On November 6, voters in the US territory of Guam elected their first female governor, first openly gay lieutenant governor and a 15-person legislature in which 10 senators are women. Guam also elected its first senator of Chuukese descent (an ethnic minority from Chuuk, Micronesia). Another candidate, a transgender woman, wasn’t elected, but had a strong showing in an election that has energized Guam’s progressive community.

“After you’ve had 16 years of Republican governors on Guam, I think people were ready for something different,” said Michael Lujan Bevacqua, an assistant professor at the University of Guam who specializes in Chamoru Studies — the study of Guam’s Indigenous people and culture.

“I think that we are seeing a shift,” he told Truthout. “I doubt it’s irreversible but it’s definitely shifting.”

Now, with eight of 15 candidates having expressed interest in the possibility of independence from the US, Bevacqua said the new legislature “could lead to tangible steps toward a change in political status.”

Guam, which is part of the Mariana Islands in the Western Pacific, has been a US territory since it was acquired in 1898 after the Spanish-American War. But 500 years of colonialism and over a century of US military occupation have left many on Guam hungry for self-determination. The results of this month’s election are, for many on Guam, a glimmer of hope.

Moñeka De Oro, a community organizer with the group Independent Guåhan (a political independence advocacy group whose name means “Independent Guam”), told Truthout she couldn’t be more excited about the results. “To have our first maga’håga, or female governor, 10 out of 15 legislators are female, and a Democratic supermajority is such an empowering change,” De Oro said. “Many of those who won have been openly critical of military expansion in our region, and many have also expressed support of self-determination votes for our island.”

She added, “Now, more than ever, decolonization is possible.” In response to the strong showing of female candidates, De Oro said, “The Indigenous culture of the Marianas is strongly matrilineal, so to return to that tradition after centuries of patriarchy and colonization is just amazing.”

When newly elected officials are sworn in on January 7, they’ll have no shortage of challenges awaiting them. The outgoing Republican governor and his administration leave behind public debt, fiscal problems, and a host of internal controversies and conflicts.

The island of 166,000 is also grappling with multiple issues, including a troubled health care system, homelessness and income inequality. Recent super-typhoons have underscored the region’s vulnerability to climate change, and the perennial questions of the large US military presence on the island and Guam’s political status remain unsolved.

The top vote-getter in Guam’s unicameral legislature was incumbent Sen. Therese Terlaje. The election of a supermajority of progressive and female candidates was no surprise to her. Terlaje described a field of strong leaders with solid backgrounds and long records of advocating on behalf of cultural and historical preservation, the environment and diversity in economic policies.

More than anything else, Terlaje told Truthout, Guam’s people want collaboration to move the community forward. “I was happy that we had senators who were very in tune with the diverse population on Guam in terms of income,” Terlaje said.

Another urgent issue on Guam is providing adequate health care for a community where the public hospital recently lost its accreditation for being out of compliance in multiple procedures. Guam’s residents frequently must travel overseas — California, Hawaii and the Philippines are common destinations — for treatment. What’s more, despite having one of the largest per capita populations of veterans in the nation, Guam has no VA hospital, forcing many vets to travel 3,800 miles to Hawaii for treatment.

Guam’s status as a US colony, Terlaje said, impedes its economic growth and imposes unequal tax policies, reimbursement and restricts Guam’s ability to control how its own land and water can be used to develop a more sustainable economy and combat climate change.

“Because we are the American territory furthest out, we are the land they want,” she said, referring to the US military’s use of Guam and the neighboring Mariana Islands, where it conductions year-round exercises, live-fire training and sonar along with regional partners.

Terlaje sees achieving self-determination an urgent mandate, calling educating the public for a plebiscite “our biggest challenge, our most immediate challenge and one that we can actually accomplish. It’s a goal that we can meet in two years, I think,” expressing confidence that newly elected officials will fulfill promises to make a plebiscite a priority.

Long seen as a way to address Guam’s unresolved political status, a plebiscite would present Guam with three options: statehood, independence or free association, an international legal status that can include elements of political sovereignty, citizenship or the right of residence, and close economic alignment as in the case of New Zealand and the Cook Islands, or the US and the freely associated nations of the Republic of the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia and the Republic of Palau. Guam remains one of the world’s few remaining non-self-governing territories.

Guam’s New Governor-Elect

Guam’s new Governor-elect is Lourdes A. “Lou” Leon Guerrero, a registered nurse and, until recently, president and CEO of the Bank of Guam. Her running mate, Lieutenant Governor-elect Josh Tenorio, told Truthout the pair campaigned on creating unity with the goal of building a Guam that is “fair, safe, compassionate and prosperous,” with an emphasis on public health issues and finance reform.

On questions of Guam’s military role and political status, Tenorio said he “understands and supports the military mission,” but said that “there has to be a balance and there has to be a rationale” to justify development or other actions taken that impact the local community and the environment.

Ten years ago, he said, people would uncritically look at the military presence on Guam’s in terms of economic opportunities. But today, he said Guam’s people want the government and media to hold the military and contractors accountable to ensure their plans are consistent with their promises.

Guam has a complicated relationship with the US military. Serving in the armed forces is, for many on Guam, a family tradition, and the island has among the highest enlistment rates per capita in the nation. Many, especially elders, remain grateful to the US military for driving out Japanese forces after a brutal three-year occupation.

But the return of the Americans also brought land seizures, pollution and expanding militarization. In 2017, North Korea named Guam, which is home to nuclear capable aircraft and a continuous bomber presence mission, as a possible target.

“I always see Guam and Okinawa as bearing a lot of the brunt for decisions that are made by Japan and the United States,” Tenorio said.

Asked if Guam is a US colony, the lieutenant governor-elect didn’t hesitate: “Sure it is … any political grouping outside of the 50 states has to be a colony if decisions are made in a process that our citizenry doesn’t have full participation in.” Guam has one non-voting delegate in the US Congress.

“We’re very conscious of the fact that we don’t get to vote for president,” Tenorio said. “We’re not entitled to the full rights of US citizens living in the 50 states, and it causes people to be very upset.”

According to Tenorio, he and Leon Guerrero have a goal to hold a plebiscite on the future of Guam’s political status within two years, which he said is important because “it rights a longstanding historical injustice.”

Recovering the Past

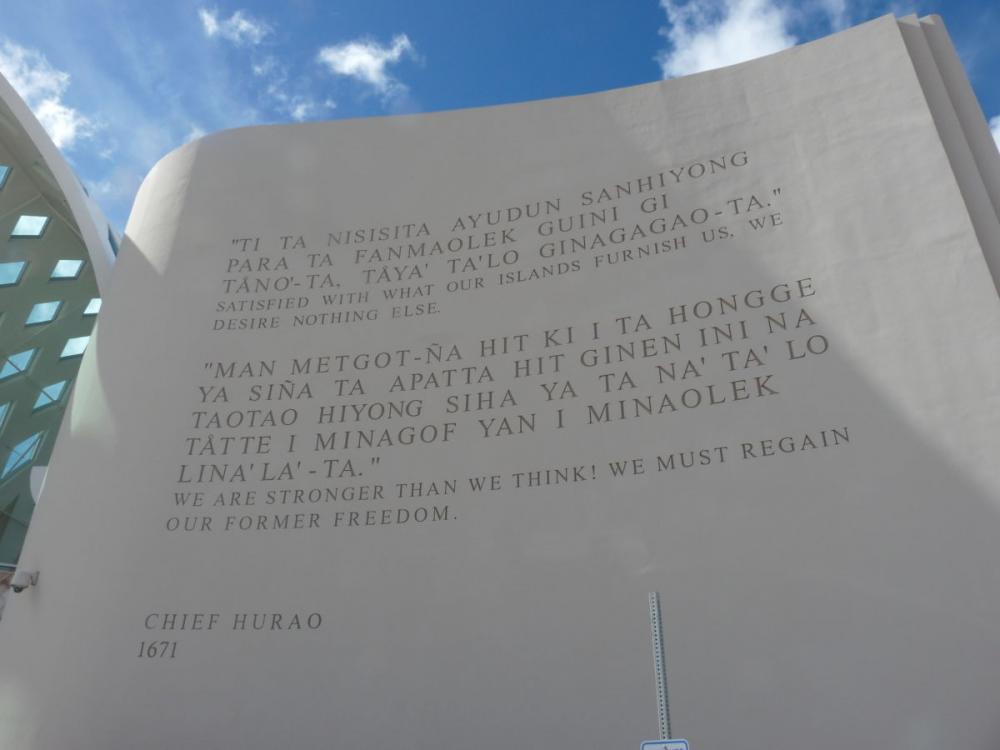

The front entrance to The Guam Museum was designed in the shape of an open book replicating a speech attributed to Maga’låhi (Chief) Hurao. Written in Chamoru and English, part of the text reads, “We are stronger than we think! We must regain our former freedom.” The speech is considered a call-to-consciousness against colonization.

Jon Letman

The people of Guam refer to Governor-elect Leon Guerrero as amaga’håga, the term for an ancient Chamoru social position of power held by a female leader in what was historically a dual male-female clan position. Following colonial periods by first the Spanish and then the US, the male equivalent maga’låhi was adopted to mean “governor,” according to Bevacqua.

Threatened by powerful women leaders, he added, maga’håga were suppressed, first by the Spanish priesthood, and then under US military rulers. Bevacqua called the election of Guam’s first female governor cause for excitement.

“I’m always encouraging people: ‘Don’t celebrate this in the context of American achievement; celebrate this in the context of our own decolonization,'” Bevacqua told Truthout. “The election of our first female executive is an achievement in terms of recovering our past.”

Bevacqua said, “Guam has had a history of strong female leadershipdespite colonial attempts to suppress it. This election manifests the resurgence of that female leadership.”

The Illusion of Inclusion

This fall, Guam and the neighboring Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) were hit hard by tropical cyclones, causing widespread destruction, especially in CNMI.

Guam’s three incoming senators who ran on strong environmental platforms have also been vocal critics of the military buildup. One of those senators is University of Guam history and culture professor Dr. Kelly G. Marsh-Taitano. She spoke of “rapid and intensive militarization” in reference to the planned deployment of some 5,000 US Marines to Guam, in addition to the construction of a new marine base and a live-fire training range which is being built nearby other military installations on northern Guam.

Just days before the election, Marsh-Taitano and 10 other candidates joined some 150 Guam residents to protest the unannounced removal of culturally important cultural resources and bulldozing of a Chamoru heritage site at the location of the new marine base.

On an island where more than one-quarter of the land is occupied by the US military, residents like Marsh-Taitano are concerned about cultural and environmental impacts as the US promises to “reduce the burden” of US troops on Okinawa by transferring Marines to Guam.

A longtime advocate for protecting Guam’s environment and Chamoru culture, Marsh-Taitano described the disconnect many on Guam feel with the US.

“It’s been 120 years that we’ve had a relationship with the United States and yet … we’re still so visibly absent. We’re not on the flag, we’re not on a typical map. We have no real presence in Congress — not any voting presence.” Even Guam’s census statistics are separated from the 50 states.

As a new senator, Marsh-Taitano said she is eager to bolster the community in developing a greater sense of pride despite what she described as a minimization of Guam’s importance by everyone, from members of Congress to US corporate media to public school text books.

The entrance to Guam’s legislature in the capital city of Hagåtña where voters recently elected the island’s first female governor and 10 of 15 incoming senators are women.

Jon Letman

Defining Guam on Guam‘s Terms

Desiree Taimanglo-Ventura, an English and communications professor at Guam Community College, said that the 2009 release of a Department of Defense Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) spurred Guam’s citizens to confront US military presence in a way it hadn’t before, which led the public, community leaders and politicians to also examine the issues more closely.

“It forced us to have hard discussions in a condensed amount of time,” Taimanglo-Ventura said. “The benefit is the community learned a lot and we have more thoughtful conversations now.”

The DEIS, which was more than 10,000 pages long, examined potential challenges and benefits to a proposed military buildup. In response, the US Environmental Protection Agency rated the DEIS “Environmentally Unsatisfactory,” expressing concerns about possible harm from increased population pressures, threats to water resources, wastewater treatment, impacts to more than 71 acres of coral reefs, and other concerns.

Taimanglo-Ventura and other opponents to the current military buildup see further militarization and environmental issues (destruction of forest, pollution, access to land) as inseparable from Guam’s political status and right to self-determination.

“I think what Guam came to realize is that what’s most important to us — our islands, our people, our environment, our land — and regardless of what you are, we wanted to put the people in office who are going to fight for those things,” Taimanglo-Ventura said.

The outcome of this election, with its strong showing by women, has energized many on Guam, but women in leadership roles is nothing new in Chamoru culture.

“Guam has always done a wonderful job of putting women in high-powered positions,” Taimanglo-Ventura said. “We’ve always had women calling the shots here in a lot of ways, and in positions that matter. So yes, it is nice to see a maga’håga, but I think our maga’hågas have always been here.”

Asked about parallels between Guam’s election outcome and the gains made by female candidates in the continental United States, she said, “I think as a colony, Guam is both different and the same. There are parallels, but we have a really unique position. While we can be enthusiastic about Western feminist movements, it’s important to always note that our history as women here has been different and unique. What we need more than Western brand feminism is a return to ourselves.”

Copyright, Truthout. Reprinted with permission. May not be reprinted without permission.

Jon Letman is a freelance journalist on Kauai. He writes about politics, people and the environment in the Asia-Pacific region. Follow him on Twitter: @jonletman.

Since Donald Trump took office, progressive journalism has been under constant attack and companies like Facebook and Google have changed their policies to limit your access to sites like Truthout.The result is that Truthout's articles are reaching fewer people at a time when we need genuinely independent news more than ever. Here’s how you can help: Since Truthout doesn’t run ads or take corporate or government money, we rely on our readers for support.By making a monthly or one-time donation of any amount to Truthout, you’ll help us publish and distribute stories that have a real impact on people’s lives. Click here to make a donation today to Truthout.

Spread the word