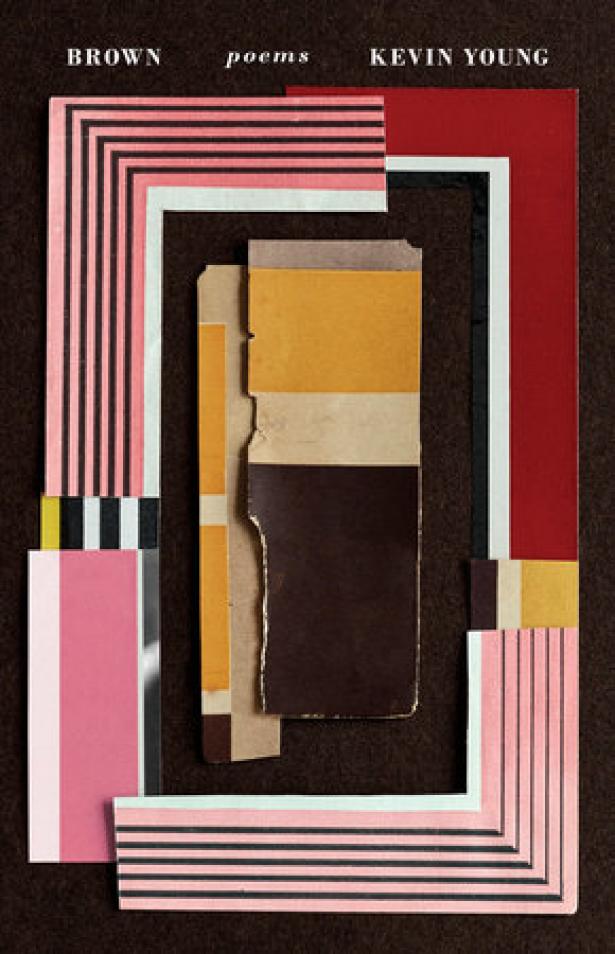

Brown

Poems

Kevin Young

Knopf

ISBN 9781524732547

When I signed up to review Brown: Poems, I had no intimation that Kevin Young, the author of the poems, had lived in Topeka, Kansas, attended the local public schools, and took poetry lessons at Washburn University (where all this time I was teaching law). Young moved from Topeka (eventually) to New York City, where he is now the director of Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, an affiliate of the New York Public Library.

One part of the book (On the Aitchison, Topeka & The Santa Fe) is devoted to poems about Topeka, teachers and classes at local public schools, sunflower, booty green, the ice storm when "The lines for power & speech/freeze, then stiffen & fall-/thrown back into dark."

Ice Storm—1984 is an archetypal poem that, in its micro details, quintessentially inheres the style, words, images, and music: the four elements that galvanize Young’s poems into quantum poetry (a point explained below).

The poem Brown is also riding the Kansas train, a poem about Brown v. Board of Education, the famous Supreme Court desegregation case involving Rev. Oliver Brown “who marched/into that principal’s office/ in Topeka to ask/Why can’t my daughter school here, just/steps from our house–.”

Each of the four parts of the book, each a cluster of long and short poems, is named after an actual (and representational) train. Each train is packed with sad and joyous moments and storied passengers, some unfamiliar to the readers: part one is the A train in New York City, part two is the Santa Fe Rail, part three is the Night Train, and part four is The Crescent Limited, a train that runs (away) from the South to the North, transporting Young’s style, words, images, and music from his parental roots in New Orleans to Schomburg Center at Malcolm X Boulevard in Harlem.

Just as quantum physics is the study of subatomic universe in which particles are entangled in superposition, sharing information, existing in several states at once, quantum poetry is the study of micro-experiences, unique but entangled, sharing space, “in a church basement like ours/where nursing mothers & children/not ready to sit still.”

The Brown poems fit the bill of quantum poetry.

For example, the Brown poems expose racism in small particles, micro-gestures, micro verses, micro images—while attending history classes, hanging by the rim, playing baseball with bases loaded, “remembering to breathe. Reds and blues, Kenny & I, party and after-party, humble pie & crow, shirts & skins,” all poetic pairs used in poems are poised in a state of being and becoming, “one dressed as the other.” They are simultaneously sharing the nitty-gritty poetic superposition, just as “We were black then, not yet/African American, so we danced.”

Foods and the love of food leaven the poems, a persistent theme in Young’s poetry. Food is shared, right and left. Popcorn, the grits, the jelly, juice, the beef thawing in the freezer as the ice storm denies electricity, everything is shared. Here and there, however, the love of food takes on playful selfishness: if “anyone asked/to share I’d hock/into my sandwiches/put the halves back/ together, then swallow//them slow” (two // denote double line-spaces that the author uses to augment the pause between the verses).

Young presents the black folks (turning into African Americans) as an artistic community “trapped outside in ice.” Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali, Reggie Jackson, Arthur Ash, each carrying his own pull, and black singers and artists visit various poems to remind the readers that the name-looting slavery, rugged segregation, and callous discrimination could not incinerate the artistic excellence of the black soul.

Walking away from the racist typecasts, the black folks, men, and women, well-known and unknown, inhabiting the Brown poems are smart, handsome, peaceful, enjoying the warmth of the family, with parents, single parents, uncles, Great Aunts, and the sweetheart, “less alone, her beauty and scent, /her buzzed head numbing your arm.”

Poems are musical. Music, through instruments and lyrics, jazz, hip-hop, blues, rap, you name it, has been perhaps the most precious Black gift to America. To prove this point, the poems summon the testimony of foreigners: “We black folks/invented all music.../say our Australian-/Pakistani-British/friends.”

By no means is this book a celebration of Black supremacism. Nor does the book paint whites as an incorrigible people predetermined to rubbish nonwhites. It is not a poetry written with acid borrowed from the Nation of Islam. In many ways, the Brown poems speak to folks of all hues, including whites. Nonetheless, Young is painfully aware of the fact “That hate mail you quit opening/kept coming, scrawled and sutured.”

Displaying craft and artistry, the Brown poems furnish a delight to ponder over poetic observations, images, and ideas that are joined, dis-joined, and rejoined through clever placement of words in succeeding verses and varying pauses.

Sometimes, the meaning meanders from line to line as the words that should come together are separated. Sometimes, the words seem to climb a spiral arbitrarily taking a break at unexpected places. Sometimes, the pause is longer than normal.

Consider, for example, “so I bring him bitters// which even the bartender/declares undrinkable. /David refuses// to say so, tries/choking down the pint/like pride.” Note the varying pauses. For example, the verse “David refuses” is separated by two line-spaces from the next verse “to say so.”

First, the reader believes that David refuses to drink bitters. Next, the reader learns that David refuses to agree with the bartender who declares the bitters to be undrinkable. “David refuses” acquires yet another meaning when David is choking on the bitters. Other interpretations are also in play. These multiple layers of meaning are generated by cleverly separating the words in successive verses.

There is one irritation that some readers might experience while reading the poems in which the conjunction “and” has been replaced by an ampersand “&” throughout the book. Researching the origin of the ampersand yields the fact that that once “&” was part of the English alphabet and the children memorized it as the 27th letter. In the Brown poems, Young restores the deleted letter & of the English alphabet. One wonders whether this restoration is a reminder of slavery that deleted many aspects of enslaved blacks.

Young is an accomplished prolific poet, fast becoming the darling of reviewers, poetry prizes outfits, and speaking circuits; he is a favorite invitee for reciting his poems. He has already published many books of poetry digging into American history and cultures. Brown, too, is American poetry.

With poems so promising, Young is destined to receive acclamation in the world, beyond racial and national walls that have been built or might be built in the future. However, he needs to absorb non-local consciousness to reach the next level of quantum poetry. Maybe, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, which caters to cultures of all the peoples of African descent, will furnish the opportunity to integrate local and non-local poetic consciousness.

L. Ali Khan is currently translating (interpreting) a number of ancient and contemporary Urdu and Punjabi poems, most famous in India and Pakistan, into English. He is aspiring to contribute toward intercultural understanding of diverse poetic traditions.

Spread the word