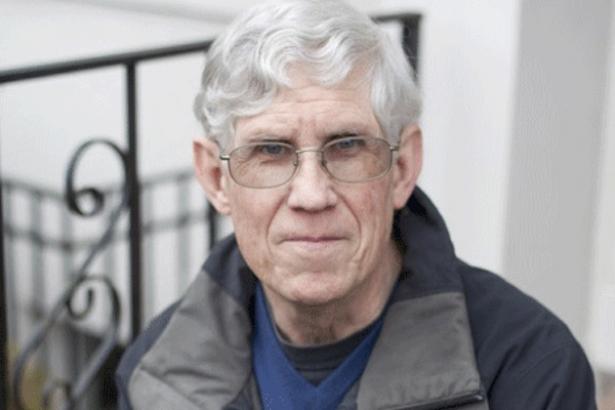

Carl Abbott is an American historian and urbanist, specialising in the related fields of urban history, western American history, urban planning, and science fiction, and is a frequent speaker to local community groups.

Why did you choose history as your career?

I’ll attribute it to Scrooge McDuck. In the early and middle fifties, writer/artist Carl Barks created a series of classic Donald Duck and Scrooge McDuck comic books that often sent Donald, Scrooge, and the nephews chasing a historical myth or artifact. Along with the story, you could learn about Coronado’s search for Cibola, Vikings in Labrador, and Walter Raleigh’s expedition up the Orinoco in search of El Dorado. There was plenty of fantasy in the comics, but also tantalizing historical nuggets that led naturally to the Landmark Books, a series of history books for kids that my dad brought home from the library, and to reading real accounts of archeology. At one point I thought it would be great to be an archeologist, until I figured that they spent their time roughing it in sweltering jungles and blazing deserts and decided that reading and writing about the past in reasonably comfortable libraries might be more pleasant.

What was your favorite historic site trip? Why?

Chaco Canyon: There is nothing else like it to remind 21st century Americans about the depth and complexity of our continental history. Tour the grand houses on the canyon floor and then climb to the rim to imagine the trade routes that radiated from what was essentially a metropolitan complex. Hadrian’s Wall and Housesteads Fort provide something of the same imaginative transport into a different past, especially when visited in proper English weather with dark skies, wind, and rain showers. For those interested, Gillian Bradshaw, Island of Ghosts, is a very well done novel that is set at the wall in the 2nd century and speaks to Britain’s multiracial past.

If you’d asked me when I was six years old, it would have been Castillo de San Marcos at St. Augustine (a fort! with high stone walls!! and cannon!!!).

If you could have dinner with any three historians (dead or alive), who would you choose and why?

Charles Beard, Frederick Jackson Turner, and Carl Becker, foundational voices for United States history as a comprehensive scholarly endeavor embracing social, economic, and intellectual history. I would be eager for their opinions on our current ideas about historical epistemology and on the vastly expanded range of our understanding of past lives and peoples. If I wanted to be provocative, I might add or substitute that historical gossip monger Suetonius to see what juicy stories he didn’t dare put into his Lives, although I’d have to brush up on my high school Latin.

What books are you reading now?

I just finished service on an OAH book prize committee that received ninety submissions, so I feel extremely caught up on certain aspects of U.S. history. I recommend Beth Lew-Williams, The Chinese Must Go, Susan Sleeper-Smith, Indigenous Prosperity and American Conquest, and Julian Lim, Porous Borders. On the nonacademic side, I have just finished Margaret Drabble, The Dark Flood Rises, a deeply humane novel about the ways that we confront aging and death (it is not depressing).

What is your favorite history book?

William H. McNeill’s The Rise of the West has been dated by decades of global history scholarship from different regions and postcolonial perspectives but it was eye-opening in the mid-1960s for someone who had just been through the Western Civ approach to history. I had the stimulating experience of taking a course on the history of the Balkans from McNeill at the University of Chicago and hearing about his approach to teaching (read a lot of books, close them, talk about what you’ve learned) and to writing (read, take minimal notes, close the books, organize your thoughts, write). I’ve only been able to follow this very challenging sequence a couple times, but I’ve really liked the results. After you revisit The Rise of the West, read Kim Stanley Robinson’s alternative history novel Years of Rice and Salt, which imagines the course of world history if 99.9% of Europeans had died in the plagues of the 1300s.

What is your favorite library and bookstore when looking for history books?

Living in Portland, I have easy access to Powell’s City of Books, a great independent bookstore that’s chock full of interesting finds on its multiple color-coded levels. When looking to order a book online, consider visiting Powells.com rather than defaulting to the first letter of the alphabet.

As a researcher, I’ve been privileged to work in both the Newberry Library and the Huntington Library, two treasure houses for scholars. When you walk out of the Newberry you have all the vibrancy of Chicago to enjoy; when you take a break at the Huntington you can wander its gardens. Chicago may be urbs in horto but that chunk of San Marino is bibliotheca in horto. Because I might have ended up a historical geographer if I had not attended a very small college with no geography courses, let’s highlight the Newberry’s map collection and the Geography and Map Division at the Library of Congress.

Do you own any rare history or collectible books? Do you collect artifacts related to history?

I am not much of a collector. The old books in our house are Quaker journals and sermons from the 18th and 19th century, passed down in my wife’s family for several generations, which support her writing and teaching on the Society of Friends.

Which history museums are your favorites? Why?

There’s no way I could show my face around here if I didn’t single out the Oregon Historical Society, where I’ve advised on numerous projects and whose library I’ve used for 40 years. Like all state historical museums, it has been responding to the need to broaden and deepen the “white guys” narrative with very good intent and generally successful results. I serve on a citizen committee to monitor a local tax levy that supports the Society, so I do get an inside view of their efforts to do a lot without enough money. We also need to acknowledge the valuable work of county historical societies and museums all over the country, where public historians are doing their best to add richness and nuance to the old pioneer stories—so a shout-out to the Deschutes County Historical Society (Bend, OR) and Crook County Historical Society (Prineville, OR) for recently inviting me to give talks and providing the impetus for weekends in sunny central Oregon. On big museum scene, I learn new things on each visit to the National Museum of the American Indian.

Which historical time period is your favorite?

The right question can make any period interesting, but what originally engaged me as a graduate student were the early decades of the 19th century when the territory northwest of the Ohio River was being transferred and transformed from Indian to white occupation and development. This is the area where I grew up and where my family has roots to the 1820s, and I wanted to understand how it had changed with the Miami and Erie Canal, early railroads, and industrialization that would create the technological infrastructure that produced the Wright brothers.

What would be your advice for history majors looking to make history as a career?

Historians should make friends with geographers and other social scientists and take courses in policy research methods. Much discussion of non-academic careers for historians focuses on closely related areas like museums, archives, and historic preservation. Historians with social science and policy research skills have a wider range of options in government and think tanks jobs that should not automatically be ceded to economists.

Who was your favorite history teacher?

The entire History Department at Swarthmore College when I was there in the 1960s—Robert Bannister, James A. Field, Jr., Paul Beik, and Lawrence Lafore. Specializing in U.S., French, and British history, they had distinct personalities but all nurtured a love of critical inquiry. In addition, I have a soft spot for the Chicago historian Bessie Louise Pierce. She was long retired from the University of Chicago by my time there, but attended my dissertation defense and told me quite firmly not let myself be pushed around by my committee (Richard Wade, Robert Fogel, Neil Harris).

Why is it essential to save history and libraries?

It’s a truism that we are all our own historians, a point made long ago by Carl Becker and recently reaffirmed by Edward Ayers. We understand our lives and world by the stories we tell about how we—and things in general—got to be as they are. It is the job of folks who are paid to study, write, and talk about history to help people tell accurate and inclusive stories that can be the foundation for a progressive and inclusive nation. That’s as important in Britain, India, Mexico, and every other country as it is in the United States.

The last couple decades have been a good time for public libraries. Cities all over the world have been investing in library systems that are true community learning centers as well as book-lenders. The list of cities that have found it worthwhile to build new, architecturally exciting downtown libraries is long. Calgary is the most recent entry, but there’s Perth in Australia, Birmingham in the UK, Guangzhou, Amsterdam, San Diego, Seattle, Salt Lake City, Denver, Minneapolis, and Chicago (which helped to kick off this new wave). It is quite exciting for someone who grew up on trips of exploration to the downtown library in Dayton, Ohio, and it holds promise for civic life. Academic historians understandably focus on university and research libraries, but public libraries nourish our audience.

Do you have a new book coming out?

I have two shorter books in process for series aimed to introduce topics to general readers. City Planning: A Very Short Introduction is for an Oxford University Press series. Quakerism: The Basics, which I am writing with my wife, is for a Routledge series. I am trying to build up steam for a book on the ways in which speculative fiction uses and abuses history (galactic empires modeled on Rome, alternative history, etc.) but it is a long way from daylight.

Author/Interviewee Carl Abbott is an American historian and urbanist, specialising in the related fields of urban history, western American history, urban planning, and science fiction, and is a frequent speaker to local community groups.

[Interviewer Tiffany April Griffin is a features intern at History News Network.]

Information on History News Network, including on joining its mailing list, is available HERE.

Spread the word