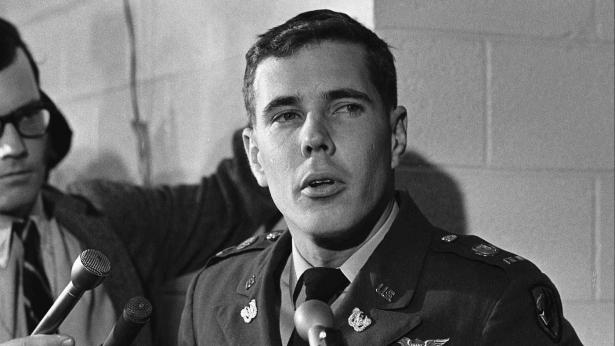

Everybody's heard of the My Lai massacre — March 16, 1968, 50 years ago today — but not many know about the man who stopped it: Hugh Thompson, an Army helicopter pilot. When he arrived, American soldiers had already killed 504 Vietnamese civilians (that's the Vietnamese count; the U.S. Army said 347). They were going to kill more, but they didn't — because of what Thompson did.

I met Thompson in 2000 and interviewed him for my radio program on KPFK in Los Angeles. He told the story of what happened that day, when he and his two-man crew flew over My Lai, in support of troops who were looking for Viet Cong fighters.

"We started noticing these large numbers of bodies everywhere," he told me, "people on the road dead, wounded. And just sitting there saying, 'God, how'd this happen? What's going on?' And we started thinking what might have happened, but you didn't want to accept that thought — because if you accepted it, that means your own fellow Americans, people you were there to protect, were doing something very evil."

Who were the people lying in the roads and in the ditch, wounded and killed?

"They were not combatants. They were old women, old men, children, kids, babies."

Then Thompson and his crew chief, Glenn Andreotta, and his gunner, Lawrence Colburn, "saw some civilians hiding in a bunker, cowering, looking out the door. Saw some advancing Americans coming that way. I just figured it was time to do something, to not let these people get killed. Landed the aircraft in between the Americans and the Vietnamese, told my crew chief and gunner to cover me, got out of the aircraft, went over to the American side."

What happened next was one of the most remarkable events of the entire war, and perhaps unique: Thompson told the American troops that, if they opened fire on the Vietnamese civilians in the bunker, he and his crew would open fire on them.

"You risked your lives," I said, "to protect those Vietnamese civilians."

"Well, it didn't come to that," he replied. "I thank God to this day that everybody did stay cool and nobody opened up. ... It was time to stop it, and I figured, at that point, that was the only way the madness, or whatever you want to call it, could be stopped."

Back at their base he filed a complaint about the killing of civilians that he had witnessed. The Army covered it up. But eventually the journalist Seymour Hersh found out about the massacre, and his report made it worldwide news and a turning point in the war. Afterwards Thompson testified at the trial of Lt. William Calley, the commanding officer during the massacre.

Then came the backlash. Calley had many supporters, who condemned and harassed Thompson. He didn’t have much support — for decades. It took the Army 30 years, but in 1998, they finally acknowledged that Thompson had done something good. They awarded him the Soldier's Medal for “heroism not involving actual conflict with an enemy.”

On the 30th anniversary of the massacre, Thompson went back to My Lai and met some of the people whose lives he had saved. "There were real good highs," he told me, "and very low lows. One of the ladies that we had helped out that day came up to me and asked, 'Why didn't the people who committed these acts come back with you?' And I was just devastated. And then she finished her sentence: she said, 'So we could forgive them.' I'm not man enough to do that. I'm sorry. I wish I was, but I won't lie to anybody. I'm not that much of a man."

And what were the highs?

"I always questioned, in my mind, did anybody know we all aren't like that? Did they know that somebody tried to help? And yes, they did know that. That aspect of it made me feel real good."

Today there's a little museum in My Lai, where Thompson is honored, and which displays a list of the names and ages of people killed that day. Trent Angers, Thompson's biographer and friend, analyzed the list and found about 50 there who were 3 years old or younger. He found 69 between the ages of 4 and 7, and 91 between the ages of 8 and 12.

Nick Turse investigated violence in Vietnam against noncombatants for his book “Kill Anything that Moves.” He concluded — after a decade of research in Pentagon archives and more than 100 interviews with American veterans and Vietnamese survivors — that Americans killing civilians in Vietnam was “pervasive and systematic.” One soldier told him there had been "a My Lai a month."

We know that Americans committed a massacre 50 years ago today; and we also know that an American stopped it. Hugh Thompson died in 2006, when he was only 62. I wish we could have done more to thank him.

[Jon Wiener is professor emeritus of history at UC Irvine, and working, with Mike Davis, on a book on Los Angeles in the 1960s.]

Spread the word