On Monday, the Ropes & Gray law firm, tasked with pursuing an independent investigation into the confluence of circumstances that allowed former USA Gymnastics and Michigan State University doctor Larry Nassar to sexually abuse more than 400 people over the course of several decades, released its long-awaited report, titled “The Constellation of Factors Underlying Larry Nassar’s Abuse of Athletes.”

That report, which was commissioned by the U.S. Olympic Committee back in February, features 256 damning pages about the culture, organizations, and individuals, that enabled Nassar’s crimes, famously perpetrated upon young women and girls under the guise of medical treatment.

While much of the information in the report was previously known, it is nevertheless staggering to read it all compiled in one place, accompanied by devastating new details that had heretofore remained undisclosed.

In fact, it’s hard to determine the most disturbing part of the report. Is it the revelation that Larry Nassar actually helped USA Gymnastics draft its rules concerning sexual misconduct, including “providing protections against false accusations?” Is it the intricate back-and-forth exchanges between USAG officials, lawyers, and Nassar himself about how to cover publicly for Nassar while he under investigation for sexual assault, even after he officially retired from the organization? Is it the fact that the FBI was tipped off about these cover-ups, and did absolutely nothing to stop it?

The answer, of course, is “all of the above.” Every one of these individual failures, each more heartbreakingly infuriating than the last, deserves sunlight and scrutiny.

But the overwhelming takeaway from the Ropes & Gray report is simply this: The USOC is broken beyond repair.

The organization was willing to overlook everything, as long as national governing bodies (NGBs) like the gymnastics program were bringing in new medals and money. And while some of the faces in the USOC have changed over the past year, and an extremely flawed “SafeSport” program has been implemented under the guise of athlete safety, nothing has really changed.

Nor is it likely to. As the report clearly shows, USOC took absolutely no action to protect athletes from Nassar after it found out about the allegations of sexual abuse. Those involved compounded these inactions by repeatedly lying about them, as recently as this past summer. And all of this was made possible by a system that put profit over people, a system that is still very much intact today.

Former USOC president lied to investigators

In mid-June of 2015, a USAG official was first notified about allegations of sexual abuse against Nassar by the private coach of a national team member. Over the next few weeks, USAG hired a private investigator to look into the allegations, and a handful of additional victims emerged. Toward the end of July, the private investigator told the USAG that there seemed to be validity to the allegations, and USAG decided to report Nassar to the FBI.

According to the Ropes & Gray report, then-president of USAG, Steve Penny, didn’t notify the USOC about the allegations against Nassar about six weeks after USAG was first notified of allegations of abuse, and after USAG had already decided to report the case to the FBI.

On the morning of July 25, 2015, Penny spoke with Alan Ashley, the USOC chief of sport performance, to alert him to a safe sport issue, and ask to set up a call with Scott Blackmun, then the CEO of the USOC. During this call, Penny informed Blackmun that national team gymnasts had expressed discomfort with medical treatments they had received from USAG’s national team doctor. Penny did not offer the identities of the doctor or the survivors, though he did ask Blackmun if Rick Adams, the Chief of Sport Operations and Paralympics for the USOC, could come to Indianapolis and assist the USAG in its reporting of the matter.

Blackmun and the USOC denied that request.

During his interview with Ropes & Gray — which spanned two days in July and August 2018 — Blackmun said that on this phone call, he confirmed with Penny that USAG had taken steps to prevent said national team doctor (Nassar) from having continued access to gymnasts, and that Penny confirmed that the doctor would not treat anyone at USAG going forward. Blackmun also said, according to the report, that “he believed he would have shared the athlete allegations and the referral to law enforcement with Larry Probst, Chair of the USOC Board of Directors.”

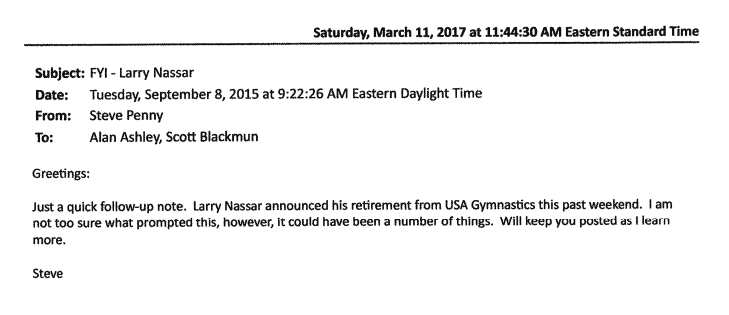

The next time Penny contacted the USOC about this, it was on September 8, 2015, when Penny sent an e-mail to Blackmun and Ashley notifying them of Nassar’s retirement. (Penny lies in this missive, claiming to be “not too sure what prompted this,” even though Penny and USAG had already told Nassar he was under investigation for sexual abuse. Nassar publicly portrayed his departure from USAG as a retirement by choice, and everyone — USAG, USOC, and the FBI — allowed that lie to stand.)

Ashley told independent investigators that he did not remember receiving that email, and that he would not have concluded that this note about Nassar was related to the conversation he had with Penny earlier in the summer about a national team doctor, even though Nassar was the national team doctor for USA Gymnastics.

Blackmun told investigators that he did not specifically recall this e-mail. Nevertheless, he attested to having made the connection anyway, which supposedly prompted him to call a meeting with other USOC officials “to talk about making sure we do the right follow-up on our side” because he “wanted to make sure that we were doing everything that we should be doing in response and that our response was appropriate.” Blackmun told investigators that the meeting likely included Adams and an in-house counsel, and possibly both Mark McCreary, Chief Administrative Officer at USAG, as well as Malia Arrington, then-Director of Ethics and SafeSport.

He told investigators that after this meeting, Adams was going to take charge to make sure the USOC stayed on top of it.

“That was my point of view: what else should we be doing, if anything, and have we been able to confirm that USAG did in fact report this? That was it,” Blackmun said.

The USOC actually did nothing at all to protect athletes from Nassar

The report doesn’t use such language, but there seems to be little doubt that Blackmun and Ashley are both full of shit.

After detailing all of the lies that Blackmun told investigators, Ropes & Gray lay down the gauntlet, letting it be known that in the course of their investigation — which included more than 100 interviews, including more than 60 current and former employees of USOC and USAG, and a review of well over 1.3 million documents — they found no evidence that Blackmun ever convened an internal meeting about Nassar. Similarly, they found no evidence to lend credence to the notion that he or Ashley ever told any other individual at USOC that Nassar was under investigation by the FBI for sexual misconduct stemming from allegations that he had sexually abused minor Olympic athletes at a USOC training center.

It can be a real problem when your memory constructs an alternate reality in which you’re not responsible for covering up for a sexual abuser and enabling him to abuse dozens of other girls and women. And so, when he was confronted with the results of the investigation, Blackmun quickly retracted his claims.

“After the Independent Investigators notified Mr. Blackmun, through counsel, of the lack of corroborating evidence for the internal review and asked for an explanation, Mr. Blackmun informed the Independent Investigators, through counsel, that he was mistaken in his recollection about having undertaken such an effort,” the report says.

The report does, however, detail all of the things that the USOC didn’t do — and the list is a doozy.

After Blackmun and Ashley found out that members of the U.S. gymnastics national team felt that they were being sexually abused by a national team doctor, and that the FBI was investigating the case, they took absolutely zero steps towards ensuring the safety of other athletes.

The USOC did not, in fact, take any steps after receiving notice of the allegations from Mr. Penny to assess whether Nassar had treated athletes at USOC facilities or while on the medical staff at the Olympic Games or other USOC events. Nor did the USOC undertake any follow up to ensure the safety of athletes, such as confirming that USAG had in fact referred the allegations of abuse to law enforcement or that USAG had implemented effective measures to prevent Nassar from having any further contact with athletes. Similarly, the organization did not take any steps to ensure that Nassar would be denied access to athletes at USOC training facilities or at USOC-sponsored events. Nor did it make any independent report to any child protection authority.

Additionally, Blackmun and Ashley kept everyone at the USOC — including those who specialized in athlete safety — in the dark. If the Indianapolis Star hadn’t published its initial report on Nassar in September 2016, there is no telling how long that silence would have persisted.

At no point did Mr. Blackmun or Mr. Ashley provide USOC personnel, including those with relevant expertise in SafeSport matters, with any of the information from Mr. Penny regarding the alleged sexual misconduct or the referral to law enforcement. By way of example, Malia Arrington, then USOC’s Director of Ethics and SafeSport, did not learn of the sexual misconduct allegations, or more specifically that a USAG team doctor was alleged to have sexually abused one or more athletes, until the allegations were made public in the Indianapolis Star approximately one year later. Nor did Mr. Blackmun notify the USOC’s Board of Directors, notwithstanding that SafeSport issues were a continuing subject of discussion at board meetings during this time. According to witness interviews, USOC board members remained unaware of the allegations and the potential ongoing threat to athletes until the Indianapolis Star published its account of Nassar’s abuse in September 2016.

Blackmun voluntarily stepped down as CEO of the USOC in February, three days after the conclusion of the Pyeongchang Winter Olympics. At the time, he cited health complications due to prostate cancer as the proximate cause of his decision to retire. Throughout it all, the entire USOC board continued to support him, even as the Nassar scandal — and further information about his inaction — continued to unfold in public.

“He has served the USOC with distinction,” Probst said of Blackmun in the weeks before his retirement. “We think that he did what he was supposed to do and did the right thing at every turn.”

Blackmun was invited to testify before the Senate in June at a hearing about sexual abuse in Olympic sports, but declined due to health reasons.

Ashley worked for the USOC up until Monday, after the report was released.

The entire USOC system is culpable here

The key to remember here is that all of this goes well beyond one sexual abuser (Nassar), or even one sport (gymnastics). This is a problem that the USOC has allowed to fester and grow for decades, because their priority has been the inextricably linked bedfellows of medals and money, at the expense of their athlete’s well being.

Over the years, the USOC has developed a streamlined, top-down management structure which has greatly diminished any opportunity for athletes to register complains about the organization or otherwise participate in its governance. This wasn’t always the case: Former USOC employees told investigators that during the 1980s, athletes had a “huge voice” in the organization. It was only after the governing body was restructured, that it became more of a “hierarchical business relationship” that largely excluded their input.

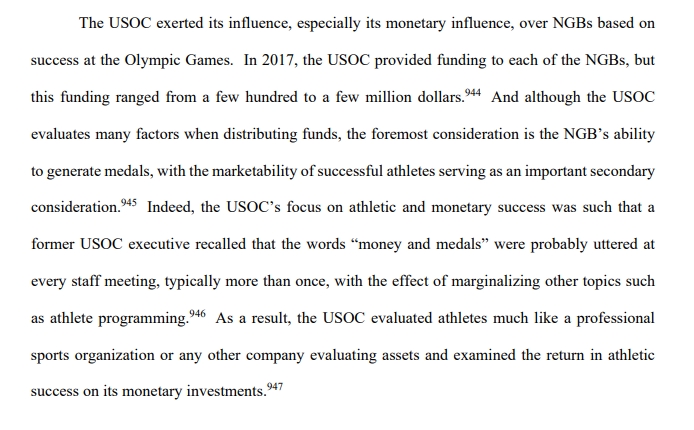

Naturally, at the heart of that business relationship was money. Congress provides the USOC authority over Olympic and amateur sports through the Ted Stevens Act, and gives it the ability to raise money both through trademarks — such as the famous five Olympic rings — and the commodification of individual athletes. In other words, Congress doesn’t directly fund the USOC or the governing bodies, it just gives the USOC the authority to raise money and dispense it to the NGBs as it sees fit. In 2014 and 2016, the USOC generated over $275 million and $350 million, respectively.

The report’s conclusion makes no mistake about the arrangement: “The foremost consideration is the NGB’s ability to generate medals, with the marketability of successful athletes serving as an important secondary consideration.”

When Blackmun took over as USOC CEO in 2010, one of the first things he implemented was a hands-off approach towards the NGBs, one in which the USOC provided them with resources, but no accompanying oversight. In the short term, that improved the often contentious relationships that existed between the USOC and its constellation of NGBs. In the long term, however, it had dire consequences that directly impacted the Nassar case in two crucial ways.

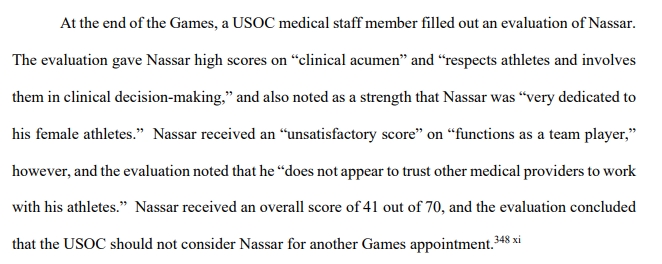

First of all, while USOC medical staff members filled out evaluations of doctors at the Olympics, the USOC seemed to give those evaluations little to no weight, completely deferring to the NGB’s choice of medical providers for the Games.

In 2012, the USOC appointed Dr. Bill Moreau as the new Managing Director of Sports Medicine. At the Olympics, Moreau was alarmed by Nassar’s practice of treating gymnasts outside of the USOC’s central medical area. According to the report, Moreau told Nassar that he “shouldn’t take care of athletes alone” because witnesses would be crucial to have in the event of a dispute with an athlete. Nassar refused to change his methods, claiming that USAG national team coordinator Marta Karolyi required the gymnasts to be treated separately from other athletes.

Then, at the end of the 2012 Games, a USOC medical staff member filled out an evaluation of Nassar, which concluded that the USOC should not consider Nassar as a doctor for future Olympics.

However, Nassar was scheduled to be a doctor at the Rio Olympics before his abrupt retirement, and Moreau told investigators that the USOC always erred on the side of keeping the NGB and its athletes happy during the Olympics. It seems that attitude was particularly acute when it came to successful, money-making NGBs like USAG.

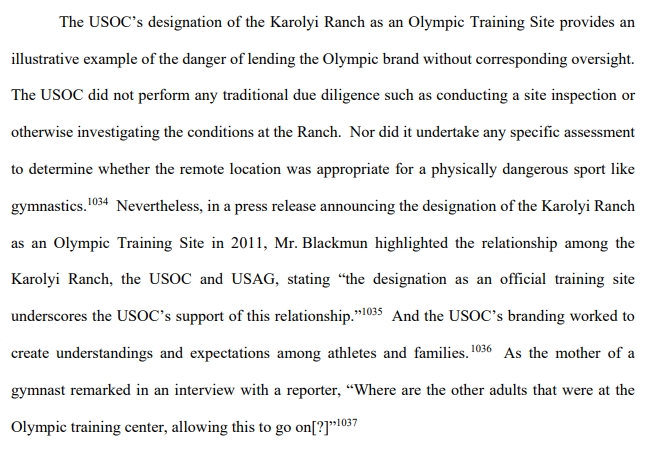

There was a second consequence of the USOC’s lack of oversight: The USOC conducts almost no review of facilities that it grants as an Olympic Training Site, except to make sure that the site is properly using the USOC brand. That meant that the Karolyi Ranch, which was designated as an Olympic training site in 2011, was held to practically zero standards by the USOC, despite the fact that it carried the USOC’s name.

Dozens upon dozens of gymnasts were abused by Nassar at the Karolyi Ranch. Moreover, it turns out that Nassar didn’t even have a valid medical license in Texas, where the ranch was located.

The Karolyi Ranch was not required to meet even the minimum USOC SafeSport standards — standards put in place to protect athletes from sexual abuse — until 2017, when Nassar was already behind bars.

There’s no redeeming the USOC in its current form

The USOC responded to the Ropes & Gray report by firing Ashley, expressing shock, and claiming that it was already on the path towards a better tomorrow.

“This year, the USOC has already taken important actions to strengthen athlete safeguards and help the USOC be more effective in our mission to empower and support athletes,” said USOC CEO Sarah Hirshland, who joined the USOC in August 2018. “Sexual abuse, harassment and discrimination have no place in the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic community, and it’s on all of us – member organizations, institutions and individuals alike – to foster a healthy culture for competitive excellence. We will use the findings from Ropes & Gray’s independent investigation to do everything possible to prevent something similar from happening in the future.”

The organization certainly took an important step last month, when it began the process to decertify USA Gymnastics.

But while the rot runs deep, it starts at the top.

USAG is not the only organization that has had huge sexual abuse scandals under USOC’s not-interested-in-oversight-at-all watch. USA Swimming, USA Diving, USA Volleyball, and USA Taekwondo, among others, have all been mired with predatory coaches and trainers who were not held accountable.

In order for any of this to truly change, the current funding model for Olympic sports has to be reinvented. The USOC, in its current form, is run like a for-profit organization, and so the only way that NGBs and athletes are of use to the USOC is if they’re earning medals and helping generate money. Such a structure incentivises everyone to look the other way, as long as the medal-count tallies are high. Moreover, it encourages athletes to be silent, and keep any complaints to themselves.

Funding and support cannot be directly tied to medals and publicity. That’s a recipe for disaster and corruption.

Unfortunately, it’s also been a recipe for success. The U.S. Olympic teams are as successful as they’ve ever been, and the Games continue to be a cash cow for sponsors, NGBs, television broadcasters, and the USOC alike. Making changes to this winning formula is scary, and it’s not surprising that there’s resistance to making fundamental reforms.

Ultimately, its Congress — the body that bestows this authority and power upon the wayward USOC — that is going to have to force these much needed changes upon the organization. That means that pressure to reform is going to have to come from the a willing public as well — because in order for a new, safer system to be implemented, the biennial priority on high medal counts might have to take a step backwards.

As it stands, however, if there’s one thing this devastating report elucidates, it’s that the United States Olympic Committee’s status quo is not worthy of our continued cheering.

[Lindsay Gibbs is a sports reporter at ThinkProgress.]

Spread the word