can still shock: A helmeted Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputy points a teargas gun toward a small unarmed group crowded in the doorway of the Silver Dollar Café, a tavern on Whittier Boulevard in East L.A. It’s a local pub, next door to a wig shop, with an outer wall advertising itself as a swinging destination with a collage of cartoon martini glasses, musical notes and topless women. But that afternoon in 1970, it was just someplace to grab a beer for journalist Ruben Salazar before heading back to the office.

He’d spent the day covering the National Chicano Moratorium March against the Vietnam War, which ended with deputies breaking up the demonstration and clashing with protesters. But Salazar, 42, a columnist for the Los Angeles Times and news director at the Spanish-language station KMEX-TV, never made it out of the Silver Dollar. Moments after the photograph was taken by Raul Ruiz of the underground La Raza newspaper, the deputy blindly fired a teargas canister into the bar, striking Salazar in the head and killing him instantly.

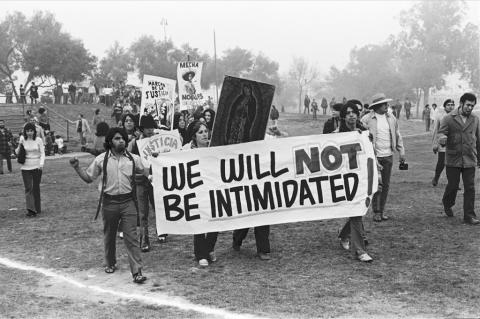

That picture is now at the center of LA RAZA, a photographic exhibition at Los Angeles’ Autry Museum of the American West that was culled from an archive of 25,000 images created for the publication between 1967 and 1977. During those years, La Raza evolved from a small tabloid newspaper into a slicker magazine, but the mission never wavered: representing the Chicano community at a time of political upheaval and demands for civil rights.

The exhibition, which runs through February 10, 2019, shares La Raza‘s photographic collection for the first time with the public. It is now part of Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA, the Getty’s countywide exploration of Latin American and Latino art, where the recently unearthed photographs offer an essential document of a movement too often overlooked.

“The purpose of the newspaper-magazine was that of an organizing tool, first and foremost,” says Luis Garza, who was then a young photographer on the all-volunteer staff, and co-curates the Autry show. “There was little representation whatsoever of the Chicano community … within the body politic of Los Angeles. Decisions were being made affecting our community that we had no voice in.”

Many of the images at the Autry depict a community newly engaged with the political moment, filling city streets in protest and carrying signs that confronted issues of immigration, cultural identity, civil rights and foreign wars that remain relevant a half-century later. In one picture, protesters march past the stately Times building in downtown L.A., with one sign reading, “Stop Nixon’s racist deportation raids.”

Other photographs document marches through rural California, beneath banners for the United Farm Workers and the slogan “Be Brown & Be Proud.” Teenagers take to the streets in pictures from a series of walkouts and “blowouts” at several L.A. high school campuses named for presidents Wilson, Jefferson, Garfield, Lincoln and Theodore Roosevelt. Also at the Autry: A row of large blowups of police officers on rooftops and bridges, watching with binoculars, cameras and rifles as the demonstrations unfolded. La Raza was there to report on a community speaking out and under siege.

There were consequences for the mostly young staff. One prominent photograph at the Autry captures a little girl in braids, yelling into the lens while holding a stack of La Raza newspapers with an alarming headline: “La Raza Raided — Editor, Staff Imprisoned.” Another picture shows La Raza photographer Ruth Robinson being handcuffed along with a Brown Beret activist.

“They got arrested all the time,” says Amy Scott, chief curator at the Autry and co-curator of LA RAZA. “For them, activism and photography were not two separate things. The photographs were a way of making these arguments and putting them out there.”

The mission was not simply to document the era’s homegrown political uprising, but to capture something of the culture asserting itself as “a much more complex and dynamic community than had ever been portrayed in the mainstream media,“ adds Scott.

La Raza began life in the basement of an Episcopalian church in Lincoln Heights, debuting September 4, 1967, as a modest eight-page publication. By the time it had grown to more than 60 pages, its focus had expanded beyond local issues to concerns about Vietnam, indigenous land rights, immigration and Latin America. Mainstream media in the late 1960s was dependably conservative and “gave no coverage to our community whatsoever except to depict us in a negative light,” says Garza.

The photographers at La Raza provided their own cameras and 35mm film, while editors struggled to keep the no-budget operation afloat. “We tried at first to be bi-monthly, then it became monthly, then it became whenever you had the funds to print,” recalls Garza, a University of California, Los Angeles student at the time. “It could be weeks, months or even a year before the next issue came out.”

The paper’s most dramatic moment of recognition came with the Moratorium March and the death of Salazar. After working as a foreign correspondent in Vietnam, the Times reporter returned to Los Angeles to find a vibrant subject in the growing Chicano movement. He was often critical of police — and was one of four fatalities on a violent day of deputies clashing with protesters. Pictures at the Autry show police clearing streets with batons and shotguns, and of squad cars with shattered windshields.

After Salazar’s body was carried out of the Silver Dollar, the L.A. Sheriff’s Department denied any role in his death, even suggesting that snipers were responsible. It was La Raza‘s photographs of the shooting, also published in the Times, that revealed the truth. Some suspected Salazar had been targeted for assassination. Whether through malice or utter incompetence, the incident was a bleak example of law enforcement’s posture within East L.A. The deputy who fired into the bar was never charged.

In 2012, Garza and others began an effort to go through the La Raza photographs, which had been largely unseen and stored in multiple three-ring binders by one of the founding editors. Images had to be identified and cataloged, a process Garza describes as “photo-forensics.” The archive was placed at the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center, and with a grant from the Getty, the pictures were digitized, culminating with the Autry exhibition.

“I view it as karma and the blessings of the gods,” Garza says of the successful effort to bring the pictures back into circulation after four decades in storage.

“The reaction from everyone is very positive, it’s very emotional,” adds Garza, who went on from La Raza to documentary work for KABC-TV. “For the first time we’re getting recognition of who we are, what we accomplished and what we attempted. It isn’t just about our community as Chicanos. It is about Los Angeles. It is about this country as a whole.”

LA RAZA, Autry Museum of the American West, 4700 Western Heritage Way, Los Angeles; through Feb. 10, 2019. theautry.org

Steve Appleford was a features editor for Times Community News and a contributor to the Los Angeles Times Calendar section. He is a Los Angeles native and the former editor-in-chief of the award-winning L.A. CityBeat. As a writer and photographer, he’s covered riots, political conventions and a whole lot of pop culture for a variety of publications including Rolling Stone, GQ, Entertainment Weekly, TV Guide and LA Weekly.

Capital & Main is an award-winning online publication that reports from California on the most pressing economic, environmental and social issues of our time. Our mission is to expose threats to the public interest and advance progressive ideas and policies in the nation’s most populous state and one of the world’s most influential centers of commerce, culture and technology.

Spread the word