On a soundstage in Queens, New York, the crew for Marti Noxon’s new TV series Dietland has built an extremely realistic replica of the offices of a modern women’s magazine. Covers from previous issues decorate the hallway, featuring an array of beautiful young white women and taglines such as “Scarves That Slim.” The kitchen wall, a violent, appetite-diminishing shade of green, is painted with the words try harder. The beauty closet, a serene, cathedral-like space, has floor-to-ceiling shelves labeled dark spot corrector, stretch mark reduction, skin lightener, buffing cream. The products on set seem to number in the thousands.

The only off note is the editor in chief’s office, which looks out onto a backdrop of the New York City skyline and has the requisite pastel tones, velvet upholstery, black-and-white photographs, and Instagrammable bouquets of roses. For the scene Noxon has just filmed, the office was trashed by its occupant, Kitty, played by Julianna Margulies. Chairs are upturned, flowers are strewed everywhere, and magazine pages are in shreds. The aesthetic perfection has been thoroughly dismantled by a woman in a profound state of rage.

Dietland is a show so uncannily timed for its moment, it’s strange to note that Noxon first optioned it two years ago, after listening to the audiobook of Sarai Walker’s 2015 novel of the same name while driving around Los Angeles. In the book, which has been compared to a feminist version of Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club, a guerrilla group of women kidnaps and murders men who’ve been accused of crimes against women, ranging from institutionalized misogyny to violent sexual assault. But that’s just a subplot. The rest of the novel deals with toxic beauty standards, the weight-loss industry, a magazine called Daisy Chain, rape culture, feminist infighting, and the coming of age of a lonely, 300-pound writer named Plum.

Everyone in Hollywood is looking for a Marti Noxon right now.

When Noxon showed an early episode of Dietland to a male friend, he was part impressed, part appalled at how prescient it was. “He kept saying, ‘Did you know? All this was coming?’ ” she says, standing amid the wreckage of Kitty’s office. He was alluding to the past year’s explosive allegations about abusive men in the entertainment industry. “Of course I didn’t.” She shrugs. “But I’ve been alive.”

At 53, Noxon has written, produced, and directed TV shows and films for more than two decades, but it’s only now, right now, that the stories she’s really interested in are stories that Hollywood wants to tell. Jason Blum—one of her producing partners on another upcoming series, Sharp Objects, and a veteran behind movies including Get Out and Whiplash—says that Noxon isn’t doing anything different now than she’s done her whole career. “But the culture caught up with her.” Everyone in Hollywood, he says, is “looking for a Marti Noxon right now.”

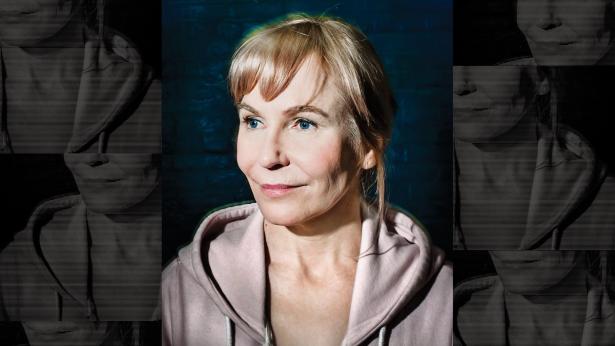

Which is strange, because Noxon herself is the first to admit that she’s something of an oddity. Tiny, blond, with pink lowlights and the maternal, supportive air of a guidance counselor, she’s drawn to gory, violent tales of self-harm, addiction, darkness. Joss Whedon, the creator of the cult hit Buffy the Vampire Slayer—which Noxon worked on as a writer and producer for six seasons, until the series’ finale in 2003—dubbed her the “chains-and-pain gal.” Gillian Flynn, who wrote the novel Sharp Objects (from which the show was adapted), describes Noxon as an “amazing force wrapped in this kind of calm, pleasant package, but also, don’t fuck with her.”

The past two decades have seen an unparalleled explosion of creativity in TV, beginning with The Sopranos and The Wire, running through Breaking Bad andMad Men, and ending up with the zillions of shows currently being made for streaming networks and premium cable. The writer Brett Martin has argued, correctly, that in its recent golden age, the television drama became “the signature American art form of the first decade of the twenty-first century.” But the title of Martin’s 2013 book, Difficult Men, hints at the inequity of the revolution. In prestige TV, men could be adulterers, drug dealers, murderers, gangsters, even serial killers, and still be sympathetic anchors for popular dramas. But the same wasn’t true for women, until recently.

“The TV world has been packed with antiheroes forever,” Flynn says. “Look at Sopranos, look at Breaking Bad. No one ever questions, ‘Are those men likable?’ Finally, in TV now, we’re getting to the same place for women. It doesn’t matter if they’re likable. Are they interesting?”

If a singular thread runs through Noxon’s work, it’s the assertion that women can be just as complex as men—that they can make catastrophic decisions, put themselves in danger, damage others, and (more frequently) damage themselves. And that on-screen, these stories are no less compelling, no less illuminating, than tales of difficult men making meth or metaphorically tumbling from Madison Avenue skyscrapers. The past few years have seen more and more female creators bringing complex women to the small screen. Angry women are at a premium now, their darkest, most humiliating moments having been so publicly unearthed and exposed in one form or another. There’s just so much to be angry about.

It feels like a sign of the times that Noxon has not one but two shows debuting this summer: Dietland arrives on AMC June 4, and HBO will air Sharp Objects, which stars Amy Adams as an alcoholic journalist reporting on a series of murders in her hometown, beginning in July. If Sharp Objects is the latest entry in Noxon’s recent line of work exploring the female capacity for self-destruction, Dietland is something new. She calls it “the fight-back part. The define-yourself-outside-of-the-system part. To change yourself to change the world.”

On set, Noxon is observing a scene from Dietland in which Plum has temporarily moved into a kind of women’s commune in a Manhattan brownstone, founded by the enigmatic heiress to a weight-loss empire. In one of the house’s subterranean white bedrooms (“I wanted to make it feel kind of monastic,” Noxon says), Plum is talking with an artist named Sana, who’s working on a large-scale mosaic of her own face, which is disfigured on one side by shocking burns. Sana explains that she’s come to think of her face as a truth serum, something that lets her see what people are really like. If they can get past it, then they’re essentially decent. If they can’t, she says, “then they have to live with their ugliness. I don’t.”

The dialogue is a characteristic Noxonian mix of quippy and intense. But the subject is a profound one, especially for a basic-cable series. Television right now, Noxon notes, has more of an appetite for stories and characters that are still a hard sell for film.

On the small screen, which is saturated with more original content than ever before (Netflix alone has set its goal at about 700 original series and films in 2018), shows have to work harder to stand out—they have to be a little strange or shocking. Even for Noxon, the pace at which things are changing in television can feel disorienting. She says she looks at Dietland sometimes and thinks, Will this be too tame by the time it airs?

That seems unlikely. Five years ago, when she sold her series Girlfriends’ Guide to Divorce to Bravo, some executives thought putting the word divorce in the title was risky. When Noxon wrote menopause plots into the show, the network discouraged her from using the word or spending too much time on the subject. She wrote the plots anyway. Girlfriends’ Guide was sneakily transgressive, chipping at the edges of what could and couldn’t be shown in a prime-time television series. Dietland, by contrast, is a grenade with the pin pulled out.

In the book, Plum makes a living by answering letters to Kitty, Daisy Chain’s glamorous editor, from confused teenage girls all over the country who idolize her. “Dear Kitty,” one begins. “This is going to sound strange, but I like to cut my breasts with a razor.” Girls write to Kitty about boyfriend troubles and abusive parents, but mostly they write about hating themselves. About feeling hopelessly inadequate. About looking at the bodies of women in Daisy Chain or in online pornography, and feeling grotesque by comparison.

These are impulses Noxon understands. From age 14 through college, she suffered from such severe anorexia that at one point she weighed 69 pounds. In Noxon’s early 20s her anorexia turned into bulimia and then alcoholism, which liberated her from some of the obsessive self-control of her eating disorders but came, she thinks, from a similar desire to numb herself. “It took me years to have an epiphany and find recovery,” she says. “I just started fighting.”

Noxon was born and raised in Los Angeles. Her father was a documentary filmmaker for National Geographic, and her maternal grandfather was one of the first professors to teach film studies. “We have a lot of things in our blood: film, and alcoholism, and anxiety,” she says. “It’s the perfect combination for creatives, if you can survive it.” Her parents split up when she was 8. Her mother, whom she describes as a “pretty dedicated hippie,” eventually came out as a lesbian, and converted to a sect of Buddhism that Noxon likens to a cult. Later in life, her mother was diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

In To the Bone, the 2017 movie that Noxon wrote and directed based on her own experiences with anorexia, she examines her relationship with her mother through the characters of 20-year-old Ellen (Lily Collins) and Ellen’s mother, Judy (Lili Taylor). The film is filled with scenes so outlandish, Noxon could only have taken them from her own life. In one, Judy tries to heal Ellen by feeding her rice milk from a bottle, while holding her like a baby, in a moment that’s both touching and uncomfortable to watch.

Noxon got sober when she was 24 and spent the next few years languishing on the fringes of the entertainment industry. She waitressed during this time, and became friendly with a regular customer, the producer and director Rick Rosenthal. One day, after they had a conversation about a script he had been reading over lunch, he invited her to come to his office and pitch him some ideas. He soon hired her as a development executive, before she even knew what that title meant. For the next few years, she worked for Rosenthal and for the TV writer Barbara Hall, who created the shows Judging Amy and Madam Secretary. Then, in 1997, when Noxon was 32, Joss Whedon hired her to write for Season 2 of Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

Buffy was where Noxon found her voice. The show—which centered on the titular vampire-fighting teenager (and later 20-something)—was so unusual, so groundbreaking, that 15 years after it went off the air, scholars are still debating its significance. The most subversive thing about it was its very concept: that a blond cheerleader could also be the only person capable of saving the world.

“We knew we were getting away with something,” Noxon says. Whedon, Buffy’s creator, had the Wesleyan street cred to enchant the WB network, which was looking for more auteur-driven stories. Still, it was surprising how efficiently he was able to turn a teenage genre series into a smart, provocative story about female power.

For Buffy’s sixth season, Noxon was promoted to executive producer. The show became bleaker, exploring the aftermath of Buffy’s death and her deep unhappiness that her friends used magic to resurrect her. Feeling adrift and depressed, she engages in risky, self-destructive behavior. Many fans, and even Sarah Michelle Gellar—who starred as Buffy—rejected the departure from the breezier mood of past seasons.

But in the years since the season aired, it’s been reassessed. Some critics have compared the primary villains—three isolated nerds who embark on a mission to destroy Buffy—to early avatars of today’s internet trolls. Buffy’s own struggles preceded the darker stories about women that have emerged in recent years, in shows including Jessica Jones, Fleabag, Insecure, Big Little Lies, Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, and UnREAL—an Emmy-nominated series, co-created by Noxon, that makes its own meta-commentary on the portrayal of women in entertainment.

At the time, Noxon found the criticism hurtful. But she had a revelation when she looked at the writers and filmmakers she admired most, the people making the most-interesting art, and considered the various reactions to their work over the years. She realized that if she was going to keep working in Hollywood, she was going to have to tolerate making people angry and getting bad reviews. She figured it would be worth it in the end.

Noxon’s Twitter profile still alludes to the controversy: “I ruined Buffy,” it says, “and I will RUIN YOU TOO.”

Until Noxon left Buffy, a show she describes as “this little enclave of feminist thought and respect for female voices,” she didn’t fully realize how male-dominated the TV industry was. The end of Buffy, she says, was “like being thrown from a moving car at 60 miles per hour.” She wrote for a couple of shows for Fox, then in 2005 moved to ABC, where she wrote for Shondaland, the production company of the TV powerhouse Shonda Rhimes. Noxon had a pathway for success laid out for her there, but she wasn’t happy. “On Grey’s,” she says, “we were doing 22 or 24 [episodes each season] and it was like, ‘Well, I guess they’re gonna have sex again.’ ” She’d met Matthew Weiner, the creator of Mad Men, on a writers’ strike picket line, and after she quit her deal with ABC, Weiner asked her to work on his show.

Her stint on Mad Men lasted two seasons, and she describes it as “the best writing class I never had.” Weiner, she says, “was one of this generation of writers that had a certain rigor about writing that wasn’t formulaic. He could be so searing and funny, but also maintain this tone.” Having come from the frenetic energy of network television, she was relieved to be allowed to write scenes that lasted more than two pages.

Late in 2017, a former writer on Mad Men, Kater Gordon, accused Weiner of sexual harassment, claiming that Weiner, her boss, had told her she owed it to him to let him see her naked. In a series of tweets, Noxon affirmed Gordon’s account, saying she remembered how “shaken and subdued” Gordon had been the following day, and from then on. Weiner, she wrote, was many things, “devilishly clever and witty, but he is also, in the words of one of his colleagues, an ‘emotional terrorist’ who will badger, seduce and even tantrum in an attempt to get his needs met.” (Weiner has denied Gordon’s allegations.)

Noxon says she debated whether or not to speak out. “I knew stuff,” she says, “and I knew it might have a cost to me personally” to come forward. Like everyone in Hollywood, she’s heard stories that haven’t been told yet about other people in the industry, because the fear of offending them is too powerful. But she didn’t want to be one among the sizable group looking the other way to protect their own career.

This is why Plum’s story appeals to her—it’s about a woman who’s lived her whole life in a profound state of fear, who finally reaches a breaking point and decides to make a change. It’s hard not to see Dietland as an allegory for what’s happening with the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements. Noxon is on the fence about how much women in Hollywood should expect from this particular moment, though. “If this was really a reckoning,” she says, “it wouldn’t mean that just a few guys have lost their jobs. But I also understand that you can’t tear the whole thing down.”

After she left Mad Men, in 2009, Noxon bounced between a handful of TV series and films. It was around this time that something began to change for women on television. Homeland, which stars Claire Danes as a CIA operative with bipolar disorder, premiered in 2011. Lena Dunham’s Girls debuted on HBO in 2012. Then came Netflix’s Orange Is the New Black, a dramedy set in a women’s prison, which was created by Jenji Kohan, who happens to be married to Noxon’s brother. In Orange, Kohan used the story of a wealthy white woman sent to prison as the deal sweetener (in an NPR interview she described it as a “Trojan horse”) for the real focus of her show: women on the margins of society, particularly women of color.

Noxon also credits Kohan’s Showtime series, Weeds (2005–12), which starred Mary-Louise Parker as a single mother who becomes a pot dealer, as a show that kicked doors down for female protagonists. “When I had written 10 or 11 pilots and couldn’t get anything made, I would remember that Weeds was 13th,” she says. “I would think, Thirteen, man. At least get to 13 before you give up.”

The morning after filming Plum and Sana’s Dietland scene, Noxon is having breakfast at the NoMad Hotel in Manhattan, eating scrambled eggs with ketchup and trying to conceive of what a more equal entertainment industry—and a more equal world—might look like. For everything she’s accomplished recently, she feels both a sense of pride and an awareness that the hierarchy of power is still fundamentally screwed up, even inside her own head.

That instinct to question everything, to think about the way the world is and should be, is what makes her work so rich, and so provocative. But it doesn’t always make for an easy life. In 2016, she wrote an op-ed for Newsweek in which she grappled with Donald Trump’s misogyny and confessed that she’d twice been sexually assaulted, once by a co-worker and once by someone else’s boyfriend. Then, around the election, Noxon says, she started getting interested in “murder stories.” She sees them as a bridge “between exploring my own dark places and finally wanting to get justice for the fact that at 50-whatever, I’m still having to work this shit out. I really thought I was going to graduate from therapy … but that didn’t happen, so I think maybe I transferred to an angrier phase.”

Camille, the main character in Sharp Objects, is a classic Noxonian lead, in that she struggles with addiction, has a deeply troubled relationship with her mother, and absorbs all her fear and anger, expressing them through words that she has physically carved onto her own body. Camille works at a small newspaper and is assigned to cover a missing-person case in her hometown of Wind Gap, Missouri. While confronting the elements in her own past that have left her so traumatized, Camille discovers that someone in the small town is killing young girls.

After reading the book, Noxon says, she couldn’t shake Camille as a character, and the ways in which she takes the pain in her life and turns it inward. Jason Blum had been struggling to turn the novel into a movie. Noxon persuaded him to let her adapt it for television instead. “Movies are plot-driven; TV, like books, is character-driven,” Blum says. As soon as Noxon proposed making Sharp Objects into a TV show, “it was like the shackles on the storytelling fell off.”

Gillian Flynn, who describes Camille as the manifestation of all of her own personal demons, says she relished the opportunity to work with someone who understood the dimensions of female violence, female sexuality, female anger: “It’s a relief, with Marti, that you don’t have to preface it with anything—say, ‘As a woman …’ ”

Sharp Objects, Noxon says, is about someone who not only survives, but lives to see the truth come out. “I relate to her not wanting to know certain things and having to reckon with them. Because how many people get the true story? The comeuppance for the bad guys in the end?” It’s a similar kind of evolution to the one that Hollywood is currently undergoing, with reverberations across other industries and in other countries. What happens after the truth comes out?

This article appears in the June 2018 print edition with the headline “The Revolution Will Be Televised.”

Spread the word