FOR MOST OF modern history, the easiest way to block the spread of an idea was to keep it from being mechanically disseminated. Shutter the newspaper, pressure the broadcast chief, install an official censor at the publishing house. Or, if push came to shove, hold a loaded gun to the announcer’s head.

This actually happened once in Turkey. It was the spring of 1960, and a group of military officers had just seized control of the government and the national media, imposing an information blackout to suppress the coordination of any threats to their coup. But inconveniently for the conspirators, a highly anticipated soccer game between Turkey and Scotland was scheduled to take place in the capital two weeks after their takeover. Matches like this were broadcast live on national radio, with an announcer calling the game, play by play. People all across Turkey would huddle around their sets, cheering on the national team.

Canceling the match was too risky for the junta; doing so might incite a protest. But what if the announcer said something political on live radio? A single remark could tip the country into chaos. So the officers came up with the obvious solution: They kept several guns trained on the announcer for the entire 2 hours and 45 minutes of the live broadcast.

It was still a risk, but a managed one. After all, there was only one announcer to threaten: a single bottleneck to control of the airwaves.

Variations on this general playbook for censorship—find the right choke point, then squeeze—were once the norm all around the world. That’s because, until recently, broadcasting and publishing were difficult and expensive affairs, their infrastructures riddled with bottlenecks and concentrated in a few hands.

But today that playbook is all but obsolete. Whose throat do you squeeze when anyone can set up a Twitter account in seconds, and when almost any event is recorded by smartphone-wielding members of the public? When protests broke out in Ferguson, Missouri, in August 2014, a single livestreamer named Mustafa Hussein reportedly garnered an audience comparable in size to CNN’s for a short while. If a Bosnian Croat war criminal drinks poison in a courtroom, all of Twitter knows about it in minutes.

In today’s networked environment, when anyone can broadcast live or post their thoughts to a social network, it would seem that censorship ought to be impossible. This should be the golden age of free speech.

And sure, it is a golden age of free speech—if you can believe your lying eyes. Is that footage you’re watching real? Was it really filmed where and when it says it was? Is it being shared by alt-right trolls or a swarm of Russian bots? Was it maybe even generated with the help of artificial intelligence? (Yes, there are systems that can create increasingly convincing fake videos.)

Or let’s say you were the one who posted that video. If so, is anyone even watching it? Or has it been lost in a sea of posts from hundreds of millions of content producers? Does it play well with Facebook’s algorithm? Is YouTube recommending it?

Maybe you’re lucky and you’ve hit a jackpot in today’s algorithmic public sphere: an audience that either loves you or hates you. Is your post racking up the likes and shares? Or is it raking in a different kind of “engagement”: Have you received thousands of messages, mentions, notifications, and emails threatening and mocking you? Have you been doxed for your trouble? Have invisible, angry hordes ordered 100 pizzas to your house? Did they call in a SWAT team—men in black arriving, guns drawn, in the middle of dinner?

Standing there, your hands over your head, you may feel like you’ve run afoul of the awesome power of the state for speaking your mind. But really you just pissed off 4chan. Or entertained them. Either way, congratulations: You’ve found an audience.

HERE’S HOW THIS golden age of speech actually works: In the 21st century, the capacity to spread ideas and reach an audience is no longer limited by access to expensive, centralized broadcasting infrastructure. It’s limited instead by one’s ability to garner and distribute attention. And right now, the flow of the world’s attention is structured, to a vast and overwhelming degree, by just a few digital platforms: Facebook, Google (which owns YouTube), and, to a lesser extent, Twitter.

These companies—which love to hold themselves up as monuments of free expression—have attained a scale unlike anything the world has ever seen; they’ve come to dominate media distribution, and they increasingly stand in for the public sphere itself. But at their core, their business is mundane: They’re ad brokers. To virtually anyone who wants to pay them, they sell the capacity to precisely target our eyeballs. They use massive surveillance of our behavior, online and off, to generate increasingly accurate, automated predictions of what advertisements we are most susceptible to and what content will keep us clicking, tapping, and scrolling down a bottomless feed.

So what does this algorithmic public sphere tend to feed us? In tech parlance, Facebook and YouTube are “optimized for engagement,” which their defenders will tell you means that they’re just giving us what we want. But there’s nothing natural or inevitable about the specific ways that Facebook and YouTube corral our attention. The patterns, by now, are well known. As Buzzfeed famously reported in November 2016, “top fake election news stories generated more total engagement on Facebook than top election stories from 19 major news outlets combined.”

Humans are a social species, equipped with few defenses against the natural world beyond our ability to acquire knowledge and stay in groups that work together. We are particularly susceptible to glimmers of novelty, messages of affirmation and belonging, and messages of outrage toward perceived enemies. These kinds of messages are to human community what salt, sugar, and fat are to the human appetite. And Facebook gorges us on them—in what the company’s first president, Sean Parker, recently called “a social-validation feedback loop.”

There are, moreover, no nutritional labels in this cafeteria. For Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter, all speech—whether it’s a breaking news story, a saccharine animal video, an anti-Semitic meme, or a clever advertisement for razors—is but “content,” each post just another slice of pie on the carousel. A personal post looks almost the same as an ad, which looks very similar to a New York Times article, which has much the same visual feel as a fake newspaper created in an afternoon.

What’s more, all this online speech is no longer public in any traditional sense. Sure, Facebook and Twitter sometimes feel like places where masses of people experience things together simultaneously. But in reality, posts are targeted and delivered privately, screen by screen by screen. Today’s phantom public sphere has been fragmented and submerged into billions of individual capillaries. Yes, mass discourse has become far easier for everyone to participate in—but it has simultaneously become a set of private conversations happening behind your back. Behind everyone’s backs.

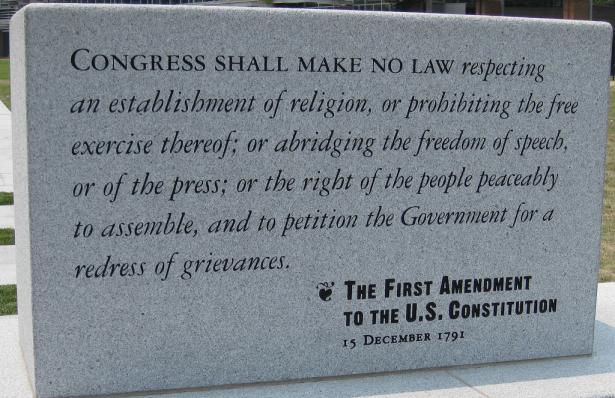

Not to put too fine a point on it, but all of this invalidates much of what we think about free speech—conceptually, legally, and ethically.

The most effective forms of censorship today involve meddling with trust and attention, not muzzling speech itself. As a result, they don’t look much like the old forms of censorship at all. They look like viral or coordinated harassment campaigns, which harness the dynamics of viral outrage to impose an unbearable and disproportionate cost on the act of speaking out. They look like epidemics of disinformation, meant to undercut the credibility of valid information sources. They look like bot-fueled campaigns of trolling and distraction, or piecemeal leaks of hacked materials, meant to swamp the attention of traditional media.

These tactics usually don’t break any laws or set off any First Amendment alarm bells. But they all serve the same purpose that the old forms of censorship did: They are the best available tools to stop ideas from spreading and gaining purchase. They can also make the big platforms a terrible place to interact with other people.

Even when the big platforms themselves suspend or boot someone off their networks for violating “community standards”—an act that doeslook to many people like old-fashioned censorship—it’s not technically an infringement on free speech, even if it is a display of immense platform power. Anyone in the world can still read what the far-right troll Tim “Baked Alaska” Gionet has to say on the internet. What Twitter has denied him, by kicking him off, is attention.

Many more of the most noble old ideas about free speech simply don’t compute in the age of social media. John Stuart Mill’s notion that a “marketplace of ideas” will elevate the truth is flatly belied by the virality of fake news. And the famous American saying that “the best cure for bad speech is more speech”—a paraphrase of Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis—loses all its meaning when speech is at once mass but also nonpublic. How do you respond to what you cannot see? How can you cure the effects of “bad” speech with more speech when you have no means to target the same audience that received the original message?

This is not a call for nostalgia. In the past, marginalized voices had a hard time reaching a mass audience at all. They often never made it past the gatekeepers who put out the evening news, who worked and lived within a few blocks of one another in Manhattan and Washington, DC. The best that dissidents could do, often, was to engineer self-sacrificing public spectacles that those gatekeepers would find hard to ignore—as US civil rights leaders did when they sent schoolchildren out to march on the streets of Birmingham, Alabama, drawing out the most naked forms of Southern police brutality for the cameras.

But back then, every political actor could at least see more or less what everyone else was seeing. Today, even the most powerful elites often cannot effectively convene the right swath of the public to counter viral messages. During the 2016 presidential election, as Joshua Green and Sasha Issenberg reported for Bloomberg, the Trump campaign used so-called dark posts—nonpublic posts targeted at a specific audience—to discourage African Americans from voting in battleground states. The Clinton campaign could scarcely even monitor these messages, let alone directly counter them. Even if Hillary Clinton herself had taken to the evening news, that would not have been a way to reach the affected audience. Because only the Trump campaign and Facebook knew who the audience was.

It’s important to realize that, in using these dark posts, the Trump campaign wasn’t deviantly weaponizing an innocent tool. It was simply using Facebook exactly as it was designed to be used. The campaign did it cheaply, with Facebook staffers assisting right there in the office, as the tech company does for most large advertisers and political campaigns. Who cares where the speech comes from or what it does, as long as people see the ads? The rest is not Facebook’s department.

MARK ZUCKERBERG HOLDS up Facebook’s mission to “connect the world” and “bring the world closer together” as proof of his company’s civic virtue. “In 2016, people had billions of interactions and open discussions on Facebook,” he said proudly in an online video, looking back at the US election. “Candidates had direct channels to communicate with tens of millions of citizens.”

This idea that more speech—more participation, more connection—constitutes the highest, most unalloyed good is a common refrain in the tech industry. But a historian would recognize this belief as a fallacy on its face. Connectivity is not a pony. Facebook doesn’t just connect democracy-loving Egyptian dissidents and fans of the videogame Civilization; it brings together white supremacists, who can now assemble far more effectively. It helps connect the efforts of radical Buddhist monks in Myanmar, who now have much more potent tools for spreading incitement to ethnic cleansing—fueling the fastest- growing refugee crisis in the world.

The freedom of speech is an important democratic value, but it’s not the only one. In the liberal tradition, free speech is usually understood as a vehicle—a necessary condition for achieving certain other societal ideals: for creating a knowledgeable public; for engendering healthy, rational, and informed debate; for holding powerful people and institutions accountable; for keeping communities lively and vibrant. What we are seeing now is that when free speech is treated as an end and not a means, it is all too possible to thwart and distort everything it is supposed to deliver.

Creating a knowledgeable public requires at least some workable signals that distinguish truth from falsehood. Fostering a healthy, rational, and informed debate in a mass society requires mechanisms that elevate opposing viewpoints, preferably their best versions. To be clear, no public sphere has ever fully achieved these ideal conditions—but at least they were ideals to fail from. Today’s engagement algorithms, by contrast, espouse no ideals about a healthy public sphere.

Some scientists predict that within the next few years, the number of children struggling with obesity will surpass the number struggling with hunger. Why? When the human condition was marked by hunger and famine, it made perfect sense to crave condensed calories and salt. Now we live in a food glut environment, and we have few genetic, cultural, or psychological defenses against this novel threat to our health. Similarly, we have few defenses against these novel and potent threats to the ideals of democratic speech, even as we drown in more speech than ever.

The stakes here are not low. In the past, it has taken generations for humans to develop political, cultural, and institutional antibodies to the novelty and upheaval of previous information revolutions. If The Birth of a Nationand Triumph of the Will came out now, they’d flop; but both debuted when film was still in its infancy, and their innovative use of the medium helped fuel the mass revival of the Ku Klux Klan and the rise of Nazism.

By this point, we’ve already seen enough to recognize that the core business model underlying the Big Tech platforms—harvesting attention with a massive surveillance infrastructure to allow for targeted, mostly automated advertising at very large scale—is far too compatible with authoritarianism, propaganda, misinformation, and polarization. The institutional antibodies that humanity has developed to protect against censorship and propaganda thus far—laws, journalistic codes of ethics, independent watchdogs, mass education—all evolved for a world in which choking a few gatekeepers and threatening a few individuals was an effective means to block speech. They are no longer sufficient.

But we don’t have to be resigned to the status quo. Facebook is only 13 years old, Twitter 11, and even Google is but 19. At this moment in the evolution of the auto industry, there were still no seat belts, airbags, emission controls, or mandatory crumple zones. The rules and incentive structures underlying how attention and surveillance work on the internet need to change. But in fairness to Facebook and Google and Twitter, while there’s a lot they could do better, the public outcry demanding that they fix all these problems is fundamentally mistaken. There are few solutions to the problems of digital discourse that don’t involve huge trade-offs—and those are not choices for Mark Zuckerberg alone to make. These are deeply political decisions. In the 20th century, the US passed laws that outlawed lead in paint and gasoline, that defined how much privacy a landlord needs to give his tenants, and that determined how much a phone company can surveil its customers. We can decide how we want to handle digital surveillance, attention-channeling, harassment, data collection, and algorithmic decisionmaking. We just need to start the discussion. Now.

[Zeynep Tufekci is an associate professor at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill at the School of Information and Library Science, and a faculty associate at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University. The Turkish born “techno-sociologist” is also a contributing opinion writer at the New York Times. Her first book, “Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest,” was published by Yale University Press. Find her on Twitter:@zeynep. This article appeared in the February issue of Wired.]

Spread the word