A copy of The Good Soldier Švejk and His Fortunes in the World War—a classic comedy by Jaroslav Hašek, a countryman, contemporary and peer of Franz Kafka—is never far from my desk.

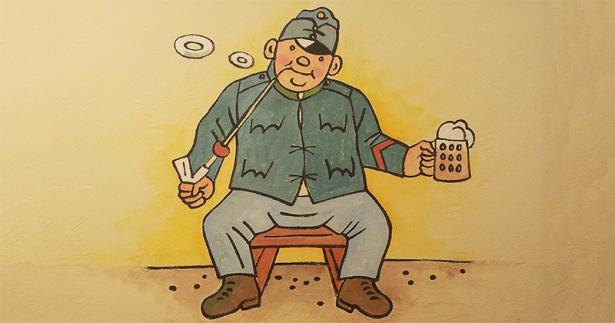

I leaf through it, check out the ditties, drink in the cartoony illustrations, get a bolus of inspiration from a page or two.

Huck Finn defines America. Eugene Onegin defines Russia. Josef Švejk, a professional dog thief and, literally, a certified dimwit who stumbles through World War I, is the quintessential Czech. As it serves up bawdy tales and run-on non-sequiturs, this novel accomplishes much more than to define a nation.

It defines the idiocy of war and the men who wage it, and not just the Great War, but all war. And not just the idiocy of war, but idiocy itself—the big “I.”

Though literally neighbors, Kafka and Hašek take me to very different places. Kafka is about the irreconcilable, the futile. Hašek serves up the idea that dimwittedness—genuine or feigned—is a vaccine against epidemics of madness that grip nations. While Kafka is above considering what-is-to-be-done, Hašek offers an action plan: be a dimwit, or feign being one; there might be a difference between being and pretending, but who the hell cares?

I’ve been returning to this book often since November 2016, refreshing my memories of the good soldier’s ill fortunes, seeking guidance on what is a man to do during this unfortunate time. Many writers have turned to Švejk in dark times past. Joseph Heller did in Catch-22, as did the creators of M*A*S*H, as did Bertolt Brecht. One of his plays transported Švejk into World War II and cast him opposite one Adolf Hitler.

Švejk begins in a Prague drinking establishment called U Kalicha, the chalice. One of the U Kalicha regulars, Švejk steals mutts, docks their tails and ears and applies dyes to alter their appearance so profoundly that they can be sold as exotic canine treasures.

His adventures begin when he engages in an idiotic conversation with an undercover agent of the secret police. Discussion revolves around flies that are leaving droppings upon the portrait of the Emperor Franz Joseph I that graces the wall at U Kalicha.

The story moves on to the secret police headquarters, an insane asylum, the military barracks. There are slow-moving troop-carrying trains, muddy trenches—and folk songs that include this gratuitously offensive pearl of low humor:

The miller and his wife were up by eight

And found these words upon their gate.

“Your daughter, Anne, a maid before,

Is now, alas, a maid no more.”

The most interesting question—then and now—is whether Švejk is genuinely a dimwit. Could it be that he is pretending? Hašek doesn’t answer this question, because he doesn’t wish to. Instead, he lets the novel roll on like the war it describes. The novel concludes with an editor’s note instead of a kicker:

This was the point reached by Jaroslav Hašek in dictating The Good Soldier Švejk and His Fortunes in the World War. He was already ill, and death silenced him forever on 3 January 1923. It prevented him from completing one of the most famous and widely-read novels published after the First World War.

Herein lies this book’s greatest strength. Had Hašek drunk less and lived another 100 years, so would Švejk, for Švejk is literally a book without an end. Left open, it spills into the future.

I propose that political progressives start an annual festival where we would repeat the story of Švejk, prompting every generation to make it their own. Call it the International Švejk Day, but make it truly international, truly secular, truly modern. Since this festival is about Prague, pork would be served to those who crave it. I propose the following four questions: Why do we not become idiots? Why do we not pretend to have become idiots? What do we do about those who have succumbed to idiocy? How do we cling to our sanity as the world descends into madness?

I wish I could ask my mother why she started to read Švejk to me when I was nine and we were living in Moscow. I am not even sure she would have had a clear answer.

Švejk was not banned in the USSR. A novel that depends on the state of mind of the reader, it makes the entire enterprise of book-banning into an insurmountable challenge. That said, the book was age-inappropriate. My classmates were reading novels about young Lenin.

The spirit of the times must have had something to do with my mother’s choice of Švejk. This was 1968. The Czechs, with their experiments in socialism with a human face, were our heroes, our hope. And, of course, there was also something fundamentally satisfying, delightful even, about flies befouling the portraits of emperors.

“Why do we not become idiots? Why do we not pretend to have become idiots? What do we do about those who have succumbed to idiocy? How do we cling to our sanity as the world descends into madness?”

As a child, I had unusual insight into the scene of Švejk’s arrest by secret police. In those days, my parents threatened me with severe punishment in the event I blabbed the things I heard at home, either from my parents or over the short-wave radio, which every nigh delivered the BBC Russian Service, the Voice of America, Radio Liberty and the Voice of Israel. It was a generous menu—you listened to whatever was jammed the least that night.

Emigration was not an option at the time, so, I think that, by default, my mother was preparing me for life in the USSR. Every night, as the short-wave radio was turned off and the latest news from Prague ended, I would get transported to the Austro-Hungarian Empire and follow the anything-but-glorious adventures of men who sang merrily while being as taken to slaughter in a war that made no sense to anyone on any level. It was in Švejk that I first encountered the term “cannon fodder.” It Russian, it’s pushechnoye myaso.

By late August of 1968, a latter-day madness struck in Prague. The mighty USSR—my country—brought tanks into Czechoslovakia. I felt that invasion directly. Those tanks might as well have first passed through our Moscow flat. I was overwhelmed by shame. I kept thinking of the characters as they gather at U Kalicha, looking out to watch our tanks roll.

My parents and I arrived in the US in the Fall of 1973. It took me days to discover a television show called M*A*S*H thay was airing on the CBS network. As soon as I saw M*A*S*H, I recognized that one character, Radar, the company clerk, looked an awful lot like Švejk, especially as depicted by Hašek’s friend, the cartoonist Josef Lada. Hawkeye, the sympathetic, heavy-drinking, skirt-chasing surgeon, was a lot like my mental portrait of another Švejk character, Lt. Lukas, one of the officers whom Švejk served. (Švejk was a batman, with lowercase “B,” an orderly.) Meanwhile, the character of Klinger—the soldier who wears women’s clothes in order to be sent home—would be right at home among Švejk’s band of heroes. (In Švejk, there is actually a soldier who dresses like a girl and goes off to search for his sweetheart. It is he who deflowers the above-mentioned Anne.)

A year or so later, when I picked up a copy of Catch-22, I saw Švejk again. After the election of one Donald Trump, I turned to Brecht, reading everything I could find. I was thus reminded that Brecht had extended the good soldier’s adventures into World War II. You see the same Prague, the same U Kalicha, the same Czech characters, the same enterprise of dog theft, the same beer even, but there is a new threat—the occupying Nazis.

In the final scene, as Brecht suspends reality and Švejk and Hitler meander improbably in the snows outside Stalingrad, the good soldier has this to say to der Führer:

Yes, you cannot go back and you cannot move on

You’re all rotten on top and your bottom is gone

And the east is too cold and the Reds are too red

So I simply don’t know whether to pump you with lead

Or take down my pants and shit on your head.

Brecht’s stage directions here are noteworthy: “Hitler’s desperate thrusts have become a wild dance.”

A wild dance indeed: a fictional character who may or may not be an idiot (it’s irrelevant) is pondering what is to be done about a genuine historical figure who clearly is one. Does a Hitler warrant a volley of lead? Should this volley be real or proverbial? And what is to be made of the turd on the head? Should said turd be corporeal or symbolic? Has more profound a series of questions ever been asked and left unanswered?

Herein lies the power of Švejk. A character in an unfinishable novel, he comes to the rescue again and again, sometimes as himself, sometimes in disguises, and by reminding us who we are, he assists in the monumental task of breathing long enough to crawl out of the shit we are in.

Paul Goldberg’s debut novel The Yid was published in 2016 to widespread acclaim and named a finalist for both the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature and the National Jewish Book Award’s Goldberg Prize for Debut Fiction. As a reporter, Goldberg has written two books about the Soviet human rights movement, and has co-authored (with Otis Brawley) the book How We Do Harm, an expose of the U.S. healthcare system. He is the editor and publisher of The Cancer Letter, a publication focused on the business and politics of cancer. His novel The Chateau is out now from Picador. He lives in Washington, D.C.

Spread the word