On February 14, the Supreme Court of California declined to review a multimillion-dollar state appeals court ruling against three of this country’s largest paint manufacturers and, predictably, their attorneys immediately pledged to take their case to the U.S. Supreme Court. But, the giant paint companies had already launched a plan to get much quicker relief; they are going to purchase an election.

In a trial that lasted 18 years, three successive California courts agreed with 10 local jurisdictions that the paint manufacturers had knowingly promoted lead based paint, a dangerous product that is responsible for the poisoning of hundreds of thousands of primarily low-income and minority children.

The state supreme court upheld the November 14, 2017 California Sixth District Court of Appeals ruling which largely affirmed the merits of Santa Clara County Superior Court’s landmark $1.15 billion judgment against the companies in 2013. The lower court held the paint companies responsible for assessing and remediating toxic lead based paint from more than four million primarily low-income homes and apartments in 10 California counties and cities.

The court of appeals changed the formula that determines how much the paint companies will be required to pay. But it also unanimously agreed, as stated by Associate Justice Nathan Mihara, that the paint companies knowingly promoted a harmful product long after they were aware “interior residential lead paint posed a serious risk of harm to children.” And further, the appeals court, and later the state supreme court, also affirmed the right to use California’s public nuisance law for redress.

A cynical and brazen initiative

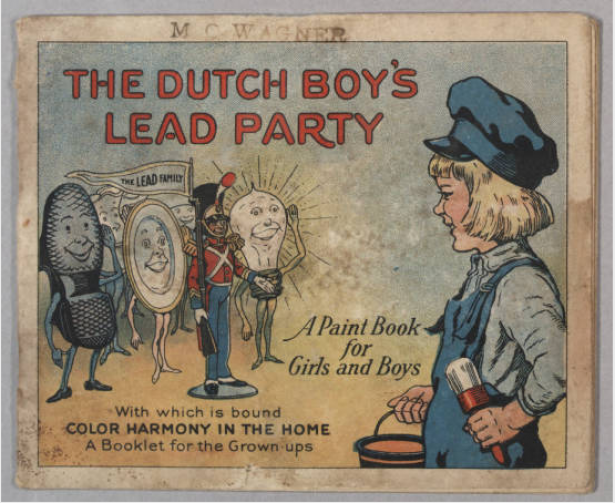

Immediately following that appeals court ruling, the three paint manufacturers launched a statewide ballot initiative, cynically termed The Healthy Homes and Schools Act. And on January 11, 2018, the three companies, ConAgra (Fuller Paint), NL Industries (formerly Dutch Boy), and Sherwin-Williams contributed $2 million dollars each to fund the initiative.

It was the first installment in their campaign to convince California voters to pass a $2 billion bond measure that would effectively shift the court ordered burden of cleaning up the hazardous lead based paint to the state’s residents.

“The initiative is brazen, even by California standards, but also clever,” according to Sacramento Bee columnist Dan Morain, “It would absolve the companies of liability by declaring ‘lead-based paint on or in private or public residential properties, whether considered individually, collectively, or in the aggregate, is not a public nuisance’.” It also would apply to any lawsuit ‘pending on appeal on, or filed after, Nov. 1, 2017,’ rendering the Santa Clara case moot.”

The paint companies will use their initial $6 million war chest to launch a campaign to collect the approximately 370,000 valid signatures required to place the initiative on the statewide November ballot.

They will then have to marshal millions of dollars more to convince the California electorate to vote for a bond initiative, that, according to Greta Hansen, Chief Assistant Counsel for the County of Santa Clara shifts “the burden for their unlawful activities to the taxpayers of the State of California.”

A noxious history

Santa Clara County filed the original lawsuit, the People v. Atlantic Richfield (ARCO) et al, in 2000. The counties of Alameda, Los Angeles, Monterey, San Mateo, Solano, and Ventura soon joined the suit, along with the cities of Oakland, San Diego, and San Francisco.

The suit morphed into the People v. ConAgra, when ARCO and DuPont were dropped from the suit.

On December 16, 2013, following a five week trial, Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge James Kleinberg ruled the paint companies had created a “public nuisance” by continuing to promote interior lead based paint before it was banned by the federal Consumer Products Safety Commission in 1978.

“The defendants sold lead paint with actual and constructive knowledge that it was harmful,” Kleinberg said, citing numerous industry sources. He added, they continued to promote lead-based paint “even when non-leaded paints were available.”

Young children are exceptionally vulnerable to the lead in paint, a serious neurotoxin. There is no safe level of lead in children and even at the lowest levels lead can cause permanent neurological damage to children, decrease IQ and trigger other serious health consequences.

At least 60,000 children, overwhelmingly minority and low-income children, had been identified as lead exposed in the 10 California jurisdictions at the time of the 2013 ruling.

In his Statement of Decision Kleinberg cited numerous industry sources dating back to 1900 to show paint industry awareness of the dangerous health implications of lead based paint.

“SW (Sherwin Williams) had actual knowledge of the hazards associated with lead paint by 1900. In 1900, SW, in its internal publication, Chameleon, told its employees that: ‘It is also familiarly known that white lead is a deadly cumulative poison, while zinc white is innocuous. It is true, therefore, that any paint is poisonous in proportion to the percentage of lead contained in it.’”

Not only did the paint industry continue to promote interior lead based paint, but it also used its lobbying power to forestall any restrictions on the use of lead based paint until 1978.

(Germany, Belgium, France, and Norway had already banned lead paint by the time the International Labor Organization called upon countries to ban or restrict interior lead paint at its White Lead Convention in Geneva in 1921.)

Court documents also provide evidence the paint industry viewed the health dangers of lead and the poisoning of children, primarily minority children, as first and foremost, a public relations problem to be managed.

In a 1956 letter, Manfred Bowditch, Director of Health and Safety for the Lead Industries Association, expressed his frustration over bad publicity and his lack of success in cultivating the “good will” of public health officials.

He wrote, "Aside from the kids that are poisoned (and we still don’t know how many there are), it's a serious problem from the viewpoint of adverse publicity. The basic solution is to get rid of our slums, but even Uncle Sam can't seem to swing that one. Next in importance is to educate the parents, but most of the cases are in Negro and Puerto Rican families, and how does one tackle that job?"

He added, “One can readily understand why, to the operator of a smelter in California or a lead products plant in Texas, the doings of slum children in our eastern cities may seem of little consequence.”

Judge Kleinberg directed ConAgra, NL Industries, and Sherwin-Williams to pay $1.15 billion into a fund to assess, and remove or abate the lead in homes located in the 10 cities and counties.

Kleinberg said, “The court is convinced there are thousands of California children in the jurisdictions whose lives can be improved, if not saved, through a lead abatement plan.”

While the November 2017 court of appeals ruling reduced the number of homes that must be remediated from those built before 1980 to those built before 1950, under the new formula the amount the paint companies will have to pay into the state abatement fund will still be substantial, estimated at upwards of $400 million. There are more than 1.5 million housing units built before 1950 in the California jurisdictions that filed the suit.

A stomach-churning example

Observers believe this is the first time private corporations have attempted to directly use the California initiative process to avoid paying a legal judgment. However, as noted by Los Angeles Times reporter Liam Dillon, “The paint industry has been a major player in statehouses across the country. In 2011 and 2012, Harold Simmons, then owner of NL Industries, donated a total of $750,000 to a political organization supporting Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker and state GOP lawmakers, according to leaked court documents published by the Guardian. Soon after the donations and amid intense lobbying from paint manufacturers, Wisconsin passed legislation to shield the companies from liability in lead paint lawsuits.”

Guardian columnist Lucia Graves wrote in 2016, “The most stomach-churning example in the 1,500 pages is Harold Simmons, the owner of NL Industries – historically a major manufacturer of lead paint. The company faced millions of dollars in lawsuits over alleged lead poisoning of children.

“Simmons gave $750,000 in a series of payments to the third-party group prosecutors suspected of illegally coordinating with the Walker and Republican state senators’ campaigns. The donations came as Walker and state senators were fighting the recall effort, and around the same time the Republican-controlled state senate took steps to pass legislation to effectively grant the industry legal immunity from lead poisoning claims (a federal court later struck the legislation down). To me, that looks like corporate pay-for-play.”

But in California, the courts have repeatedly rejected the paint companies. And, with Democratic majorities in both of California’s legislative houses declaring themselves part of the anti-Trump resistance, it appears the paint companies feel now is not the best time to try to get the legislature to bail them out. So Big Paint is taking the initiative.

More than a little nuisance

Under California’s public nuisance law, judges are allowed to assign liability if it can be proven the defendants were aware their product was creating serious harm to the health of a community at large, not just an individual or a private property. And both the state appeals court and the state supreme court agreed the public nuisance law was appropriately applied in the lead paint case.

This reading of California’s “public nuisance” law distinguishes it from past court decisions in favor of the paint companies in public nuisance lawsuits filed in Rhode Island, New Jersey, Missouri, Illinois, Ohio, and Wisconsin.

Furthermore, the successful lead paint suit, spurred the cities of San Francisco and Oakland to file law suits on behalf of their respective jurisdictions against Chevron, ConocoPhillips, Exxon Mobil, BP and Royal Dutch Shell, which they charge have known for decades that fossil fuel-driven global warming and accelerated sea level rise posed a catastrophic risk to human beings and to public and private property.

The lawsuits ask the courts to hold the defendants jointly and individually liable for creating, contributing to and/or maintaining a public nuisance, and to create an abatement fund for each city to be paid for by defendants to fund infrastructure projects necessary for San Francisco and Oakland to adapt to global warming and sea level rise. The total amount needed for the abatement funds is expected to be in the billions of dollars.

Soon after, another California city and two coastal counties also filed suits against the fossil fuel companies for their role in creating the rising sea levels associated with climate change.

"Like the lead paint case," Vic Sher, a San Francisco attorney representing the city of Imperial Beach and San Mateo and Marin counties in the sea-level cases told the Los Angeles Times’ Michael Hiltzik, "we have an industry that knew its products could inflict serious damage and continued to promote those products anyway."

[Mark Allen, the retired former director of the Alameda County Lead Poisoning Prevention Program, was a key witness for the plaintiffs in the People v. ConAgra case. He is presently a Portside moderator.]

Spread the word