About 20 years ago, an entrepreneur named George Mitchell proved that it was possible to get lots of oil and gas out of parts of the earth long thought to be sucked dry, by injecting liquid at high pressure into a horizontal well below the surface. About 10 years ago, fracking — the common term for this process — began in earnest.

In that short amount of time, fracking in America has turned the energy world upside down. A decade and a half ago, Congress was hand-wringing about impending shortages of oil and natural gas. By the end of 2015, President Barack Obama lifted the ban against oil exports. Today, America is the world’s largest producer of natural gas and is an oil powerhouse, ready to eclipse both Saudi Arabia and Russia.

This has led to muscular claims about American energy wealth. Erik Norland, executive director of CME Group, a derivatives marketplace, calls fracking “one of the top five things reshaping geopolitics.”

This radical change has resulted in widespread concern about the impact of fracking on the environment, about earthquakes and water contamination. But another, less well-known controversy may prove to be more important.

Some of fracking’s biggest skeptics are on Wall Street. They argue that the industry’s financial foundation is unstable: Frackers haven’t proven that they can make money. “The industry has a very bad history of money going into it and never coming out,” says the hedge fund manager Jim Chanos, who founded one of the world’s largest short-selling hedge funds. The 60 biggest exploration and production firms are not generating enough cash from their operations to cover their operating and capital expenses. In aggregate, from mid-2012 to mid-2017, they had negative free cash flow of $9 billion per quarter.

These companies have survived because, despite the skeptics, plenty of people on Wall Street are willing to keep feeding them capital and taking their fees. From 2001 to 2012, Chesapeake Energy, a pioneering fracking firm, sold $16.4 billion of stock and $15.5 billion of debt, and paid Wall Street more than $1.1 billion in fees, according to Thomson Reuters Deals Intelligence. That’s what was public. In less obvious ways, Chesapeake raised at least another $30 billion by selling assets and doing Enron-esque deals in which the company got what were, in effect, loans repaid with future sales of natural gas.

But Chesapeake bled cash. From 2002 to the end of 2012, Chesapeake never managed to report positive free cash flow, before asset sales.

In early 2015, another famous hedge fund manager, David Einhorn, went public with his skepticism at an investment conference. He had looked at the financial statements of 16 publicly traded exploration and production companies and found that from 2006 to 2014, they had spent $80 billion more than they received from selling oil.

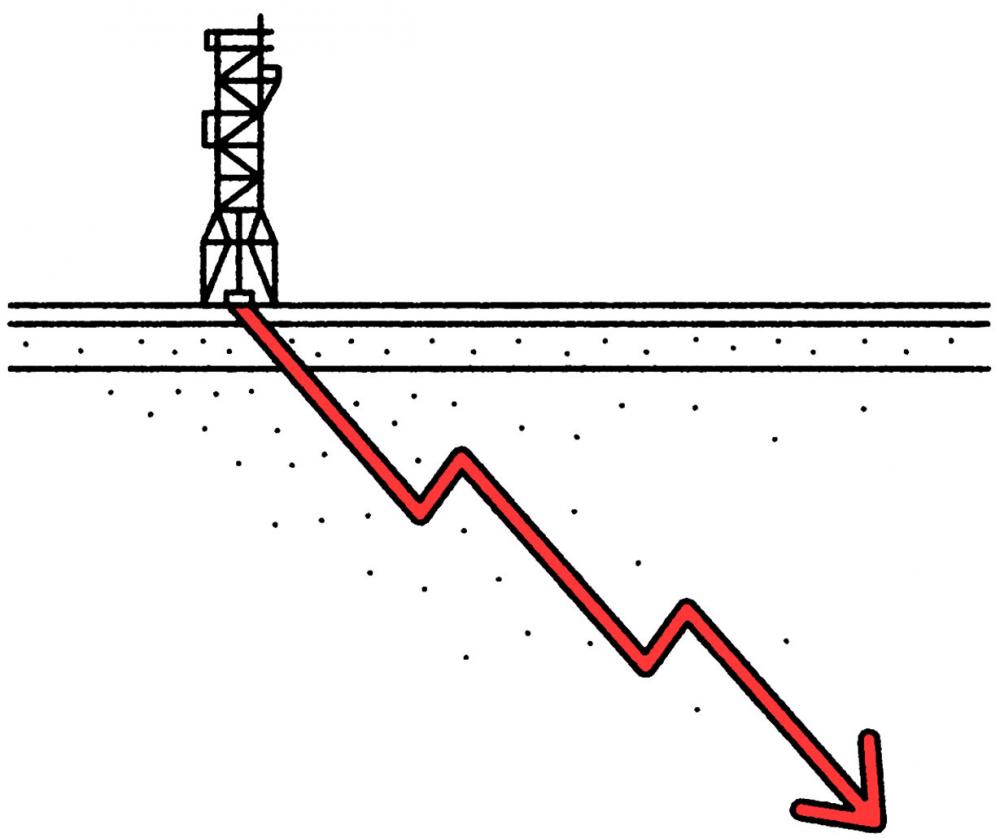

A key reason for the terrible financial results is that fracked oil wells show a steep decline rate: The amount of oil they produce in the second year is drastically smaller than the amount produced in the first year. According to an economist at the Kansas City Federal Reserve, production in the average well in the Bakken — a key area for fracking shale in North Dakota — declines 69 percent in its first year and more than 85 percent in its first three years. A conventional well might decline by 10 percent a year. For fracking operations to keep growing, they need huge investments each year to offset the decline from the previous years’ wells.

Because the industry has such a voracious need for capital, and capital costs money, fracking could not have taken off so dramatically were it not for record low interest rates after the 2008 financial crisis. In other words, the Federal Reserve is responsible for the fracking boom.

Amir Azar, a fellow at the Columbia University Center on Global Energy Policy, calculated that the industry’s net debt in 2015 was $200 billion, a 300 percent increase from 2005. But interest expense increased at half the rate debt did because interest rates kept falling. Dr. Azar recently called the post-2008 era of super-low interest rates the “real catalyst of the shale revolution.”

Zak Tebbal

Fracking is such a fragile industry that it is not hard to make it go bust. Saudi Arabia almost succeeded in doing so in 2014, when oil ministers from OPEC decided that they would not cut production in order to prop up falling oil prices. This was seen as an attempt by the Saudis to kill off shale, by cutting prices below the point where American frackers could afford to produce a barrel. By mid-2016, American oil production had declined by nearly a million barrels a day and some 150 oil and gas companies filed for bankruptcy.

The death of Aubrey McClendon, the former chief executive of Chesapeake, in the spring of 2016 seemed to mark the end of the industry. On March 2, Mr. McClendon died instantly when his car slammed into a concrete bridge on Midwest Boulevard in Oklahoma City. He was speeding, wasn’t wearing a seatbelt and didn’t appear to make any effort to avoid the collision. A day earlier, a federal grand jury had indicted McClendon for violating antitrust laws. (His death was ruled an accident, and prosecutors have since withdrawn the charges, which he denied.)

Mr. McClendon was once listed at No. 134 on the Forbes list of 400 richest Americans, with an estimated net worth of over $3 billion. But because he borrowed so much money and secured business loans with personal guarantees, lawyers were wrangling over claims against his estate two years after his death, including the $465 million loan made by multiple Wall Street firms. Vulture funds descended, buying the debt for less than 50 cents on the dollar, one person who was involved told me.

It wasn’t the end, though. Fracking has been more resilient than anyone, including its proponents, would have dreamed. In its most recent forecast, the Energy Information Administration predicted that United States crude oil production would average almost 10.6 million barrels a day in 2018 and reach 12.1 million barrels a day by 2023.

A big reason for fracking’s resurgence is an area of West Texas and Southeast New Mexico known as the Permian Basin. It wasn’t a secret that there was oil in the Permian, which had its first boom almost a century ago. But oil men thought it was mostly tapped out — until entrepreneurs began to frack there around 2010. Scott Sheffield, the former chief executive of Pioneer Natural Resources, has said that the Permian could hold 75 billion barrels of oil, second only to the Ghawar field in Saudi Arabia.

Believers say that technology will dramatically reduce costs of fracking wells, reshaping the financial firmament so that companies can make money, even with low oil prices. According to a 2016 paper by the board of governors of the Federal Reserve, not only are rigs in the Bakken region drilling more wells, but each well is producing more. Extraction from new wells in the area in their first month of production has roughly tripled since 2008. The break-even cost, the estimate of what it costs to get a barrel of oil out of the ground, has plunged.

The best-run companies, which often focus on the Permian, are now making some money. “Their rates of return are still below levels that will sustain the industry in the long run,” says Brian Horey, who runs Aurelian Management, but “they are trending in the right direction.”

And yet only five of the top 20 fracking companies managed to generate more cash than they spent in the first quarter of 2018. If companies were forced to live within the cash flow they produce, American oil would not be a factor in the rest of the world, an investor told me.

It wasn’t just the rediscovery of the Permian that helped restart the oil boom after plunging prices almost killed it. The most important factor is the one that started the boom in the first place. “It came back because Wall Street was there,” Mr. Chanos told me. In 2017, American frackers raised $60 billion in debt, up almost 30 percent since 2016, according to Dealogic.

Interest rates have remained low, helping debt-laden companies afford their borrowing costs. And pension funds, which need high yields to make payouts to retirees, have turned to hedge funds that invest in high-yield debt, like that of energy firms. They are also investing with private equity firms which, in turn, have shoveled money into shale companies.

Private equity funds dedicated to natural resources raised nearly $70 billion of capital in 2015, according to SailingStone Capital Partners, an energy-focused investment firm, and over $100 billion in 2016. Today, 35 percent of all horizontal drilling (the industry’s preferred terminology) is done by privately backed companies.

Private equity titans have made fortunes, but not necessarily because the companies they fund have produced profits. Private equity firms have generated some of their returns by selling one company to another, or taking a company they’ve funded public.

For a long time, the public markets have been valuing fracking companies not based on a multiple of profits, the standard way of valuing a company, but rather according to a multiple of the acreage a company owns. As long as companies are able to sell stock to the public or sell themselves to companies that are already public, everyone in the chain, from the private equity funders to the executives, can continue making money.

It’s all a bit reminiscent of the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s, when internet companies were valued on the number of eyeballs they attracted, not on the profits they were likely to make. As long as investors were willing to believe that profits were coming, it all worked — until it didn’t.

These days, the rhetoric of “energy independence,” meaning an America that no longer depends on anyone else for its oil, not even Saudi Arabia or OPEC, is in perfect harmony with “Make America Great Again.” But rhetoric doesn’t produce profits, and most things that are economically unsustainable, from money-losing dot-coms to subprime mortgages, eventually come to a bitter end.

Bethany McLean, a contributing editor at Vanity Fair, is the author of “Saudi America: The Truth About Fracking and How It’s Changing the World,” from which this essay is adapted.

Her column, "The Bulldog", appeared regularly in Fortune.

McLean is the co-author, with Fortune colleague Peter Elkind, of The Smartest Guys in the Room, exposing the corrupt business practices of Enron officials. The book was the result of her reporting on Enron for the magazine and she first wrote about Enron with her article in the March 5, 2001 issue of Fortune entitled, "Is Enron Overpriced?". The book was later made into the Academy Award nominated documentary Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room.

She co-authored a book with New York Times columnist Joe Nocera on the 2008 financial crisis titled All the Devils Are Here. It details what happened and concludes it was not an accident, that banks understood the big picture before the crisis happened but continued with bad practices.

In September 2015, she published Shaky Ground: The Strange Saga of the U.S. Mortgage Giants which examines the governance and financial situation of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac seven years after the 2008 financial crisis.

Spread the word