Democratic enthusiasm and a GOP malaise surrounding President Trump have set the stage for a potentially devastating midterm election for the House Republican majority.

In a series of special elections mostly in reliably GOP districts, Democratic candidates have routinely outperformed Hillary Clinton’s share of the vote from 2016.

At the same time, Republican candidates have underperformed President Trump's vote share in all but two special elections.

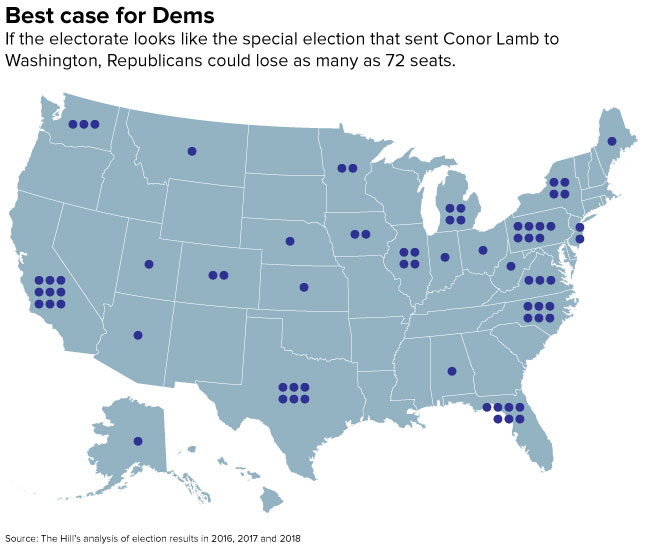

If that pattern holds in November, the worst-case scenario for the GOP is a truly historic wipeout of as many as 72 House seats, according to The Hill’s analysis of special election results and congressional and presidential returns from 2016.

That would mark the deepest decline for either party in a single election cycle since Harry Truman ran against the "Do Nothing Congress" in 1948.

There are a number of reasons why the GOP's worst-case scenario is unlikely to come to pass.

Turnout in November is likely to be higher, which could help the GOP. Republicans noted that Democratic voters in special election districts were far more likely to know when the elections would occur than Republican voters, a sign of Democratic enthusiasm.

Republicans, who have spent far more freely on special elections this year than have Democrats, will face a more even financial playing field.

And some candidates will inevitably run stronger, or weaker, than those who have run in the special elections this year.

Still, the special election results show a consistent pattern that is ominous for Republicans, confirming an enthusiasm gap that shows up in public and private polling.

In seven of eight relevant special elections held over the past 18 months, the Republican candidate has underperformed President Trump’s 2016 share of the electorate. In all eight, the Democratic candidate has outperformed Clinton’s vote share.

(Two special elections were excluded from the analysis: California’s 34th District, which featured a runoff between two Democrats, and Utah’s 3rd District, which gave a third-party presidential contender such a large share of the vote in 2016 as to make comparisons impossible.)

In some cases, the combined difference in performance is relatively small.

In Georgia’s 6th District, Rep. Karen Handel (R) outperformed Trump by 3.5 percentage points, while well-funded Democrat Jon Ossoff outperformed Clinton by 1.4 points. That wasn’t enough, and Handel won the race.

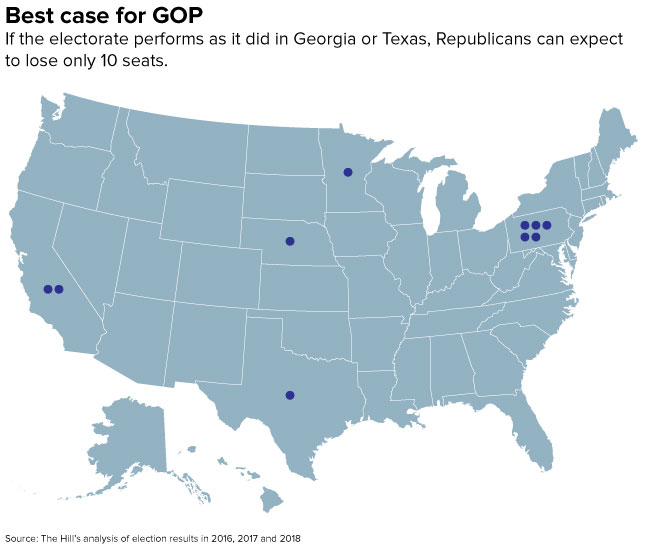

In a multi-candidate Texas special election earlier this summer, Republicans barely underperformed Trump, while Democrats ran close to Clinton’s totals.

If enough races in the fall stick to those patterns, the GOP is likely to retain its majority and lose only 10 seats or so.

But in other special elections, Democratic candidates did dramatically better than Clinton.

In Pennsylvania’s 18th District, Rep. Conor Lamb (D) pulled off an upset in a deeply Republican district, outrunning Clinton by more than 11 points. At the same time, Lamb’s GOP opponent underperformed Trump’s 2016 numbers by 8 percent.

Nearly identical numbers played out in Kansas’s 4th District, where Rep. Ron Estes (R) barely held off a Democratic challenger in a district that gave Trump 60 percent of its vote in 2016.

If those 20-point swings are duplicated across the country, Republicans would stand to lose 72 seats in November.

That scenario, the worst possible case for Republicans based on special election results, would have Democrats picking up seats that are not even on the radar this year.

“Ever since the election, the growing unrest in the Democratic Party has been huge,” said David Smith, a political scientist at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi who has studied special election results. “Those Democrats that have come close [in special elections], those have been strong Republican seats.”

Districts held by Reps. Joe Barton, Michael McCaul and Pete Olson, all Texas Republicans, and such ostensibly safe members as GOP Reps. Steve Chabot (Ohio), Doug LaMalfa (Calif.) and Ted Yoho (Fla.) would all be at risk if Republicans across the board underperform Trump by 8 points, while Democrats outperform Clinton by 11 points.

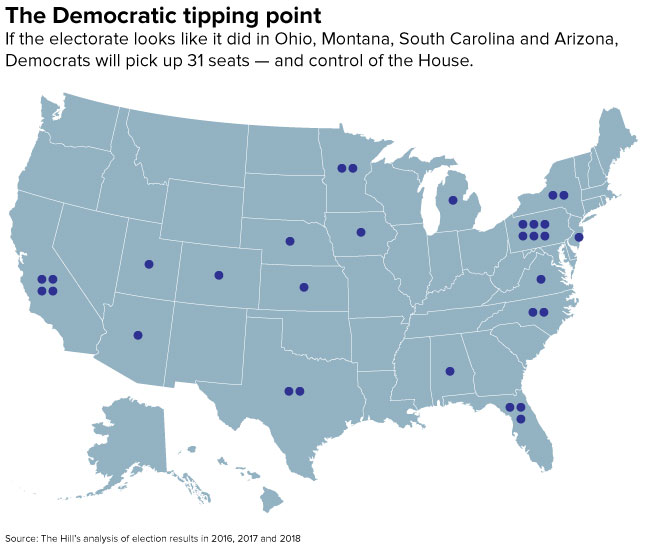

A more likely scenario, one that falls in line with private and public predictions in both parties, is somewhere in the middle — an electorate that looks more like special elections that have occurred in Ohio’s 12th District, Montana’s at-large seat, South Carolina’s 5th District and Arizona’s 8th District.

In all four of those elections, held in districts President Trump won by double digits, the Republican candidate held on to win, but by margins of 1 to 6 percentage points, a far slimmer margin than the Republican candidate who won reelection in 2016.

Under that scenario, Republicans would lose 31 House seats — enough for Democrats to gain control, but by only a slim eight-seat margin. That would be in line with Republican losses in 2006 and 1964, and slightly less severe than the 48 seats Republicans lost in the aftermath of the Watergate scandal in 1974.

Republican strategists brushed off the special election results as unique to the moment, one-off contests that cannot adequately gauge where either party stands before November.

“We believe special elections aren’t necessarily indicative of either party’s fate in the fall. However, we’re going to wake up every day and work like we’re 10 points down,” said Matt Gorman, a spokesman for the National Republican Congressional Committee (NRCC).

Tom Davis, the former NRCC chairman, said elections in which the political battleground is unusually large tend to benefit the party that does not control the White House in two ways: First, the out party tends to over-perform in open seats; 37 Republicans have opted not to run for reelection to their current seats this year. And second, members of the majority who have not faced a competitive race in years can get caught napping.

“For second-tier Republicans who have spent their careers running against Obama, you’re going to get some surprises,” Davis said.

Courtney Alexander, a spokeswoman for the Republican-backing Congressional Leadership Fund, said the special election results show that no one can take their election for granted.

“The biggest takeaway from a lot of these specials is that candidates and campaigns matter, and it is going to be important for candidates to be able to define both themselves and their opponents and talk to voters and give voters a reason to go out and vote for them,” Alexander said.

In the past century, special election results have often hinted at a party’s performance in the subsequent general election, said Eric Ostermeier, a political scientist at the University of Minnesota and the author of the Smart Politics blog. Republicans notched big gains in 1942, 1946, 1952, 1978 and 1994 after winning a handful of Democratic-held seats in early specials.

Democratic wins in Republican-held seats in 1954, 1970, 1974 and 2008 similarly presaged a blue wave the following November.

Those results “suggest when we see only one party flipping multiple U.S. House seats in specials, that party tends to have a good midterm,” Ostermeier said. “Democrats didn’t quite do that this cycle, flipping just one seat, but gained significant enough ground in many of these other GOP-friendly districts to justify their optimism.”

Spread the word